Art That Unites the Indian Ocean Basin

A project that finds artistic connections around the Indian Ocean basin to study the visual, material, and built cultures that have emerged from early maritime encounters was born in Doha and is under progress. We talk to Nancy Um who heads the Indian Ocean Exchanges programme funded by the Getty Foundation, through its Connecting Art Histories initiative, that lays the groundwork for a durable and tight-knit international research community that is equipped to study, connect and articulate the complex interactions that have shaped – and continue to shape – art across the Indian Ocean. By Sindhu Nair

Long before the first European ship entered this seascape in the late 15th century, the Indian Ocean connected the artistic traditions of the Asian, Middle Eastern, and African worlds. Covering more than 27 million square miles, the Indian Ocean is a vast expanse of water. It extends from the eastern coast of Africa into the Red Sea and around the Arabian Peninsula, where it bridges the Gulf, the coast of Iran, and the Arabian Sea, and joins South Asia, which constitutes its geographic centre. Southeast Asia forms its eastern edge, as a band that is anchored in the landed north and extends to the south through its peninsula and islands. Rather than a barrier between these locales, the Indian Ocean has served to connect them. For centuries, both near and distant neighbours have shared and exchanged, but also imposed, their cultures on one another, creating densely imbricated coastal sites and material environments that bring together multiple aesthetic, commercial, religious, intellectual, and linguistic traditions. These circumstances became the backdrop for Nancy Um’s early interest in art that connected the countries around the Indian Ocean.

But why is Qatar important in these connections?

“Qatar possesses several important port cities and has a long history as a place of exchange. We visited two sites; Mirwab and Zubarah along with our colleagues, archaeologists in Doha. Qatar has really distinguished itself as a crossroads of Indian Ocean heritage in many ways. MIA will be opening its reinstalled display that will reassert the importance of the Indian Ocean as a connector of art and artefacts around the region. Meanwhile the QNL has facilitated global access to information on maritime heritage in Qatar, the Gulf, and the Indian Ocean through its Digital Library,” she says.

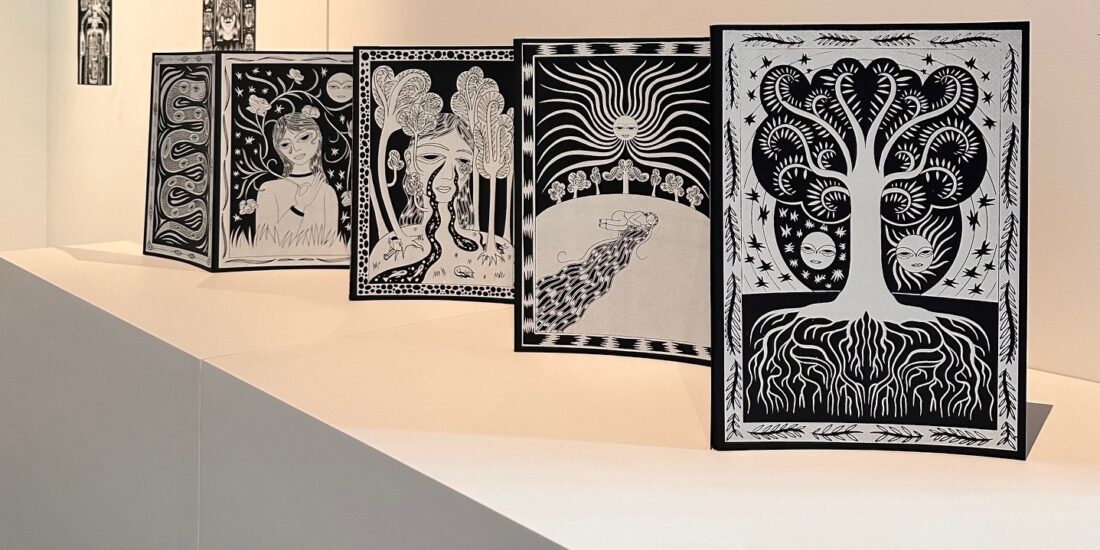

Images from VCUArts Qatar Doha ; first stage of peer review of their research projects and begin the work of compiling an extensive online bibliography on Indian Ocean art history.

It is more than a coincidence, says Nancy Um, Programme director of Indian Ocean Exchanges that this project took off in Doha in 2019 when she was here for the Hamad Bin Khalifa Symposium organised by Virginia Commonwealth University of Arts Qatar, where she organized a panel on the topic of Indian Ocean port cities. Soon afterwards, someone from the Getty Foundation who was also attending, approached her, indicating the potential for funding such a programme.

In a sense, Qatar will help shape the future direction of the Indian Ocean Exchanges programme as it ignited important discussions and findings that will be continued in the next two study trips that will take place in 2022 and 2023.

And that is how Um is here now, three years lost to the pandemic but finally having interactive, real-time conversations to discuss the progress made. But it is no coincidence that Nancy Um has spearheaded this programme and that Getty found it important to help fund this programme as Um is an art historian with over 20 years of experience researching on countries around the Indian Ocean.

She began a long time back in the 1990s, when she was a doctoral student in the University of California. She had a particular interest in the coffee trade in Yemen and she began to look at the ways in which the port cities specially those in the Red Sea, the Port of Mocha in Yemen, brought together the cultures of areas around it.

Square-based, mold-blown, and gilded glass vessels that were made in India in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and have been cast under the wider rubric of “Mughal glass.”

”By connecting these decorated flasks to similar containers made of porcelain in Japan, we may understand the key role that they played as gifts, filled with aromatic oils, packaged in custom-made boxes, and delivered to high-profile recipients around the Indian Ocean. Rather than isolated items of decorative interest,” says Nancy Um.

“I realised that we have to look at the Indian Ocean as a connector not as a divider. I was particularly interested in understanding the maritime cultures that connected regions across religion, language, cultural diversities, and national boundaries. I was one of the only ones in the beginning, kind of pioneering this interest but soon, a significant a group of like-minded people who were actively exploring this thread and trying to connect dots emerged,” says Um, quite modestly, though she stresses that while there were many historians who were interested in the trails of the Indian Ocean, in the 1990s there were very few who were interested in the art history, “There were many historians who were interested in the legacy of the European companies, they were studying the documents of the English and Dutch East India Companies but there were not many who were interested in the art or the architecture or the material history. We realised that this material is vast and it tells a very different story from those found in documents, trade records. Heritage and cultural production is a huge part of the story.”

Case with nine bottles, ca. 1680–1700. Batavia (box) and Japan (bottles). Calamander wood, underglaze painted porcelain, silver, velvet; box: 10⅝ × 10⅛ × 6½ in. (27 × 25.5 × 16.5 cm); bottle height, with cap: 6 in. (15 cm). Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, NG-444. Image in the public domain..

The Indian Ocean basin is an exciting laboratory for the art historian, yet the field has been slow to develop the trans-oceanic approaches needed to study the visual, material, and built cultures that have emerged from these maritime encounters. In recent years, however, a new generation of scholars has begun to work seriously on the Swahili coast of East Africa, the edges of the Arabian Peninsula and the coastlines that face it, and the shores of South and Southeast Asia, producing fruitful research in the emerging domain of Indian Ocean art history, shares Um.

The 15 participants of the programme hail from many different countries including India, Pakistan, Kenya, Mozambique, Indonesia, Singapore, South Africa, the UK, Canada, and the US. “These emerging scholars represent the future of Indian Ocean art history,” says Um.

Stories of merchants who were either based in India or in the Arabian Peninsula, were the most interesting to Um, she says as she recounts a poignant story. “One of my favourite merchants was called Mullah Mohammed Ali based in Surat, in Gujarat. He was the adopted grandchild of the famous merchant Abdul Ghafoor who was a major shipping magnate. In the early 18th century, Mohammed Ali used to send boats every year to the port city of Mocha in Yemen. His boats were received with much fanfare and even though he rarely made it to the city, his name was well-known there. He was a great patron of architecture and he had even refurbished a minaret in the most famous mosque in Mocha and the minaret was used by the ships to navigate their boats safely through the harbor. He even had a house that was known by his name and though he rarely visited, he was a well-known merchant who had a reputation that was transnational. Even if he rarely made the journey these networks were so closely maintained long before the technology of the internet, for instance, made it easy for communication.”

While in Qatar, the closed-door research seminars provided the opportunity for the participants to delve into local sites and collections. They engaged in the first stage of peer review of their research projects and begin the work of compiling an extensive online bibliography on Indian Ocean art history. The week will close with a public scholarly event, hosted at VCUarts Qatar, entailing a series of lightning talks delivered by the participants and framed by project team members.

“The tangible outcome of this programme will not be published but will be in the formation of communities who will support the cause for a longer duration, which is why this meeting in Qatar is so important as it will set the ball rolling and will continue in future transnational connections,” says Um.