Shirley Surya on Curating Life in Architecture: I. M. Pei

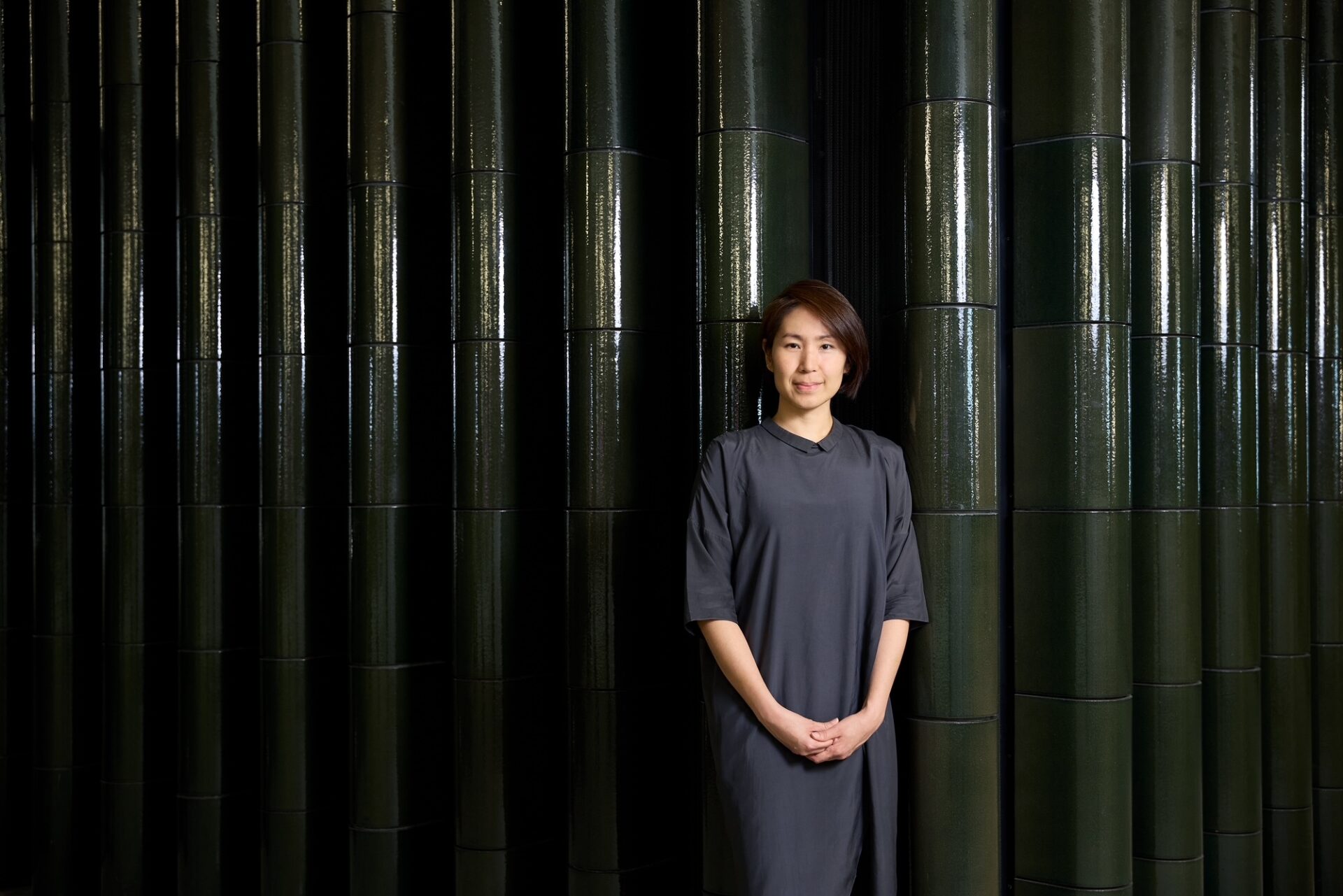

Shirley Surya, Curator of Design and Architecture at M+, Hong Kong, has devoted seven years to developing the first full-scale retrospective of architect I. M. Pei. Organised by M+ and curated by Shirley and Aric Chen, currently the Director of the Zaha Hadid Foundation, London, the exhibition builds upon years of research by M+, and arrives in Doha following acclaimed presentations in Hong Kong in June 2024 and Shanghai in April 2025. The exhibition is now in Doha, a city Pei helped define through the Museum of Islamic Art. Shirley Surya speaks with SCALE about the intellectual labour behind the exhibition, the discoveries made in archives across continents, and why Pei’s legacy matters today, especially here in Doha. By Sindhu Nair

The exhibition was officially unveiled by Her Excellency Sheikha Al Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, Chairperson of Qatar Museums, seen here in the presence of Sheikha Reem Al Thani, Acting Deputy CEO of Exhibitions, Public Art, and Rubayia Qatar at Qatar Museums; Shaika Nasser Al Nassr, Director of MIA with Shirley Surya, Curator, Design and Architecture, M+ as well as other prominent dignitaries, architects, artists, and cultural leaders from Qatar and around the world.

Shirley Surya’s dedication to the exhibition is unmistakable, you sense it in the way she speaks, in her immersion in the archives, and in her complete commitment to understanding I. M. Pei’s world. Yet, as a curator, Shirley remains deliberately at a distance from her subject. She resists the temptation to glorify the architect’s genius alone. Instead, she aims to reveal through the work of Pei that architecture is fundamentally collaborative, negotiated, and a deeply contextual practice, one shaped by place, politics, public perception, and even commerce.

Her Excellency Sheikha Al Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, Chairperson of Qatar Museums, viewing the exhibition.

For her, these forces are not peripheral; they are vital to understanding how architecture truly operates.

“Architecture is shaped by commerce, and commerce is “not a dirty word,” but a force that can be harnessed for good, especially in architecture, where revenue, movement, and public space are intertwined,” says Shirley.

She hopes the exhibition helps the public understand that they, too, are clients: their perception, behaviour, and aspirations shape what architecture becomes.

Pic Courtesy @Qatar Museums

SCALE: This exhibition is described as the first full-scale retrospective of I. M. Pei’s seven-decade career. What was the starting point for you and your team?

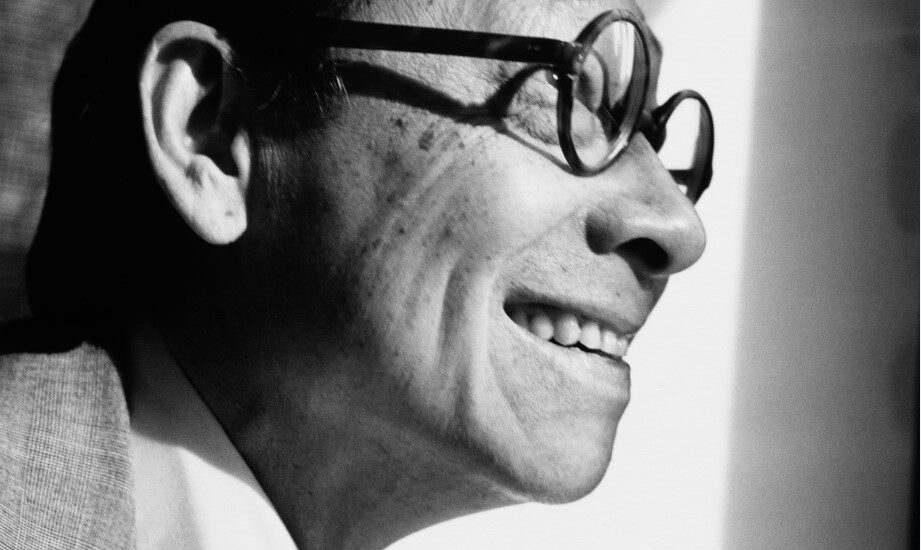

Shirley: It began with M+ itself, before we had a building, we had a mission as an institution to build a collection, a collection that is meant to be informed by where we are. So, our intention has always been to build a collection shaped by Hong Kong’s position in Asia, but our frame work is utterly transnational because Hong Kong is undeniably transnational. Our aim has been to create a collection that speaks to the region and yet is also international. At that time in 2012, our Design and Architecture team was only two people and very early on, Aric Chen made the case that if we were serious about collecting architecture, Pei had to be central.

We approached his son, Sandi Pei, in 2013 with the intention to collect and eventually exhibit his work, even though most of his archive was believed to be unavailable, stored at the Library of Congress. Still, we persisted.

It took Pei three years to say yes, in 2016. He wasn’t someone who promoted himself. He felt the books on his work were enough; no one had ever done a full exhibition. And after Pei said “yes”, the first thing we did was to organise a symposium, Rethinking Pei: A Centenary Symposium, with Harvard GSD and HKU, because we insisted Pei was famous but understudied, especially outside Euro-American spheres.

SCALE: Pei’s career spanned continents. How did you decide which projects to highlight, and how did you balance global modernism with sensitivity to local contexts?

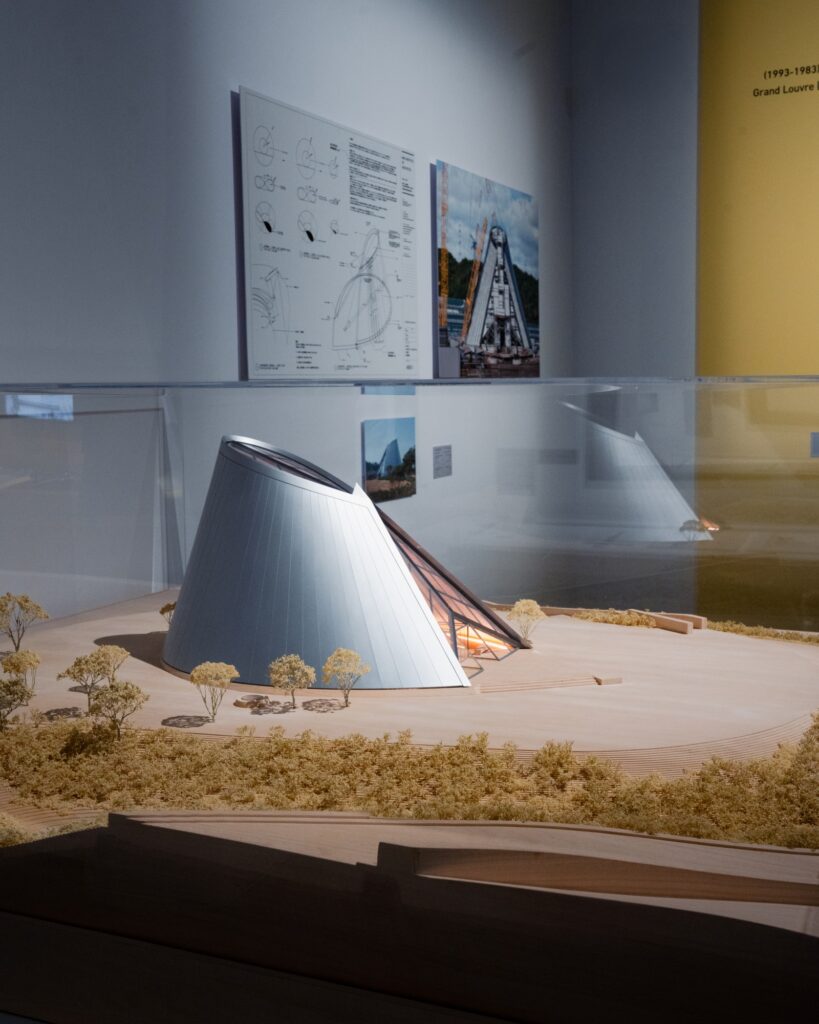

The models within the exhibition from the Real Estate and Urban Redevelopment section.

Shirley: We allowed six themes to shape the selection. Projects weren’t chosen for star value; they were chosen because they illuminated an idea, about urbanism, art, materiality, identity, or transnational histories.

Pei’s early involvement in real estate and urban redevelopment at Webb & Knapp was critical. It taught him to see buildings as operating within urban, economic and political forces, not in isolation. That informed even his later towers, like the Bank of China, which were not single objects but part of negotiated urban terrains.

And we needed to restore his impact across a wider geographical breadth, especially in Asia, Singapore, Taiwan, mainland China, because Western narratives often overlook these. Many of these projects only came to light when we accessed newly discovered materials in the Pei Cobb Freed Architects warehouse in 2018.

SCALE: The exhibition is organised into six themes. How did these emerge?

Pei’s undergraduate thesis ‘Standardized Propaganda Units for War Time and Peace Time China’

Shirley: The themes draw from the symposium and years of research. Some themes were expected, like material and structural innovation, but others came from rethinking Pei’s identity:

Pei’s Cross-cultural Foundations: We avoided framing him as simply “East meets West.” His upbringing in Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Suzhou created a layered, sometimes conflicting sense of identity that shaped his cultural and spatial sensibilities.

Real Estate & Urban Redevelopment: The least understood part of his career, yet foundational to his thinking and one that we thought was vital to his overall practise.

Art & Civic Form: His museum architecture cannot be separated from his understanding of art, relationships with artists and art institutions; as well as the belief in museums as a form of civic space.

Material and Structural Innovation: While this topic is typically addressed in architecture exhibition, we divided this section to “Concrete Visions” and “Glass and Steel” to reveal the breakthroughs Pei’s team made in building with concrete which was underrepresented and the reason behind his transition to utilising glass and steel.

Power, Politics and Patronage: reveals how Pei, with his technical mastery, ingenious problem-solving, and sensitivity to client needs, became a trusted collaborator in high-profile commissions that drew both immense support and public controversy throughout his career.

Reinterpreting History through Design: Pei’s reference to tradition is often misread through a postmodern lens; we returned to Pei’s own early writings and unrealised proposals, as early as his graduate school thesis at Harvard, and projects situated in China-related geographies and beyond to understand his deeper motivations and how he derived a spatial and formal logic from architectural precedents to address contemporary needs of his projects.

These themes allowed us to cut across geographies and decades, revealing connections between projects that are rarely discussed together.

SCALE: With more than 400 objects on display, were there particular discoveries that changed your view of Pei’s process?

Pic Courtesy @Qatar Museums

Shirley: Several were revelatory.

The interview transcript of the process of Pei’s design for the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) was extraordinary. Pei described being intimidated by the Flatirons rocky mountains and spent long periods simply picnicking over wine at the wide open landscape observing light and reflecting on scale before drawing anything. Seeking that sense of intimacy and humility toward the land is rare today.

Another discovery was Pei’s involvement with the design of Tunghai University campus in Taiwan, which included the Luce Memorial Chapel. It was a “moonlighting” project done while Pei was still heading the design firm as part of the real estate developmer Webb & Knapp. Taiwanese architects long assumed Pei played a minimal role, but we found letters and drawings, extremely detailed correspondence conducted without fax or email, proving his deep involvement in the design process. These were culturally meaningful discoveries, revealing his enduring ties to China and the region.

We also traced his firm’s pioneering role in concrete technology since the 1950s in the design of low-income housing like Kips Bay in NYC and earlier museums like Everson Museum in Syracuse. But his use of concrete was much more sculpted and toned down, especially in the case of NCAR when concrete was transformed into one with the texture and colour of surrounding rock formations by adding a reddish-brown stone aggregate extracted from a nearby quarry.

We also uncovered lesser-known projects like Pei’s involvement in the design of the Taiwan Pavilion at the Expo ’70 in Osaka as well as other student and unbuilt projects that illuminate Pei’s intellectual evolution in ways no monograph had captured.

Pic Courtesy @Qatar Museums

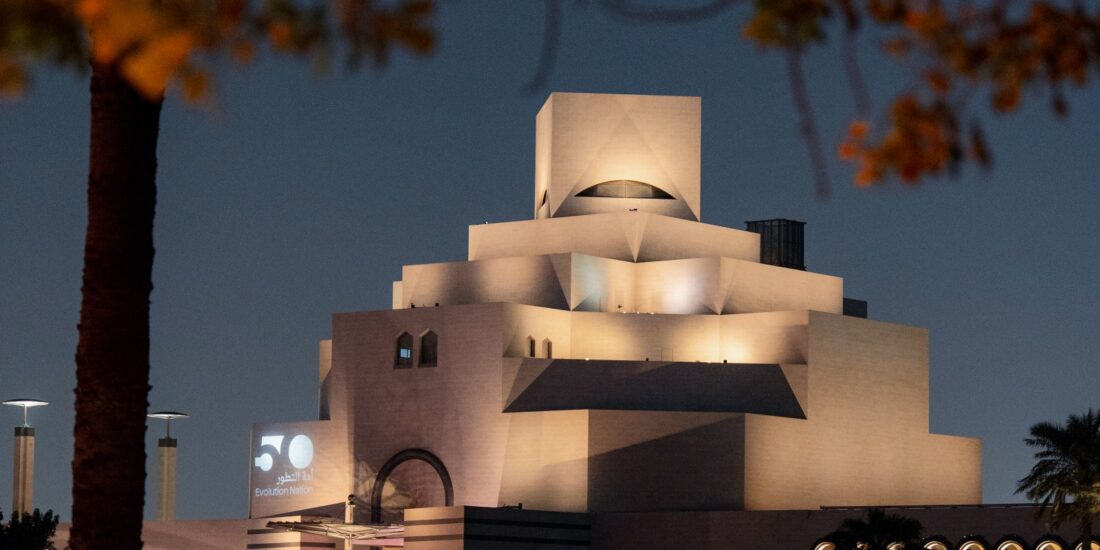

SCALE: Doha holds a special place in Pei’s story. Did curating this in Doha change its resonance?

Pic Courtesy @Qatar Museums

Shirley: The exhibition is presented in Doha exactly as it appeared at M+, Qatar Museums did not request content changes, and only two objects were omitted due to loan logistics. But the context in which this exhibition is presented changes everything.

Seeing the Museum of Islamic Art (MIA) for the first time was deeply moving for me. I had only seen images. In person, its siting reveals so much about Pei’s genius: its placement away from the crowded skyline, being set apart on reclaimed land, views of the city from within, its quiet monumentality. Pei negotiated for the right siting, as he would for many other projects, because he believed the building’s siting was inseparable from how the building would be used, perceived and constructed.

Pei possessed a rare authority in architecture, the ability not just to design a building, but to shape the conditions under which it could exist. Most architects inherit sites as fixed constraints. Pei, however, negotiated them, something which architects rarely could, or would, do.

For MIA, he pushed for reclaimed land, distancing the museum from Doha’s growing skyline. He understood the city’s ambitions, anticipated future expansion, and positioned the building where it could retain its dignity and visibility.

He understood Doha’s ambitions as a growing city and insisted the museum should not be buried among towers. His decision to push the building to the edge of its reclaimed peninsula echoes his fascination with the Ibn Tulun mosque’s eccentric siting, slightly off-centre, yet commanding.

In Doha, Pei’s architectural philosophy becomes palpable. It also touches on his negotiation skills and far-sighted reading on the ambitions of the city he was building for.

SCALE: The exhibition highlights Pei’s collaborations with artists. What can architects learn from this?

Work of Cai Guo-Qiang, one of the artists with whom Pei worked and had a strong bond of friendship.

Shirley: Pei viewed art as a conceptual partner, not an accessory.

He once commissioned a figurative sculpture and considered it a failure because it couldn’t be scaled up to be in dialogue with the building he designed. After that, he turned to abstraction. Henry Moore, Picasso, and Alexander Calder were some of the artists he chose to work with to created sculptural works that could form productive tension with the texture and geometry of his built work. As large-scale sculptures they also mark public space and engage people in ways that his building couldn’t.

His collaborations also reveal his sensitivity to material counterpoints, bronze against concrete, stone against glass, and his understanding of museums as ecosystems where art, architecture, and movement shape one another.

SCALE: How does the exhibition address moments of public tension, such as the Louvre Pyramid?

Pic Courtesy @Qatar Museums

Shirley: We situate the Louvre within the theme of ‘Art and Civic Form’ and ‘Power, Politics and Patronage’. The pyramid alone cannot explain the project’s ambition. Pei reimagined the Louvre as an interconnected, subterranean civic network, linking galleries, transit, retail, circulation, even the urban infrastructure of Paris.

We show press criticism, political debates, and documentary footage. Some accused him of creating a “Disneyland.” Yet his approach, combining public circulation, revenue models, and visitor experience, is now the global norm.

Importantly, the project only happened because President Mitterrand and the museum’s curators were aligned with Pei’s vision. Architecture cannot be separated from statecraft and public perception. The exhibition captures that political choreography.

Pic Courtesy @Qatar Museums

SCALE: Why is revisiting Pei important now?

Shirley: Two urgent reasons:

Shirley: Two urgent reasons:

Firstly, how Pei’s projects demonstrate the importance of siting and neighbourliness. Contemporary architecture often prioritises isolated objects. Pei thought 5–10 times beyond the site’s boundary. He negotiated setbacks for the building he designed in Hong Kong, introduced greenery where none existed, planned for future urban growth, and designed so his buildings could coexist, not dominate.

Second, identity with depth. Pei rejected superficial cultural-historical symbolism, like the cliché that Chinese architecture equals upturned roofs. For him, identity was spatial, experiential, atmospheric. The Expo ‘70 Taiwan Pavilion in Osaka, for instance, was pure geometry, yet the Taiwanese government accepted it as undeniably “Chinese” because of the way the path and spatial sequence evoked the Chinese garden and courtyard, but in a vertical way, without literal motifs.

In a time preoccupied with instant iconography, his rigour offers a necessary corrective.

SCALE: How has your curatorial practice shaped your approach, and what personal insights have emerged?

Miho Institute of Aesthetics Chapel (2008–2012), Shigaraki, Shiga Pic Courtesy @Qatar Museums

Shirley: When I was first asked to co-curate this show, I resisted. Pei was “too famous,” and as a historian I was more drawn to unknown architects. But the project humbled me. I understood that even the most well-documented architects contain layers waiting to be uncovered, if you ask new questions.

The process taught me to appreciate the public’s emotional connection to Pei, and how exhibitions can honour that while still offering new knowledge.

Another major insight came from model-making. We built six new architectural models, some of unbuilt or vanished projects, and chose to produce them in a way that became a learning process for students, fabricators, and the curatorial team. For me, this reinforced that architecture exhibitions thrive on collaboration. Displaying architecture is complex: it requires drawings, films, models, archives, and multiple ways of seeing.

Ultimately, the work deepened my understanding of how architecture sits within economy, politics, culture, and public agency.

Architecture isn’t just designed, it is negotiated, debated, funded, resisted, and then loved.

SCALE: Can you speak about the importance of Pei’s childhood and how it shaped his architecture?

Pic Courtesy @Qatar Museums

Shirley: Pei’s childhood is absolutely fundamental to understanding his architecture. One could argue that everything he designed later in life, from the serenity of the Museum of Islamic Art to the spatial cadence of the Louvre, can be traced back to the three cities that shaped him early on: colonial Hong Kong, semi-colonial Shanghai, and classical Suzhou.

In Hong Kong, Pei witnessed a colonial modernity, dense urban fabric, and the orderliness of British civic structures. In Shanghai, he saw a cosmopolitan city layered with competing influences: Chinese, European, missionary, mercantile. And in Suzhou, where his grandparents lived, he encountered the intimate, slow, choreographed spatial sequences of Chinese gardens, which profoundly shaped his understanding of movement, courtyards, thresholds, framed views and cultural specificity.

This mix of environments created transcultural foundations. It wasn’t East versus West — it was East and West, and everything in between. He grew up negotiating contradictions, and that negotiation later became his design language.

Pei himself insisted that “Chineseness” in architecture was not about symbols or surface motifs, not about upturned roofs or ornament, but about how space is experienced. That insight comes directly from his childhood memories of the Suzhou gardens, where paths bend, light shifts, and rooms unfold slowly.

At the same time, Hong Kong and Shanghai taught him to think about the modern city, the realities of politics, density, and urban life, all of which surface in his later urban work, from his redevelopment studies in American cities to the design of Bank of China Tower on a challenging site in Hong Kong.

Even his student projects at MIT and Harvard were sited in China, revealing how deeply he felt for the national and cultural conditions of the country. The emotional and cultural threads of his childhood contributed much to the intellectual framework of his entire practice.

So, the importance of his childhood isn’t incidental, it is the lens through which his entire body of work becomes legible.

SCALE: Do you have favourites among Pei’s works?

Hyperboloid (1954–1956; unbuilt), New York; Pic Courtesy @Qatar Museums

Shirley: NCAR (National Center for Atmospheric Center) remains a favourite, even though I never visited it. The way it both melds into the landscape while asserting its presence strikes a perfect balance between modesty and confidence.

The Expo ‘70 Taiwan Pavilion is another: an abstraction of the Chinese garden without a single recognisable symbol or overt gesture. Pure geometry, pure space — yet culturally resonant. It captures Pei’s belief that identity can be felt rather than illustrated.

SCALE: One word to describe your experience curating this retrospective?

Shirley: A single word is difficult. But if I must choose: a privilege, one that has been both humbling and transformative.

Main Portrait of Shirley Surya, Curator, Design & Architecture, M+ and Co-curator of I.M. Pei: Life is Architecture, Photo: Winnie Yeung @Visual Voices, Image Courtesy of M+, Hong Kong