A Modern Landmark in Tehran by a Female Architect

Architect Habibeh Madjdabadi’s proposes a sweeping monument and public square in Tehran that refers to the idea of Persian historical squares.

A few months before the outbreak of the ongoing anti-regime revolution in Iran, the Municipality of Tehran launched a design competition for the Vali-Asr square, located on a homonymous avenue in the centre of the capital. Recently Vali-Asr had gained international notability after being mentioned in the viral revolutionary song Baraye.

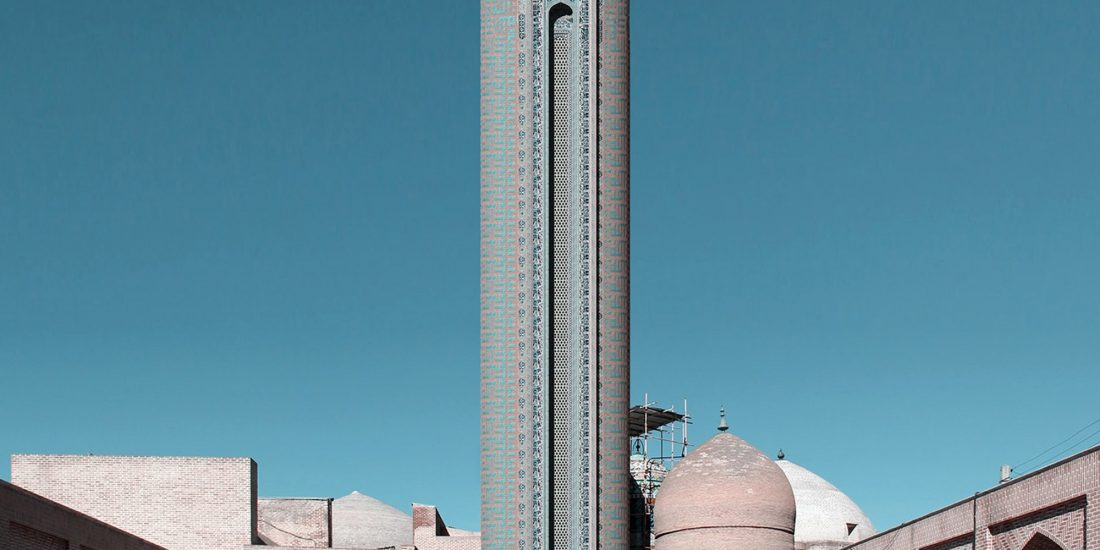

Habibeh Madjdabadi is from the younger generation of Iranian architects who is also an author, designer, and speaker. In 2002 she graduated with a Master’s degree in Architecture from Azad University of Tehran and started her professional career in 2003 by establishing her design studio in Tehran right after winning a first prize in the design competition, restoring a historical building (belonging to Zand dynasty) in Iran. One of her buildings has also been shortlisted for the Aga Khan Awards.

Habibeh Madjdabadi is from the younger generation of Iranian architects who is also an author, designer, and speaker. In 2002 she graduated with a Master’s degree in Architecture from Azad University of Tehran and started her professional career in 2003 by establishing her design studio in Tehran right after winning a first prize in the design competition, restoring a historical building (belonging to Zand dynasty) in Iran. One of her buildings has also been shortlisted for the Aga Khan Awards.

Madjdabadi’s proposal for the central square is an integral and organic solution at different scales. The project aims to redefine the concept of the existing square and give it a new connotation that refers to the idea of the Persian historical squares. Two projects were selected as winners for this competition, this proposal by Madjdabadi is one of the winning projects.

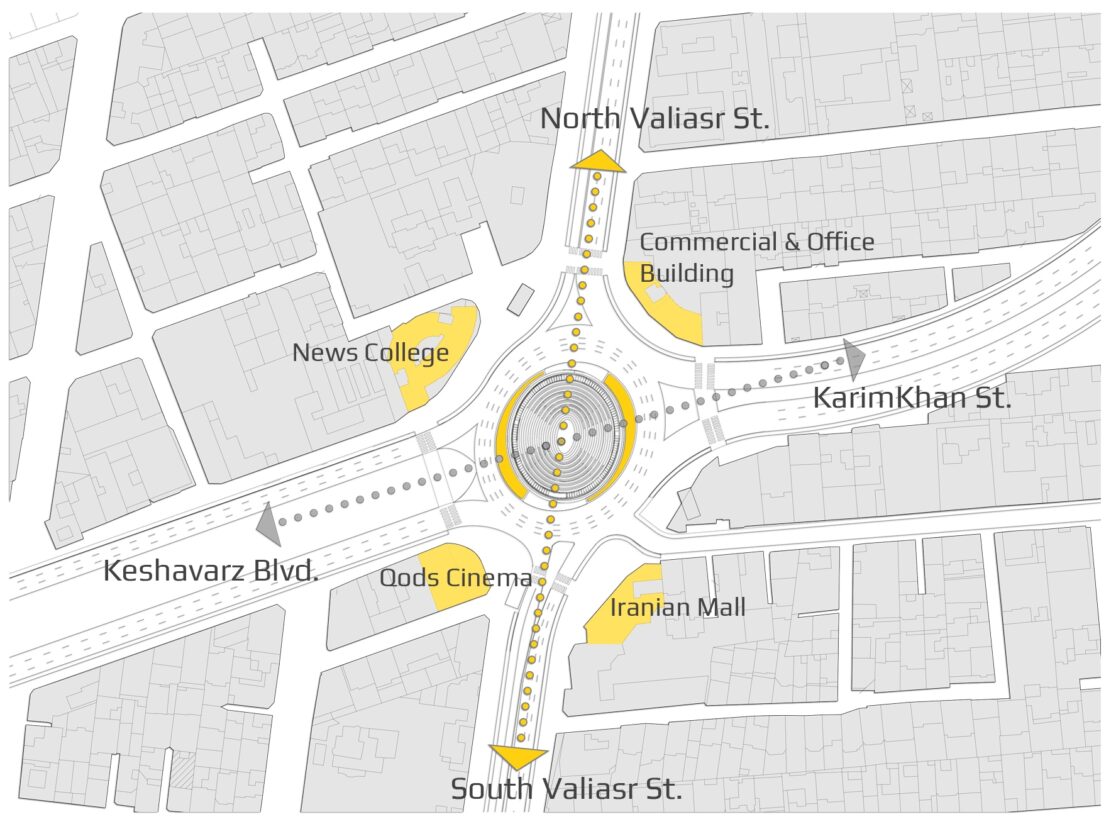

Vali-Asr square, typologically a roundabout, is the most important traffic node on the longest street in the country (17.9 km), connecting the railway station in the south to the base of the mountains to the north (1615 above sea level).

Vali-Asr square, typologically a roundabout, is the most important traffic node on the longest street in the country (17.9 km), connecting the railway station in the south to the base of the mountains to the north (1615 above sea level).

The emergence of the Vali-Asr Avenue indicates modernism’s start in Iranian urban planning and architecture. This avenue, initiated around 1925 at the old nucleus of Tehran, gradually extended as the city grew toward the mountains. During a century of development and transformation, it became the timeline of the various architectural styles in the city. With 18000 plane trees planted at equal intervals on both sides of the avenue and a series of green spaces flanking the pavements, it was supposed to refer to the ancient concept of the Persian Garden.

The emergence of the Vali-Asr Avenue indicates modernism’s start in Iranian urban planning and architecture. This avenue, initiated around 1925 at the old nucleus of Tehran, gradually extended as the city grew toward the mountains. During a century of development and transformation, it became the timeline of the various architectural styles in the city. With 18000 plane trees planted at equal intervals on both sides of the avenue and a series of green spaces flanking the pavements, it was supposed to refer to the ancient concept of the Persian Garden.

The competition, an element (landmark) for Vali-Asr Square, was stimulating and challenging at the same time. Tehran is paradoxically a megapolis with few outstanding architectural or sculptural objects. Six years ago, there was another competition with the same subject, and the jury rejected all 118 entries. The new contest was a limited competition in which 17 renowned architects and sculptors were invited to participate.

The competition, an element (landmark) for Vali-Asr Square, was stimulating and challenging at the same time. Tehran is paradoxically a megapolis with few outstanding architectural or sculptural objects. Six years ago, there was another competition with the same subject, and the jury rejected all 118 entries. The new contest was a limited competition in which 17 renowned architects and sculptors were invited to participate.

Habibeh says: “There were several sculptors among the participants, and it was clear that the client wanted a sculptural monument to locate in the center of the roundabout. In that sense, the proposal I had in mind was going to be quite provocative”.

Habibeh says: “There were several sculptors among the participants, and it was clear that the client wanted a sculptural monument to locate in the center of the roundabout. In that sense, the proposal I had in mind was going to be quite provocative”.

Iranian architecture has valued empty spaces and voids since ancient times. In Iran, “emptiness” does not mean the absence of presence but rather a spiritual presence that can be felt through geometry and symmetry. Iranian urban textures are dense and continuous. Buildings are incorporated into the urban fabric without external façades, and the building masses are organized around the voids of the courtyards.

A typical Persian square, meidan, is not just an open urban space between several independent buildings. It has a different and broader connotation. Architecturally, it should possess its own well-defined boundary and be absent of any architectural or sculptural element in the middle. From a literal point of view, the term meidan has multiple contextual meanings: circumscribed land; area of land containing; natural property; or area in which a particular force has some effect. The same term figuratively means a place where somebody appears for a critical mission and a place where a battle or sports rivalry happens.

A typical Persian square, meidan, is not just an open urban space between several independent buildings. It has a different and broader connotation. Architecturally, it should possess its own well-defined boundary and be absent of any architectural or sculptural element in the middle. From a literal point of view, the term meidan has multiple contextual meanings: circumscribed land; area of land containing; natural property; or area in which a particular force has some effect. The same term figuratively means a place where somebody appears for a critical mission and a place where a battle or sports rivalry happens.

“Paradoxically, in this case, Vali-Asr was a meidan in concept but a roundabout in shape. In such circumstances, the priority was to allow Vali-Asr square to become physically a “square par excellence“,” says the architect.

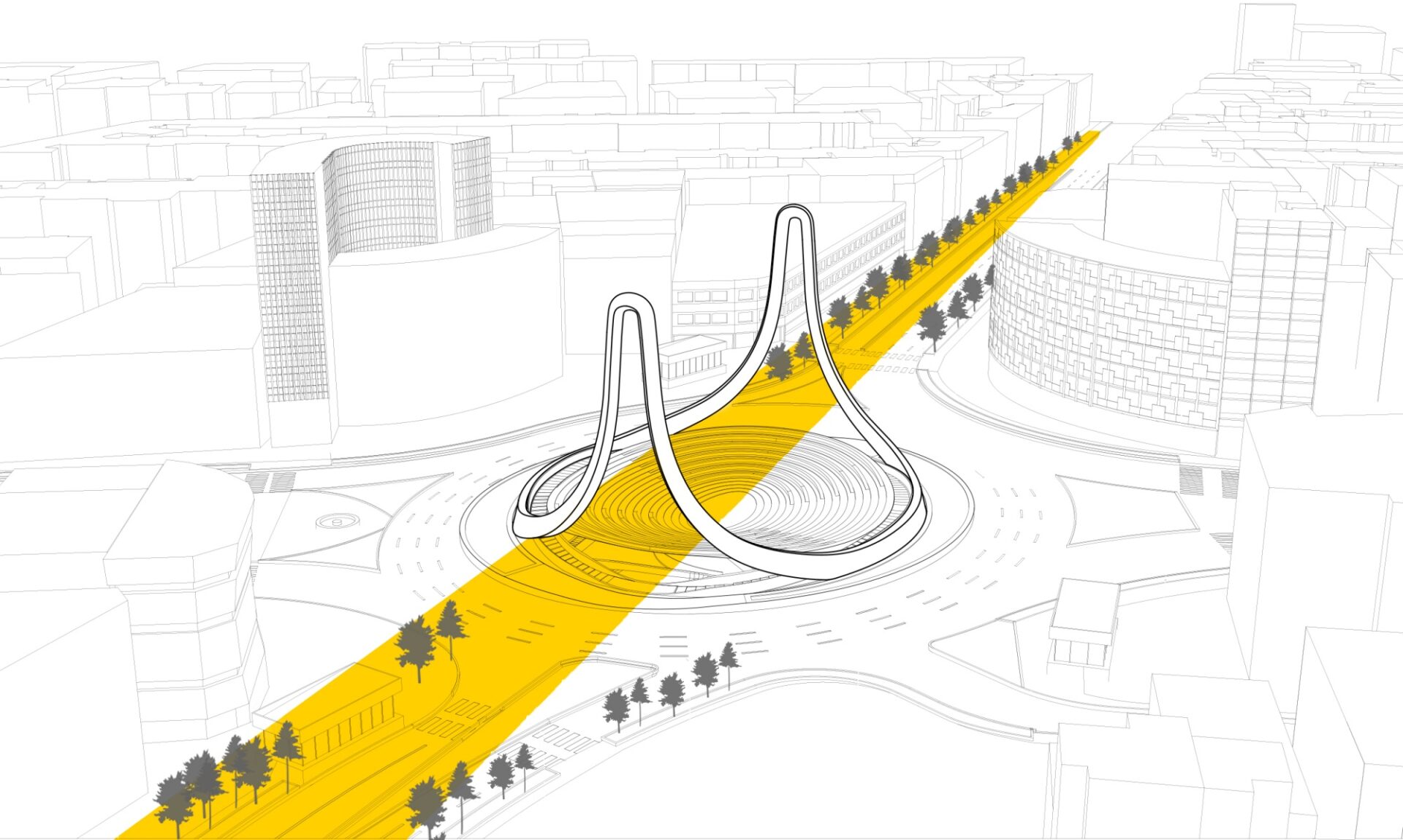

“As an architect and artist, I realised that the project has three different scales: urban design, architecture, and sculpture. So, instead of imagining an object to be put in the center of the roundabout, the project started by considering how the new square could valorise the pre-existing urban phenomena, such as the axis of Vali-Asr Avenue with its converging lined trees and the transportation infrastructures. Secondly, we focused on the organisation of the heterogenous space of the square, surrounded by different sizes and shapes of buildings, and the subway terminal in the center.

“As an architect and artist, I realised that the project has three different scales: urban design, architecture, and sculpture. So, instead of imagining an object to be put in the center of the roundabout, the project started by considering how the new square could valorise the pre-existing urban phenomena, such as the axis of Vali-Asr Avenue with its converging lined trees and the transportation infrastructures. Secondly, we focused on the organisation of the heterogenous space of the square, surrounded by different sizes and shapes of buildings, and the subway terminal in the center.

In Iranian cities, meidans have always been suitable for hosting any social and cultural events. In the proposed plan, the circular court surrounded by concentric round gradients and a well-defined boundary wall forms a suitable arena for holding all kinds of events. The arena and the ramps connecting the different levels of the square are integral parts of the emerging landmark designed when focusing on the sculptural scale of the project. The landmark does not stand in the middle; instead, with its curvy movement, it runs around the arena to valorise the central void. This sculptural form has two symmetrical peaks emphasising and framing the axis of the uphill Vali-Asr Avenue with its bending trees and pointing to the mountains in the background. The exact form descends to the ground and goes up to the opposite side, becoming horizontal in correspondence with the flat crossing street. The symmetry here was not meant to be perceived by the people moving around the roundabout. Vice versa, it was planned to allow many perspectives with the surrounding buildings in the background.

In Iranian cities, meidans have always been suitable for hosting any social and cultural events. In the proposed plan, the circular court surrounded by concentric round gradients and a well-defined boundary wall forms a suitable arena for holding all kinds of events. The arena and the ramps connecting the different levels of the square are integral parts of the emerging landmark designed when focusing on the sculptural scale of the project. The landmark does not stand in the middle; instead, with its curvy movement, it runs around the arena to valorise the central void. This sculptural form has two symmetrical peaks emphasising and framing the axis of the uphill Vali-Asr Avenue with its bending trees and pointing to the mountains in the background. The exact form descends to the ground and goes up to the opposite side, becoming horizontal in correspondence with the flat crossing street. The symmetry here was not meant to be perceived by the people moving around the roundabout. Vice versa, it was planned to allow many perspectives with the surrounding buildings in the background.

Architect/designer: Habibeh Madjdabadi

Presentation team: Hossein Bashari , Negar Asadimehr, Rashed Fatehi, Shirin Afshar, Tarranom Maveddat

Text by: Kamran Afshar Naderi