“Architecture is the testimony of the time it is set in…”

Lebanese architect, Karim Nader practices design fervently and conscientiously, believing that architecture moves through nature as much as nature moves through architecture. By Joana Lazarova

“If there is more appreciation for where we are, there might be a reduction of the amount of construction – there is really no need for so much construction. We should try to always ask ourselves whether an intervention is necessary before we intervene, and the choice for the architect is to be involved or not in certain projects, and to be motivated by better intentions.”

Karim Nader

Founder of Karim Nader Studio

Much of Karim Nader’s work has an intimate relationship with the landscape they inhabit. His work is embedded sensitively on the land he works on and is inspired by the landscapes that created them. “When I talk about landscape, I talk about nature and climate, colour and texture – the natural landscape in its wider context, but I also talk about the socio-historical landscape that makes up a certain place. As for the site, really at the centre of the whole architectural act, the nature of it needs to be felt historically, socially and geographically. A site is a natural condition in becoming, it is also a historical condition in evolution,” he says.

In a deeply engaging telephonic conversation with Joana Lazarova, he touches on his projects as he expresses his critical views on parametricism that takes away the element of surprise in architecture, the restoration projects he has been involved with where he puts to use the art of ‘remembering forward’, the notion of light, the importance of public spaces and the cinematic dimension of architecture.

Reflecting on the global pandemic and the uncertainty of the times we are in, Karim says, “The past decades have been harsh, both on humans and certainly on the planet. The recent pandemic – a global issue, which everyone can relate to – is bringing the whole planet together and this is very powerful. To address emerging environmental and social challenges, we must operate on the scale of climatic and ecological contexts, and place communities and humans as priorities. What we need to learn is that we need to live on the scale of the planet and not at its expense.”

A project under construction, On the Rocks which is described by Karim as a multitude of grey volumes surmounted by a roof, that reiterate the elements of a house iconography. “It is as if nature has taken over, and in the numerous gaps where light seeps at varying angles, it is more of a garden folly that emerges this time,” he says. Photography by @Marwan Harmouche.

The project “On the rocks” appears to interlock with its environment physically and emotionally. Can you tell me about it?

The project “On the rocks” is very particular, because it’s a landscape with practically no vegetation, with big rocks all around the site and just a few trees and bushes and flowers that pop up occasionally. In this barren landscape, the sky is also grey for a very long time throughout the year. So, this greyness is reflected in the design of a project which is very low so that the building does not exceed the height of the tallest rocks surrounding the site. It’s a one-storey house with a big rectangular roof in black zinc, which alludes quite clearly to a man-made gesture. A rectangular, pure form alludes to the human mind, and then under it, a collection of boxes of different dimensions and heights that might look haphazard, an ‘organic chaos’ that hides in fact the logic of the programme. And finally, the texture of concrete as the chosen material, with its vertical planking, echoes the striation of the rocks, as well as their colour.

On the rocks: “The rooms are warm worlds, fully cladded in wood to create the needed double-wall without exceeding a contemporary standard of thickness.”

Is model making for you a device for uncovering specific aspects of the design?

Through models and such interventions, you don’t lose the human touch. I am critical of parametricism in architecture because what is at work here is exactly the opposite. The nature of intuition is exactly that: an answer spontaneously appears that contains, through a simple gesture, the sum of parts of all questions asked and even more, a poem in space. In less abstract words, one could say that we start by looking at what is measurable: site setbacks, building heights, material by-laws, etc. Once those limits are considered very factual and accepted – even embraced – the psychological dimension of the client and the site enter into the equation. When it comes to clients, it is more in the realm of feeling: sometimes a simple image they have shown, or in the case of a company, their brand image could be a trigger for a certain aesthetic, to quote or to subvert, but always sentimentally.

The human perception of a certain contextual condition is translated into a vision and this vision has a goal to disrupt perception, architecture is the art of producing surprises. If parametricism can predict certain aspects of the design, it is actually the opposite of what vision is about, the production of something unpredictable, and a successful architecture is supposed to take you by surprise and open up a new world that wasn’t there before, in the same way writing a novel does. It’s possible in a novel to create a whole world that has not yet ever existed. In the same way, through the arrangement of architecture, it is possible to create a certain spatial setup that will take you to a new place. Therefore, it is impossible to know it in advance, instead, you need to involve yourself in the search and research of designing, you should be an adventurer in designing, and open up to whatever is happening on the drawing board and from all these things, a vision will be born.

You’ve been working on several preservation projects in Lebanon that carry many complex layers of history. Can you speak about these interventions?

The restoration of La Tour a building of the 1940s is an intervention in subtlety, “nothing to do when a project is already masterful.,” says Karim., “A new layer of paint of barely reflective yellowish concrete finish to echo the yellow building metaphor this time around, gold balustrades with corten steel planters, chrome aluminum finish and a cantilevering crown pergola extension in gold wires and landscape at the top and eastern corners to smoothen the object in a layer of native vegetation.”

From Nineteen84 to Immeuble de l’Union and more recently La Tour, we have indeed been involved in preservation work since 2016. Beirut has this remarkable quality of a legible and complex multi-layering, which is also characteristic of all Lebanese culture, a civilization that has been there for millennia. For Immeuble de l’Union, currently under restoration, we sought to preserve a lot of the DNA of the building, a proto-modernist ‘whale’ on an island site next to one of the few public gardens in Beirut. But when a certain aspect needed to be changed, we sought to do it in a totally honest way, without reproducing past forms in any way. I like to talk about ‘reprise’ quite often, a term I borrowed from Kierkegaard and which is a sort of ‘remembering forward’. It protects art from the defeat of nostalgia and also the pitfalls of futuristic trends, which quickly become outdated. The project is also a rare opportunity to preserve something in a city that has been very obsessed with the destruction of its own history, mostly due to post-war greed in the absence of proper heritage laws. In both renovation projects, La Tour and Immeuble de l’Union, the vegetation is not decorative. It’s really an inherent layer that is added to those buildings to alter perception.

It seems as if you sculpt the buildings from their environment but you also succeed in bringing an added quality to it. For the Amchit residence and Tahan Villa, you explored the notion of light?

The light is a device of the change of nature and the nature of change. An architecture sensitive to light will also be changing a lot as the days and nights pass. The Amchit residence is very particular in the sense that it is almost a diaphragm of light with a structure that is very absolute, with columns that repeat, creating shadows moving in and out of the house as they interact with the movement of the sun. Many projects also take on a life of their own at night, like for example the Tahan villa, in which sunlight penetrates through the cracks of the stone, and then at night the artificial light from the inside projects outward from the building. Many people have asked what the material of the façade is because it never really looked like stone. It looks like fabric but it is stone, which is synonymous with solidity and weight, whereas in this case, it is synonymous with fragility and lightness.

The Tahan Villa is so positioned to optimise and enhance the view around while respecting the sloped nature of the terrain. Photography by Ieva Saudargaite

The Amchit Residence is conceived as a layering of decks. The beach house seeks to maximise its relationship with the sea through a visual and compositional celebration of the Mediterranean horizon. Photography by Ieva Saudargaite

In a sense, the work always aims to place itself at an intersection between an almost natural aggregation and the man-made?

Architecture is always a testimony of the time in which it was constructed. Architecture outlasts an individual’s lifetime, and from a human point of view, there are certain layers of humanity involved in the making of architecture. In the case of Immeuble de l’Union, there is the craftsmanship of the building in the ‘50s – a time where everything was practically handmade. We are of course attentive to craftsmen because they know how to build better than architects. There is the world of the idea of the architect and the constructive reality and the feedback you can get from builders. Then you have the human dimension of the client, which is the initiating point of the project, where a client comes by default with a certain vision, a certain aspiration and desire, whether it’s a private project or a developer, there is still a desire and a direction that the client would like to go in. And this is really where the big challenge lies: to try to absorb what the client is dreaming of without compromising what you consider to be a good idea, to come to a proposition of an architectural project that inspires the client to own this idea and adopt it, and for the architect to have a real opportunity for artistic expression. And later on, you have the users, and this is an interesting question to think about, this aspect of the architectural process, how you will be affecting their lives, how architecture is going to propose something that will be the framework of their lives, and how architecture can contribute to a certain awakening, to a certain awareness of being somewhere: the awareness of place, meaning architecture as placemaking, and the pleasure of being somewhere, so really the day-to-day living in a house, office, hotel, and how the architectural composition is going to affect users emotionally and even intellectually. Architecture can be like watching a film, and it talks to you as if you are the actor in this ongoing film.

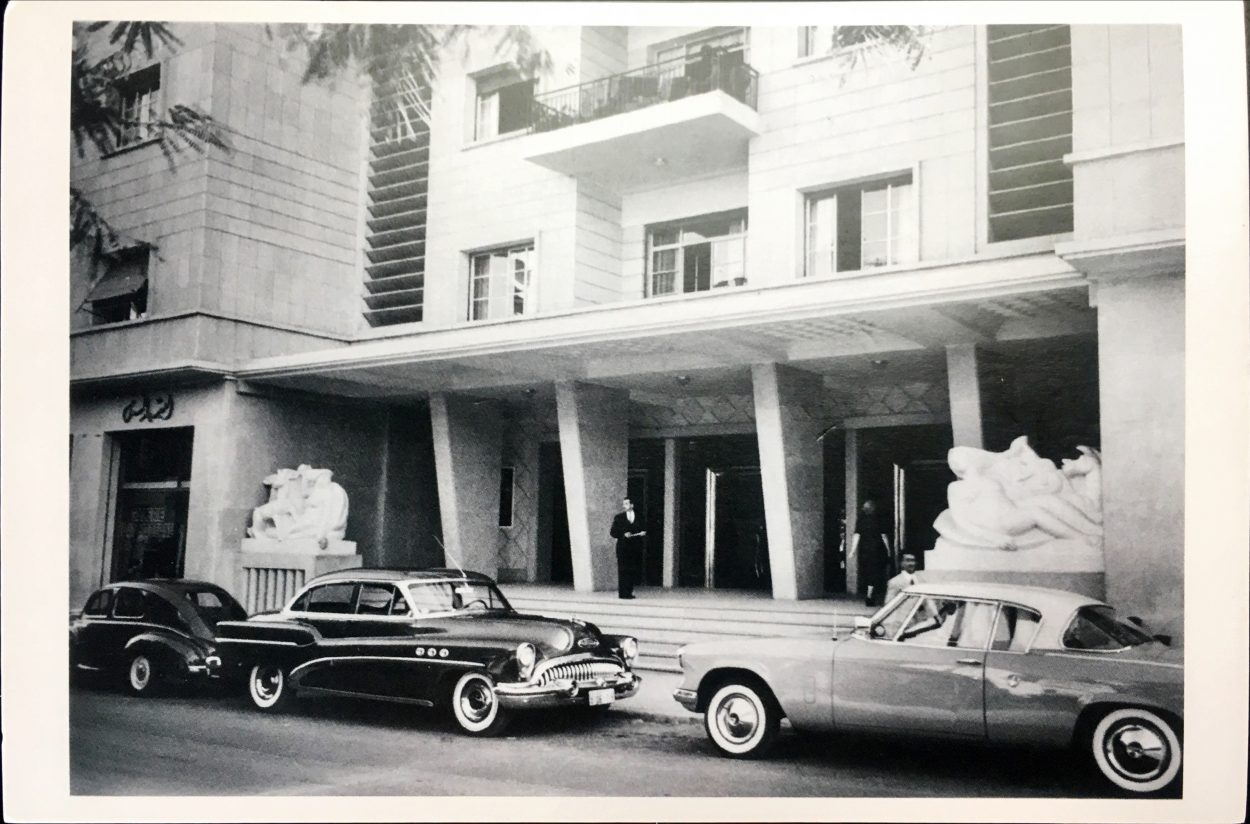

The 1952 Immeuble de l’ Union on Spears street. is grand, luxurious, and refined, that embodies the spirit of a golden era of Lebanon. Karim wishes the restoration to be an example of renovation without nostalgia through mixed-use re-programming. “We aspire to practice restraint, attempting to never overpower the original lines of the design, but we also need to know how to intervene when it is needed, to make the building safer, lighter and more user-friendly: an architectural intervention for enhanced legibility and even more beauty.” Photograph courtesy of Arab Center for Architecture

It was Gordon Matta-Clark who said that cinema and architecture are very much alike in the sense that they both create and express a desire and build a dream.

This is a big subject: Architecture and cinema, cinema and architecture. I am aware of the cinematic dimension of architecture and I design with this in mind. Why I am mentioning this is because architecture is never experienced from an axonometric view. It’s always experienced from one perspective at a time, one point of view at a time. If you start to walk from room A to room B, you are indeed creating a sequence of images, and if architecture is conscious of this movement, it is, therefore, possible to set the stage for all sort of surprises, illusions, framings, cuts, dissolves, and many other effects that belong to the cinematic language. So, many times during our projects, we mention cinematic vocabulary, because opacity, transparency, translucency, and sequences of space and circulation are all possible devices for reinforcing a cinematic experience.

There is something cinematic about these black and white images of the Centroplex project under construction.

We intentionally took these images in black and white, in order to reinforce the effect of light. After all, photography is the process of imprinting light onto film, or a sensor with digital photography. The aesthetic of a building under construction is very particular, because you have the skeleton of the space built, but it isn’t yet an enclosure. I have always been fascinated by a structure under construction, how light filters through the steel structures. In the coming week, they were going to clad the structure, and this experience was going to be lost forever, so we wanted to document it. It is also an opportunity to show the people involved in the construction: the welders, structural engineers, as they became the characters of this black and white film.

“I have always been fascinated by a structure under construction, how light filters through the steel structures,” says Karim, as he wanders through the construction site of Centroplex, a cineplex within the Centro Mall. Photography by Karim Nasser

There is also another aspect of black and white – the idea of reduction. The notion of reduction of the medium is something that has always interested me, and it has interested a lot of artists in the past – Michelangelo Antonioni, for example. If you take as an example Il Deserto Rosso* – it was his first film in colour, but colour had already come to the cinema many years before he decided to use colour. He said that he was not ready for colour. I found this amusing, but it also means that he had so much to say already with the gradient from black to white and that moving to colour should be a conscious choice, because suddenly, the palette explodes and gives you so many possibilities. And the title of the film, ll Deserto Rosso – the red desert has a colour in the title itself, which demonstrates that he was aware of colour, and, in fact, there is a scene in the hotel where we see everything painted in white, including the plants, and you notice that it is actually artificially white.

In some of your works, for example, the MY Municipality project, the creation of public space plays an important role in the concept. Can you speak about the notion of public space in architecture in Lebanon today?

In the case of the project My Municipality, the brief of the project had already called for preserving the existing pine trees as much as possible, therefore one of the obvious decisions was to divide the building into two parts, therefore reducing the amount of excavation and cutting of trees as much as possible. One part of the project echoes the institutional part of a municipality and the village architecture of Lebanon, and the second part is a celebration of public space – a program required for the project – a little souk and an outdoor platform, a theater and a cinema.

I would say public space is challenged in Lebanon, particularly in the city, where you have a lack of public space, especially in Beirut. This is happening because there is a certain fear in the public sphere due to long periods of uncertainty and insecurity, and public space is the place where people can basically gather to prepare for a revolution, therefore this was something that was very much repressed for a very long time. The last revolution, which began on October 17th, 2019 and which is still ongoing, has been a period when public space has been reclaimed and people have been back on the streets, claiming them back as a place for public expression.

Speaking of these uncertain times we live in, what in your opinion should we be more aware of when designing and building for future generations?

What message should we keep? The first dimension for me is gratitude for being alive on this planet that is our cradle. If there is more appreciation for where we are, there might be a reduction of the amount of construction – there is really no need for so much construction. We should try to always ask ourselves whether an intervention is necessary before we intervene, and the choice for the architect is to be involved or not in certain projects and to be motivated by better intentions.

A project under construction, The Glass House, where the architect has used modern technologies married with stones recycled from ruins of nearby houses, as vernacular tradition moves forward with the advent of new technologies and a globalized exposure to modernist international style. Photography by Marwan Harmouche

The Tehan Villa is designed as a massive volume, seemingly floating in the landscape clad with sliding stone panels that echo the texture of the rocks surrounding the house. Photography by Ieva Saudargaite

Many times we see architecture being consumed by capitalism. There are so many rules in the reality of development – how many floors, what the apartments should look like – and therefore there are very big limitations when it comes to architecture as an art form and very little space for expression. I think that architects should reclaim their role of also being designers of the programme, the designers of a certain vision of urbanity or development. Architects should be more involved from the beginning in the development, in the programming of it, in the social consequences of the building, as well as the historical consequences of the building. I don’t want to lecture nor do I want to be an activist, but maybe there should be a bit more humility in terms of building more necessary things rather than superficial speculation?

*Red Desert (Italian: Il deserto rosso) is a 1964 Italian film directed by Michelangelo Antonioni starring Monica Vitti and Richard Harris.

All Images Courtsey: Karim Nader Studio

Main Image: Photography by Marco Pinarelli

Portrait in black and white: photography by Marwan Harmouche

Phone interview with Joana Lazarova, 2020