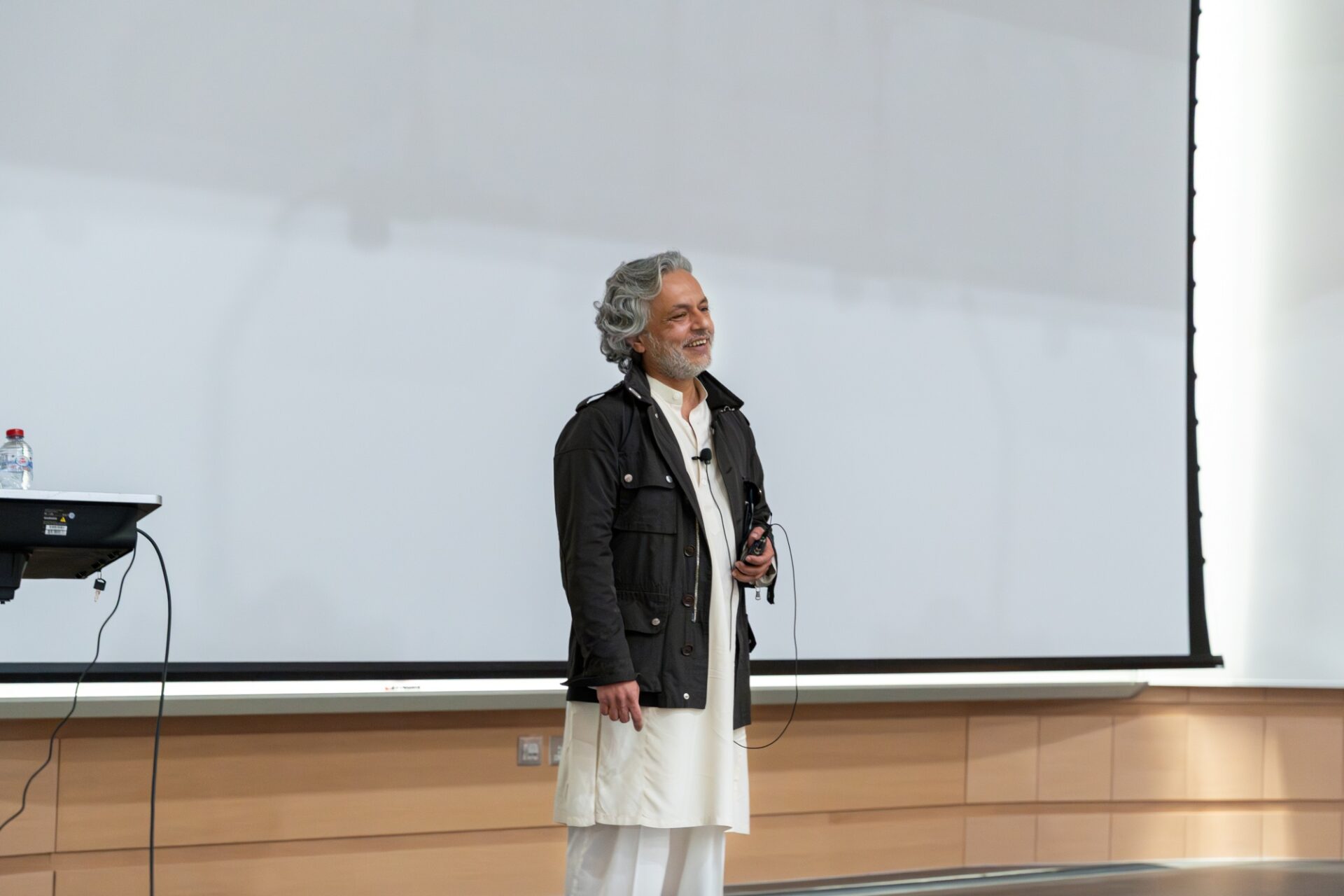

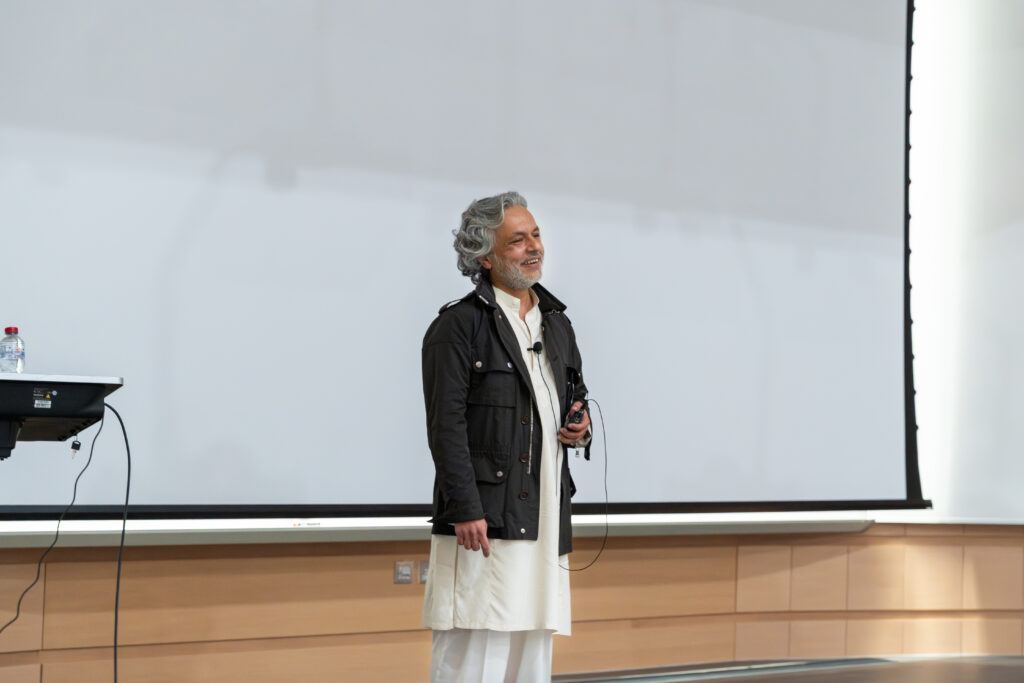

Attiq Ahmed on Rethinking Architecture and the City

Architecture, for Attiq Ahmed, is inseparable from climate, culture, and civic life. Participating in Qatar Museums’ Architectural Programme, Architecture and Design: Turning Vision Into a Universal Dialogue, the Lahore-based architect reflects on Pakistan’s evolving architectural identity, the power of adaptive reuse, and why reducing energy use and automobile dependence is no longer optional. Drawing from vernacular knowledge and contemporary practice, he argues for cities shaped by intention rather than predictability.

Focusing on Lahore, Pakistan, the session by Atiqq highlighted how traditional approaches to climate, spatial planning, and urban form can be reinterpreted to address the challenges of the twenty-first century

“Climate impacts are not immutable. With intentional shifts in how we build and live, it is still possible to change the trajectory,” says Attiq Ahmed. Pakistani architect, urban designer, and academic based in Lahore, Attiq Ahmed is known his work in contemporary design, urbanism, and furniture design, often blending modern approaches with vernacular lessons.

Attiq’s words arrive without embellishment, but with clarity. They frame architecture not as an aesthetic pursuit, nor even as a technical discipline, but as a set of choices, spatial, material, and cultural, that carry long-term consequences. Speaking as part of Qatar Museums’ Architecture and Design Program led by Al Riwaq, Attiq situates his practice within a broader regional and global conversation about climate vulnerability, urban density, and the urgent need to rethink how cities function.

Based in Lahore, Attiq’s work operates at the intersection of historical memory and contemporary need. His architectural thinking is deeply shaped by the material intelligence of South Asian cities, where buildings have long negotiated heat, density, and social life through spatial ingenuity. For him, architecture today must return to these lessons, not by replicating the past, but by critically reinterpreting it.

An Architectural Identity Shaped By Memory

Pakistan cityscape.

Asked how he defines Pakistan’s architectural character today, Attiq resists singular narratives. He describes a condition shaped by tension and overlap. Pakistan’s architecture, he explains, exists at the crossroads of deep historical memory and rapidly evolving contemporary expression.

“In cities like Lahore, the enduring legacy of red brick continues to operate as both material and metaphor, informing a design language that interrogates tradition while critically engaging with modernity,” he says.

This persistence of brick is not nostalgic. Rather, it offers architects a means to interrogate tradition while engaging modernity critically, instead of adopting imported aesthetics detached from context. Looking forward, Attiq sees Pakistan’s architectural trajectory moving toward practices that draw more intelligently from historic materials and spatial traditions, reframing them through contemporary lenses rather than abandoning them altogether.

Adaptive Reuse As a Civic Act

Muhatta Palace in Karachi

In dense cities like Karachi and Lahore, adaptive reuse remains limited, often overshadowed by demolition-driven development. For Attiq, this is a missed opportunity. Meaningful adaptive reuse, he argues, must go beyond preservation as an end in itself. It must actively reframe a city’s cultural and social narratives, allowing architecture to re-enter public life in transformative ways.

He points to the Muhatta Palace in Karachi as the most compelling example of reuse done right.

“Once a deteriorating private residence facing the threat of demolition, the building was reclaimed through collective civic effort and transformed into a public museum. Today, it functions not merely as an exhibition space but as an active urban forum, hosting book launches, lectures, exhibitions, and public gatherings. In doing so, it reconfigures its identity from a forgotten relic into a vital civic institution, demonstrating how reuse can reshape urban value,” explains Attiq.

Learning From Climate Intelligence Through Old Buildings

From Walled City to Contemporary City: Vernacular Lessons for Modern Urbanism, a talk by Attiq Ahmed at Qatar University

When discussing climate vulnerability, Attiq is clear that solutions need not be speculative or technologically extravagant. The most urgent and achievable intervention, he argues, is to reduce energy consumption and heat production by re-engaging with vernacular climatic intelligence.

Pakistan’s historic architecture, across both rural and urban contexts, offers a sophisticated repertoire for managing heat, humidity, and rainfall. Courtyards, thick walls, material mass, shaded thresholds, and passive ventilation systems were developed over centuries of lived experience. Reclaiming and reinterpreting these strategies, Attiq believes, presents a realistic pathway toward climate resilience without sacrificing contemporary architectural expression.

Building Responsibly Within Economic Realities

Economic constraints, Attiq acknowledges, are an unavoidable reality of architectural practice. His response, however, is not to scale back ambition, but to rethink priorities. His practice begins with staying as local as possible, whether in materials, craftsmanship, or even hardware. In Lahore, this often means working with Lahori brick and regionally sourced elements, embedding local economies and skills directly into the architecture.

At the same time, passive environmental performance is integrated into the design process from the outset. Drawing from historic precedents, buildings are designed to perform climatically rather than relying on energy-intensive systems.

Crucially, Attiq insists that this does not mean producing architecture that looks backward. His work remains unapologetically contemporary, proving that responsibility and modernity are not opposing forces.

Shifting Mindsets, Not Just Materials

If there is one mindset Attiq believes must change to enable climate-responsive cities, it is the assumption that climate damage is inevitable and irreversible. Without challenging this belief, he argues, architectural and urban practices remain trapped on a trajectory toward catastrophe, well beyond the already breached 1.5°C threshold.

A collective recognition that spatial habits matter that how we move, build, and occupy cities has real climatic impact is essential. Only with this understanding, Attiq stresses, can cities begin to mitigate, and perhaps even reverse, some of the damage already underway.

Lessons From Middle East: Ambition and Caution

Reflecting on the evolving urban models of the Middle East, Attiq acknowledges the region’s role as a laboratory for ambitious architectural and urban experimentation. Projects such as Dubai’s Loop and its zero-carbon ambitions illustrate what is possible when political will aligns with design innovation.

Yet the most instructive lesson for Pakistan, he cautions, is not scale or spectacle, but restraint. Rapid urbanisation across the Middle East demonstrates both promise and peril, particularly when development remains car-centred and sprawling. Pakistan, Attiq argues, must resist repeating these patterns. Instead, it should cultivate compact, less automobile-dependent urban environments that prioritise walkability, density, and public life.

Why Platforms Like Qatar Museums Matter

Within this framework, Attiq underscores the importance of dialogues such as those initiated by QM’s new programme: Architecture and Design: Turning Vision Into a Universal Dialogue. These platforms, he believes, are invaluable precisely because they bring together diverse regional and international voices in shared spaces of exchange.

Within this framework, Attiq underscores the importance of dialogues such as those initiated by QM’s new programme: Architecture and Design: Turning Vision Into a Universal Dialogue. These platforms, he believes, are invaluable precisely because they bring together diverse regional and international voices in shared spaces of exchange.

“Such conversations allow for unexpected connections to emerge, between contexts, climates, and practices, and create conditions for genuinely generative thinking. Rather than prescribing solutions, these dialogues provoke new questions, seed alternative modes of practice, and challenge architects to think beyond their immediate geographies,” he says.

The City and the Car

When pressed to name one urgent change cities must make to survive the climate crisis, Attiq’s answer is unequivocal: we must dramatically reduce our reliance on automobiles. While cars cannot be eliminated entirely, cities can, and must, be planned in ways that render them unnecessary for most daily life.

He points to cities such as New York and London, where diminishing the centrality of the car has become fundamental to creating resilient and liveable urban environments. For Attiq, this shift is not merely infrastructural, but cultural. Reducing car dependence reshapes how people experience distance, time, and public space, and is central to any serious climate-responsive urban future.

Architecture as Choice

Across Attiq’s reflections runs a consistent thread: architecture is never neutral. Every material selected, every street widened or narrowed, every building demolished or reused contributes to a broader spatial and environmental trajectory. His participation in Qatar Museums’ Architectural Programme situates these concerns within a wider regional dialogue, one that recognises shared vulnerabilities while respecting local specificity.

Across Attiq’s reflections runs a consistent thread: architecture is never neutral. Every material selected, every street widened or narrowed, every building demolished or reused contributes to a broader spatial and environmental trajectory. His participation in Qatar Museums’ Architectural Programme situates these concerns within a wider regional dialogue, one that recognises shared vulnerabilities while respecting local specificity.

In a moment when climate thresholds have already been crossed, Attiq does not offer easy optimism. What he offers instead is clarity: that the future of cities will be shaped not by inevitability, but by intention. And that architecture, when grounded in memory, responsibility, and collective will, holds the capacity to alter the future.

All Images Courtesy Qatar Museums