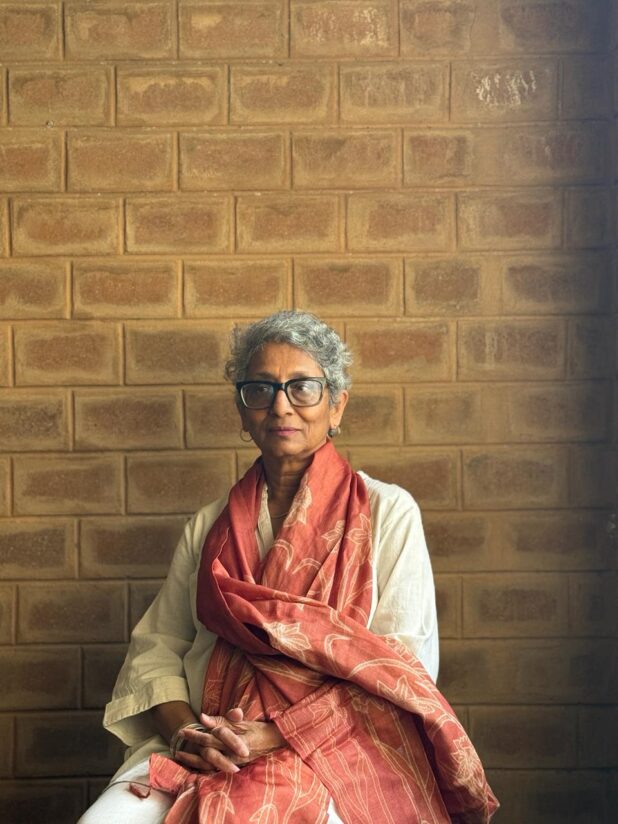

Chitra Vishwanath on the True Meaning of Modernity

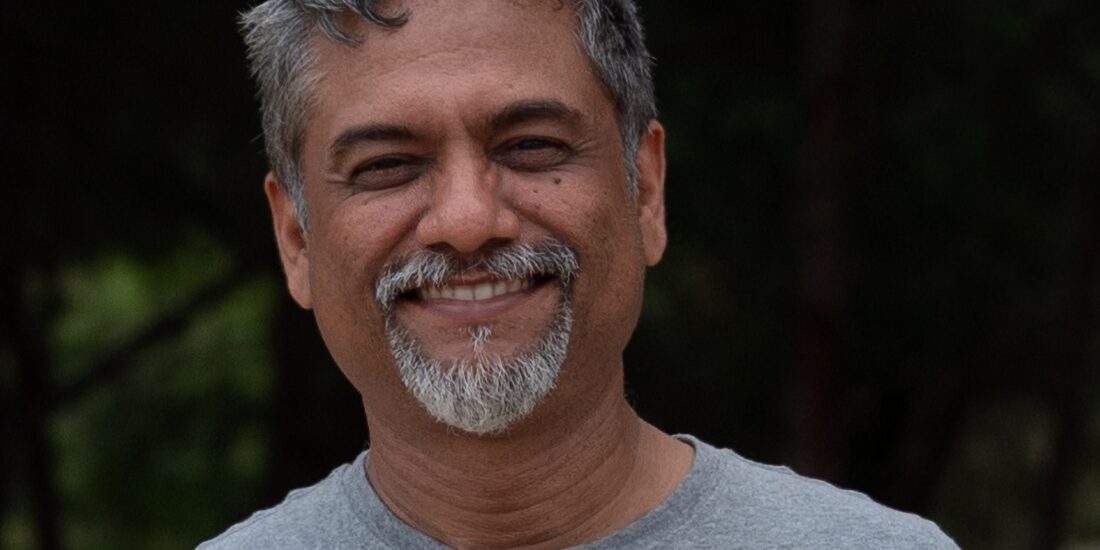

In an era where a splash of greenery on a facade is often mistaken for sustainability, Architect Chitra Vishwanath stands as a rigorous corrective. For her, true ecological practice is not an aesthetic choice but a series of informed decisions rooted in the “Everything” of a place, from the soil and the water table to the local climate. Along with her husband, Vishwanath S., she founded Biome, a multidisciplinary firm that focuses on ecological architecture and intelligent water and sanitation design. By Arya Nair

Chitra Vishwanath challenges the architectural industry’s obsession with industrial materials, boldly reclaiming the definition of what it means to be modern. While the world views concrete and steel as the pinnacle of progress, she reminds us that reinforced concrete is over 150 years old, making it an outdated relic that serves as a material and energy guzzler. To be truly modern, she argues that a building must be contemporary to its challenges, addressing climate change and the specific needs of the present moment.

For Vishwanath, building with earth is the most forward thinking technology available because it respects regional resources rather than depleting them. The work of Biome proves that a building should not be a parasite on its environment, but rather an anti-fragile addition to it. This philosophy is not confined to her blueprints; she practices sustainability as a lifestyle, embodying the principles she preaches, including the fact that she does not even own a car.

In the following interview, Chitra Vishwanath walks us through her transition from civil engineering to architecture and Biome’s research-led design process, and why the future of architecture must be dug from the ground beneath our feet.

SCALE: To begin, please walk us through your early life and the educational path that shaped your career.

Chitra Vishwanath: I was born in Benaras in 1962. I grew up in a creative and academic household because my father was a sculptor and a teacher at Banaras Hindu University. He eventually retired as the Dean of the Faculty of Visual Arts. Although we are Tamilians from Kerala, our family history is a blend of regions. My mother is from Cochin and my father is from Thiruvananthapuram. At home, we spoke a unique version of Tamil that is slightly different from the language spoken in Tamil Nadu.

My education took me across borders. When my father moved to Nigeria to set up a visual arts department, I chose to study civil engineering. After completing those studies, I returned to India to study architecture at CEPT in Ahmedabad. I finished my degree in December 1988.

In June 1990, I married Vishwanath, a fellow student I met at CEPT. We moved to Bangalore together. I have lived in Bangalore since 1989, which means I have spent more than half of my life in this city. It is the place I now call my true home town.

SCALE: What was the thought process behind shifting from civil engineering to architecture?

Chitra Vishwanath: This happened at a time when children did not know much about architecture. We are talking about forty years ago. It was actually my father who guided me because he was a sculptor. He understood the fields of architecture and design well and he was the one who encouraged me to become an architect.

He specifically wanted me to study in Ahmedabad at either NID or CEPT. He was always showing me pictures of those institutes and explaining the kind of work they were doing. Because of his influence, my only goal was to study architecture, but specifically in Ahmedabad. I think like any young person, I also had an aspiration to move away from my home town. It turned out to be a great decision because CEPT was one of the best institutes then and it remains so even now.

SCALE: What was the atmosphere like at CEPT during those years?

Chitra Vishwanath: We had a small class of just about twenty five students, so we all knew each other very well. The environment felt like a family. Since many of us had come from different places, we became more dependent on our peers than on our parents. At that time, we did not have tools like Google. We could not even book our own travel tickets easily.

The CEPT campus was a wonderful place to be during those years, especially for women. It was not just about the number of women on campus. It was about the fact that you could walk outside at two in the morning and feel completely comfortable. It is rare for a woman to feel that way in any city. Even back in 1982, we would cycle everywhere. We often left the school at one in the morning after finishing our work to go home and sleep, only to return by seven thirty. That sense of safety was incredibly liberating for women. It provided a level of freedom that we all hope for.

SCALE: Architecture is a broad field; what specifically drove you toward sustainability and ecological practice?

Chitra Vishwanath: My focus on ecological architecture comes from my personal background. It was not necessarily something I studied directly in Ahmedabad. Instead, Ahmedabad was a place where I developed my ideas, relationships, and a general method of learning. It taught me to be open to new knowledge and to apply it creatively. When you arrive in a city and a client brings you a problem, your role is to provide the solution.

During our first five years, we spent most of our time designing according to the ideas of Laurie Baker. His work focused on frugality and reducing costs, which was very relevant to the society and the economic situation at that time. In Bangalore, many people had heard of Laurie Baker, and some even viewed him as a legendary figure. However, I believe our approach was more pragmatic. We did not just copy his style; we adopted his core values while adapting them to suit the specific climate of Bangalore.

SCALE: How did you move from following a precedent like Baker to developing your own signature approach with earth and water?

Chitra Vishwanath: While we always followed the core values of Laurie Baker, we were not entirely happy with just following his specific construction methods. In 1995, we decided to build our own home. When we visited the site and saw the foundations of the neighboring buildings, we realized the soil was excellent. We decided to build a basement, which was something we had never done before. We knew that digging a basement would provide us with enough soil to build the rest of the house. We excavated the earth and used it as our primary material. We were thrilled to have found such a direct source for our building materials.

When we moved into the house, it rained. Vishwanath was at the site and noticed the massive amount of water flowing through the down-takes. He realized the potential of that volume and came up with the idea for rainwater harvesting. Our own house became a testing ground and a laboratory for these ideas, allowing us to experiment with both earth construction and water management.

SCALE: You mentioned that you discuss construction all the time. How did that practical and engineering-led focus change your relationship with clients?

Chitra Vishwanath: My perspective is shaped by the fact that I studied civil engineering and married into a family of civil engineers. Because of this, our conversations always centered on construction and the process of making things rather than just theoretical architecture.

This background allowed me to speak confidently to clients. I could tell them exactly how I would build their project and provide clear costs. Usually, architects were told not to discuss specific costs. They would often give a general price per square foot without taking much responsibility for the final budget. This lack of accountability was a major reason why many people avoided hiring architects.

I would provide an estimate and stay within five percent of that number. This transparency made it very easy for homemakers and working women to talk to me. I did not approach projects with a large ego. Instead, I focused on listening to their stories and designing based on their specific needs.

SCALE: You have turned the traditional idea of a house into a self sustaining system. How do you integrate elements like basements and water management into the very fabric of the building?

Chitra Vishwanath: We experimented with our own water filters and integrated those systems directly into the house. By including these elements, even a space like a bathroom becomes an important part of the ecological cycle. We also focus heavily on basements because they provide the material for the rest of the building. You cannot easily add a basement later, so it is important to plan for it from the start.

Basements are naturally comfortable spaces because they maintain a temperature of about twenty two degrees centigrade throughout the year. Even when it is fifteen degrees or thirty degrees outside, the basement remains steady. This makes it a beautiful and usable living space. Today, we even design basements that include gardens and wells, making them a central part of the home.

SCALE: Beyond harvesting rain, you have been a vocal advocate for managing waste. What is the Biome approach to wastewater?

Chitra Vishwanath: The most important question for us was what happens to the wastewater. The usual practice was to dig a pit in the road and let the waste go there, but that is not sustainable. We were concerned about what that would do to the groundwater. We researched and worked on various types of wastewater treatment systems, including decentralized systems known as DEWATS. We tested many of these different methods in our own house.

Most homeowners want a garden, and treated wastewater is actually the best water you can use for one. By treating the water, you protect the groundwater from contamination while maintaining a beautiful garden. This approach accomplishes three things at once. To us, the structure of a building is not just about a specific form or style. It is a living human ecosystem that works for both people and the planet.

SCALE: Sustainability is now a global trend. Do you still find yourself having to sell these ecological concepts to your clients?

Chitra Vishwanath: Most people come to us now because they have already seen our work. Interestingly, we were among the first architects in India to have a website. One of our clients was learning web design and used our firm as a project to practice her skills. Because of that early online presence and our reputation, we do not have to explain the basics very often. There is much more awareness today about how people should live and behave in relation to the environment.

We still negotiate with clients on certain details. We might suggest one material over another or ask them to reconsider a specific choice. However, the core elements are usually understood from the start. It is a given that we will build with earth, manage water, and treat waste. Once those big decisions are settled, the remaining choices are often about smaller details like color.

The industry is changing and many high quality, ecological materials are now available. We can use excellent lime plasters instead of traditional paints if a client does not want an exposed finish. We used to avoid paint entirely, but now we can simply use much less of it.

We also recognize that areas like kitchens and toilets have practical needs. These are spaces where clients might want to express their personal style or use specific tiles. Supporting those choices helps keep other professional skills alive, such as the work of talented tile layers. I also enjoy incorporating different fabrics into a building. Curtains and textiles bring a sense of change to a space. You can use different types for winter or summer, which adds a beautiful, temporary quality to the home.

SCALE: When you first walk onto a new site, what are you looking for? What is the Biome design process?

Chitra Vishwanath: I do not follow a traditional architectural approach. Instead, I use a concept I call “Everything Everyone Architecture”. When I first visit a site, I look at the “Everything”. This includes examining the soil and the water table to understand how people in the area access water. I study the sun paths and observe the existing biodiversity. Since modern buildings are often crowded together, I also focus on how to bring natural light and fresh air into the space.

Then I consider the “Everyone”. The “Everyone” is the client and the client’s brief. But if it’s not in Bangalore, you’re going to look around like: who constructs? And what do they know? What is the tacit knowledge that they know? What can I learn from them?

I look at the local community to see who is available to build and what specific skills they possess. I am always interested in the local knowledge and craftsmanship of the area. My goal is to see what I can learn from the people there and how we can work together to create the best possible structure.

SCALE: It sounds like every project is treated as a unique research case rather than a standard commission.

Chitra Vishwanath: Every project is indeed a piece of research. For example, at the Govardhan Eco Village, we had to conduct a full hydrogeological study. We spent a month discussing this with the clients until they were convinced of its importance. You should not create a master plan first and worry about the environment later. You must understand the land first to know where to place a building or where to dig a well.

This process involves integrating different types of knowledge into the design. You might have a well digger tell you that a certain area of soil is not suitable for digging, and you must learn from his expertise above all others. We negotiate these practical findings with our design team as we work. While we are sketching and discussing ideas, this technical background remains our backbone. The final design is simply the visible result of all the deep research we do behind the scenes.

SCALE: Can you give us an example of how you navigate that aesthetic negotiation with a client?

Chitra Vishwanath: Take our project in Bhopal for Eklavya as an example. We used grey bricks which do not look as polished as standard wire cut bricks. I had to convince the client to appreciate this look because it is far more natural. The future does not need a beautiful brick that has to be transported three hundred kilometers. If you really want a special material, use it sparingly. In that project, we used the more expensive brick on just one wall. It is like jewelry or lipstick. You do not want to cover yourself in it completely, but a little bit in the right place is fine.

This approach requires strong conviction. As architects, it is easy to be swayed by what we see in magazines or what others call beautiful. I find that kind of beauty very temporary. A building should provide solutions that are not fragile. In fact, they should be anti-fragile. A building should be a permaculture of solutions and an ecological addition to the site. It should never be a parasite on the environment.

SCALE: You have successfully applied these principles to homes. How do these methods scale up to larger, more complex projects?

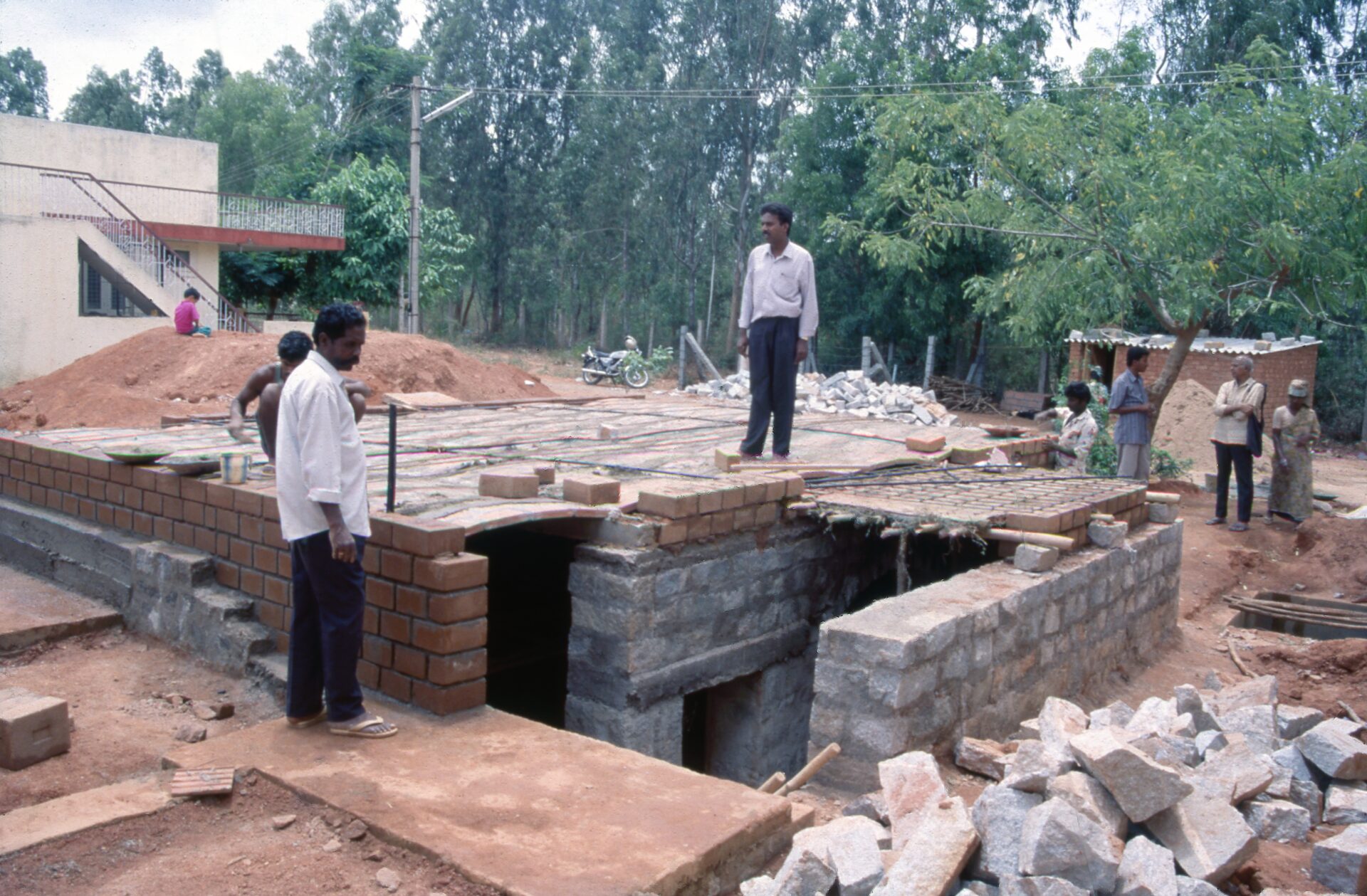

Chitra Vishwanath: Our process evolved as the scale of our work changed. We started with individual homes and rural projects where we focused on building with earth and managing water. Eventually, we took those same ideas and applied them to much larger sites, such as a project covering one hundred and twenty acres with three hundred thousand square feet of construction.

In another project, a resort in Tadoba called Waghoba, we faced a different challenge. The land would flood because the nearby road acted like a dam, yet the local well would go dry in the summer. We decided to create a large lake on the property. This provided the earth we needed for construction and created a new space for biodiversity. Now, birds and small animals frequent the area. Instead of just placing a building on the land, we created something that helps the surrounding environment. These interactions between water, wildlife, and construction are what interest us most, and we maintain this ethos no matter how large the project becomes.

SCALE: There is a common belief that we must build high-rise skyscrapers to accommodate urban density. Can your earth-based construction techniques work for that scale, or is there a lack of research there?

Chitra Vishwanath: This question comes from a mindset that accepts land is scarce and that we must build upward. However, we have to ask if this development model is actually right for the planet. When we focus on tall buildings, we often forget about the needs of children. We have to ask where they will find space to play.

I am always questioning the idea of density. People assume density means building taller, but you can also achieve density by building shorter structures closer together. Proponents of high-rises often say that building tall leaves more open land, but that is rarely true. In reality, that land is usually turned into massive concrete parking lots. It is no longer natural land; it is just more concrete.

SCALE: So you are essentially calling for a redefinition of what we call “modern” architecture?

Chitra Vishwanath: I believe we have to break away from the way we use certain words. We often call concrete and steel modern, but reinforced concrete is over one hundred and fifty years old. It is in no way modern. To be truly modern, a building must address climate change and serve the needs of the world right now. Modern buildings cannot be energy guzzlers or material guzzlers.

Using materials that deplete the environment is not a forward thinking approach. You should not be depleting the resources of one region just to build in another or destroying forests to produce steel simply because it looks modern. Building with earth is actually modern because the true definition of modern is being contemporary. Many architects use the word modern to describe something that is actually outdated.

Sai Krupa School, play of indoor and outdoor spaces

We need to rethink these terms. We are copying reinforced concrete structures across South Asia, but this makes no sense. This region will be one of the worst hit by climate change. We must develop a very different way of thinking that is specifically designed for our own region and its future.

SCALE: Mud is often dismissed in textbooks as a kacha or primitive material. What is the most common myth you hear from clients, and how do you correct that perception?

Chitra Vishwanath: It is easy for me to disprove that myth. First, I show people our own home, which is now over thirty years old. Nowadays, mud is no longer seen as an outdated or temporary material because the way we use it has evolved. We do not use pure mud. Instead, we mix it with quarry dust and stabilizers like lime, cement, or a blend of both.

We deal with two extremes: those who only want concrete and those who believe mud should stay in its most basic form. We choose a middle path. We use this material as a direct replacement for fired bricks and concrete blocks, which use far too much energy and cement. Instead, we use a material where fifty percent of the volume comes from right beneath your feet or from a nearby lake.

SCALE: Beyond the “green” appeal, how does this material perform structurally compared to the industrial standards we take for granted?

Chitra Vishwanath: No other material is as versatile as earth. Materials like stone or concrete are static; you cannot change them radically. However, I can modify an earth block to meet specific needs. If I need a block to act as a column or support a large beam, I can increase the cement stabilizer to ten percent. If it is only supporting a light roof, that content can be as low as two percent.

We provide scientific validation to our clients through rigorous testing in our own lab. We measure exactly how much load these blocks can take, ensuring the manufacturing process is precise in terms of volume and density. Interestingly, people accept concrete blocks or stones without question, but they scrutinize the earth constantly. In reality, our approach is infinitely more scientific than standard construction. This is the most contemporary way to build, far beyond basic RCC boxes.

SCALE: If the science is there, why is the awareness still so low? Is it a failure of education or the media?

Chitra Vishwanath: We are architects; our job is to keep working and building. But if you look at how someone like Laurie Baker became so widespread, it was because of visibility. People saw the work and journalists from traditional media like Malayala Manorama wrote impactful articles about it. We need that kind of reach again.

We need people to talk about architecture critically. Currently, architecture magazines are almost entirely uncritical and they rarely say anything of substance about a building. The conversation has become trite. We need deep, honest discussions on these ecological aspects to move forward. Ultimately, it is up to the media and the journalists to change the narrative.

SCALE: Do you see this moving from a niche architectural choice to a mainstream movement?

Chitra Vishwanath: This movement has already begun, but it is only thirty years old. Since reinforced concrete has had over one hundred and fifty years to establish itself, our approach will naturally take time to scale. For this to become mainstream, we need significant policy changes.

We need policies that prohibit throwing away soil excavated from a site and instead mandate its use. Imagine urban planning that designates specific spaces for making blocks on site. Once the construction is finished, those same spaces could be converted into areas for planting trees. This kind of systemic shift would turn individual architectural choices into a standard way of building.

SCALE: What is the final metric an architect should use before breaking ground?

Chitra Vishwanath: You have to consider the real impact of your material choices. If you build a steel structure here, you might be creating a hole in Bellary and destroying the habitat of the sloth bear. We use steel too, but we constantly ask where, why, and how much of it is truly necessary.

The final metric is a series of questions: Why, where, when, how, and who? We must ask these five questions every minute of the design process. An architect should never build without understanding the origin of their materials and the consequences of their use.

At Sai Kirupa Special School, a child rests within a curved brick alcove, showing how built form becomes part of everyday play and comfort. Photographed by Link Studio (Somusundaram C)

Biome’s practice serves as a vital foundation for the future of the built environment in South Asia. By dismantling the myth that “modern” must mean industrial and resource-heavy, she demonstrates that the most sophisticated solutions are often found in the very soil we stand upon. Her work is a reminder that architecture is not merely about creating a silhouette against the sky, but about nurturing a living, human ecosystem that manages its own waste, harvests its own water, and respects the limits of the planet.

Pictures Courtesy Biome