“Creating the Damascus of my Memories”

Architect Mohamed Hafez has used the art of model-making as a medium to recreate his home, his city, and his memories in miniature, touching on powerful and pertinent themes like immigration laws and anti-immigrant sentiments. By Sindhu Nair

Contained within antique mirror frames, the details of the ruins are stunningly real — electric lines hanging precariously low, towels dangling on the low-hung clothesline, TV dish antennas shining on the rooftops, chipped planters rich with green life, a dull green Merc parked outside a distinctly Islamic-looking iron door with its mesmerising geometric patterns, a bird’s nest on a pelmet and chipped and aging walls of homes well-lived.

This is the work of Syrian-American artist and architect, Mohamad Hafez. It is his world recreated, the world he had to leave behind when he came to America for his studies. It is a world that he yearns for, complete with all its sounds — of the muezzin calling for Friday prayers and the hustle and bustle of the street life in Syria — that he has reproduced for visitors at the VCUarts Qatar’s The Gallery space, inviting us into his place of comfort, of nostalgia.

“I wanted to build the Damascus of my memories,” he says.

Leveraging his background in architecture, Hafez creates photorealistic three-dimensional scenes that architecturally represent the urban fabric of the Middle East. Picture Courtesy Raviv Cohen

The memories have been so intricately recreated within mirror frames for a reason. “They look like mirror frames and people expect to see their reflection. But I see my memories and they are very nostalgic,” says Hafez.

“The nostalgic journey started way back in 2004 when I was stuck in the US for eight years without being able to go to Syria.” Thus, one day, sitting in his college studio during a holiday season when everyone was at their homes, Hafez realised that if he couldn’t go home, he could recreate it in miniature.

“I started creating these streetscapes in homesickness and the process of making and detailing these models was so very therapeutic. I kept working on it, improving it and adding to it, even as I continued with my studies and later when I went on to work as an architect in Connecticut.”

What started as a hobby kept growing, as Hafez found solace in this process of building. “There is something about this work that makes you lose track of time and encourages you to remember all the details of your home, the sounds and the memories of each window, door, or mantle. It is cathartic in its creation.”

Every detail of the post-apocalyptic city is recreated to perfection; to make the buildings, Hafez has used slabs of foam and painted them intricately to resemble concrete. He has installed small lamps in some rooms, and in one frame the lights flicker light.

Neatly catalogued and arranged on the pristine white walls of the Gallery space, the artwork that Hafez has created, along with the sounds playing subtly as a background, makes the space a Mecca of memories, a revered place that calls out to other immigrants. It attracts people and draws them into a journey seeking their place on earth, each one’s home. It means different things to different people — to a fellow Syrian, the places depicted are all too familiar; other Middle Eastern nationalities find cultural parallels in the sound of prayer, the Arabic calligraphy; while Asian immigrants feel the same pull for their hometown that Hafez distilled into his art, evoking a strong sense of nostalgia for one’s home.

Neatly catalogued and arranged on the pristine white walls of the Gallery space, the artwork that Hafez has created, along with the sounds playing subtly as a background, makes the space a Mecca of memories, a revered place that calls out to other immigrants. It attracts people and draws them into a journey seeking their place on earth, each one’s home. It means different things to different people — to a fellow Syrian, the places depicted are all too familiar; other Middle Eastern nationalities find cultural parallels in the sound of prayer, the Arabic calligraphy; while Asian immigrants feel the same pull for their hometown that Hafez distilled into his art, evoking a strong sense of nostalgia for one’s home.

Before the war ransacked Syria, Hafez managed to go to his hometown in 2011, a stay that got prolonged due to visa formalities. During this homecoming trip, Hafez absorbed the Syrian culture with newfound fascination, as if saving up all that he loved for the days when he would be away. He had recorded the street sounds and prayer calls that embellish the atmosphere at the VCUarts The Gallery space.

Before the war ransacked Syria, Hafez managed to go to his hometown in 2011, a stay that got prolonged due to visa formalities. During this homecoming trip, Hafez absorbed the Syrian culture with newfound fascination, as if saving up all that he loved for the days when he would be away. He had recorded the street sounds and prayer calls that embellish the atmosphere at the VCUarts The Gallery space.

“All I did every day was walk around old Damascus, recording everyday life with my phone.”

Each part of the frame is created from baubles collected by Hafez on his journey of assemblage. “In Syria, we have many old Soviet cars. Peugeots, Renos, Mercedes, and BMWs are a very big part of the Syrian social fabric. Generations have grown up around these cars,” he says.

“The fabric used on the laundry lines, called aghabanni, is from Syria. During my last trip before the war, I asked a textile merchant to give me some of his fabric scraps. Each little piece is attached to some nostalgic memory,” he remembers.

“The fabric used on the laundry lines, called aghabanni, is from Syria. During my last trip before the war, I asked a textile merchant to give me some of his fabric scraps. Each little piece is attached to some nostalgic memory,” he remembers.

Hafez has also created other art forms, each a reflection of his state of mind. When the horrors of the Syrian war playing out on the news channels started affecting the architect, especially stories of refugees seeking asylum, he embarked on ‘UNPACKED: Refugee Baggage’, seeking to humanise the word ‘refugee’. Created during the summer of 2017, in this multi-media installation, Hafez sculpturally re-creates rooms, homes, buildings, and landscapes that have suffered the ravages of war.

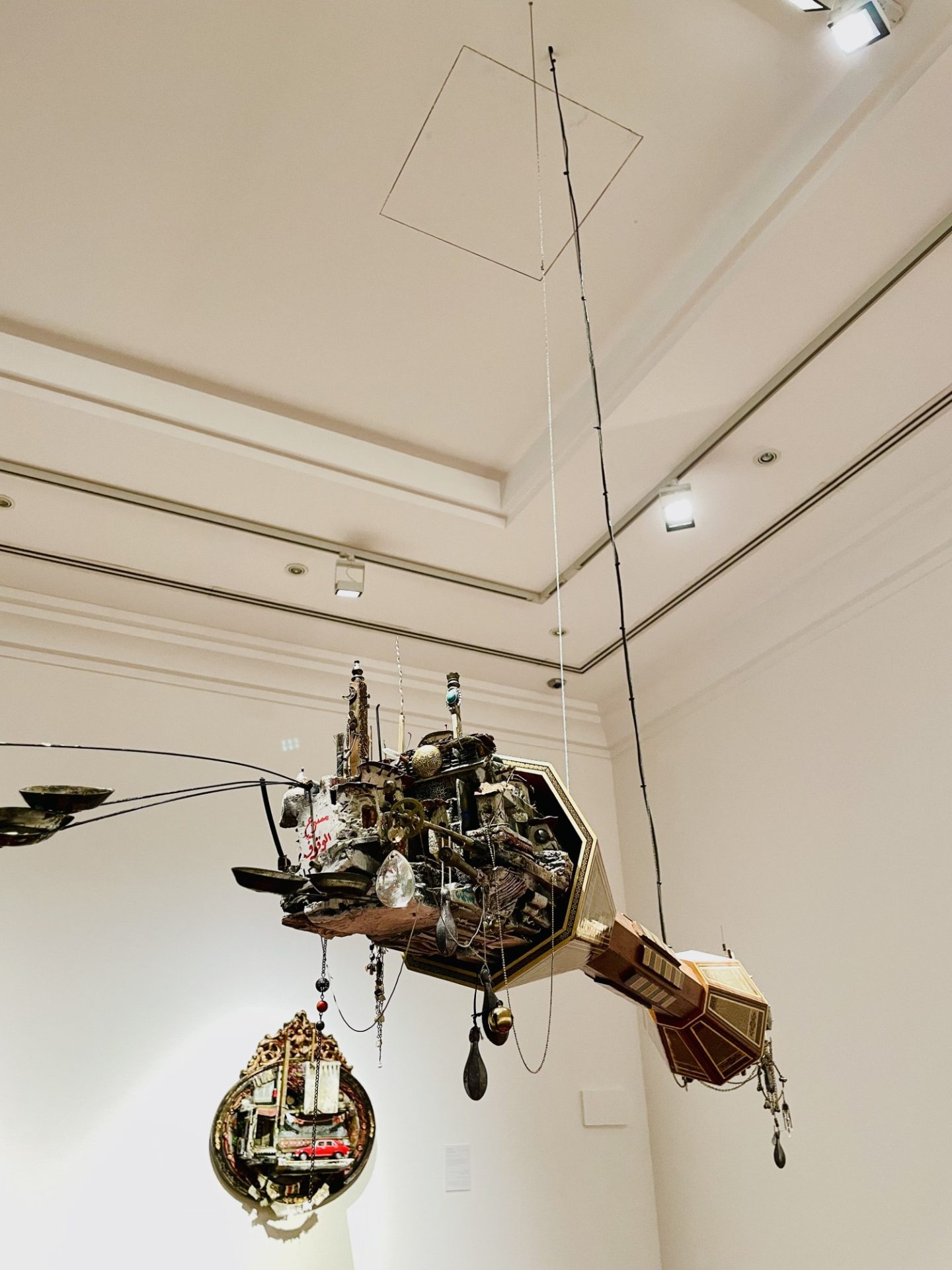

Tower of Dreams takes centre stage within the VCUarts The Gallery space and is meant to resemble a rocket propeller or a bazooka. “But instead of shooting a missile, it shoots out the misery, the devastated lives of the people, the rubble and the destruction that follows in the missile’s aftermath,” he says.

Tower of Dreams takes centre stage within the VCUarts The Gallery space and is meant to resemble a rocket propeller or a bazooka. “But instead of shooting a missile, it shoots out the misery, the devastated lives of the people, the rubble and the destruction that follows in the missile’s aftermath,” he says.

The Tower of Dreams conveys a sense of statelessness says Mohamed Hafez. Picture Courtesy: Aadhil Naleer

Hanging from the ceiling, the Tower of Dreams sways gently, “meant to resonate the stateless feeling, of not belonging anywhere, of being rootless in the country you have immigrated to,” says Hafez, whose work has taken on new resonance as a vehicle for dialogue about immigration and about the then rising anti-Islam sentiments in the US.

Hanging from the ceiling, the Tower of Dreams sways gently, “meant to resonate the stateless feeling, of not belonging anywhere, of being rootless in the country you have immigrated to,” says Hafez, whose work has taken on new resonance as a vehicle for dialogue about immigration and about the then rising anti-Islam sentiments in the US.

“A Broken House”, a documentary directed by Jimmy Goldblum, follows Hafez’s story of memory-building and has qualified as one of the 15 shorts to make the coveted Oscar shortlist this year. It had earlier won two awards at the Palm Springs International Shortfest in 2021.

“I had the pleasure of working with Jimmy. We filmed day and night in my studio in New Haven and also in Beirut. I was in a special mood at that time — homesick and not paying too much attention to what was happening — which worked very well in the movie because it became an honest portrayal and a realistic story,” he says.

While the entire process of creating models and making the movie has been therapeutic for Hafez, one can sense his deep sorrow, of not meeting his mother in familiar surroundings, of meeting her in a third country, in Beirut or Dubai, of his family scattered in different parts of the world. Yet, he focusses on hope as the message that he wishes to convey.

“We are not people of despair. We harbour peace. There is a verse from Surah al-Inshirah, one of the most beautiful verses in the Quran that translates as “Indeed, with hardship, [will be] ease.”

All Images Courtesy VCUarts Qatar

Photography by Raviv Cohen and Aadhil Naleer

.