Remembering Charles Correa

On the 90th birth anniversary of Charles Correa, Bijoy Ramachandran, Founder, HundredHands writes about the influence that the works of this architect whom RIBA declared as “India’s greatest architect” had on his life and practice.

Kovalam Beach Resort in Trivandrum: Correa incorporated the local wisdom of natural ventilation and to preserve the natural beauty of the site, the facilities were all built into the hill slopes. The construction is entirely in the traditional style of Kerala—white plastered walls with red-tiled roofs. A Correa master-piece.

Growing up in boarding school in the 80s, I remember vividly my summer vacations with my grandparents in Trivandrum and our drives down to Kovalam to visit the beach. These trips almost always included fried fish at the Ashok and a dip in that amazing pool from where one saw the beaches below and the vast horizon beyond. This building was my introduction to Charles Correa and modern Indian Architecture. Unlike anything I had seen before and yet familiar, obvious and in some sense inevitable – a series of terraces on a hill from where to survey the oceans. Moving from the intimate, nestled interior embedded in the rock, a place of refuge; out to the brazen, sun drenched terrace, a place of prospect. What a beautiful idea!

Ismaili Centre, Toronto, 2014 was Correa’s last work and is an architectural interpretation of Islam.

As a student of architecture, Correa’s projects and his essays helped me navigate this new world which at once seemed both tangible, real and indescribable and ephemeral. Correa’s essays were accessible – making connections between architecture and art, music, and literature on the one hand and climate, society, and aspirations on the other. They helped me understand the fundamental concerns of this practicing professional and how he saw his place in the world. They illustrated basic ideas informing architectural strategies and maneuvers (the open to sky space, the ritualistic pathway, the tube house/summer/winter sections, etc.) but also located these within larger narratives of mythology, metaphysics and deep structure, a term he often used.

- Kanchenjunga Apartments, Mumbai, 1983: One of the luxurious apartment blocks in India, the minimalist design was used by Correa to open up to the apartments to the sea and the winds.

These larger ideas continue to require reflection and Correa’s ability to summon this ‘deep structure’, the quality of stillness and humility in Ahmedabad, a sense of the ephemeral and the great beyond in Lisbon, or the comfort of a quiet refuge in Bangalore continue to inspire our own ambitions and challenge us to consider more fundamentally what our work is about. With his companion texts and simple, clear illustrations and diagrams the underpinnings of his buildings were revealed. Buildings as ideas or rather ideas as buildings.

The Champalimaud Centre for the Unknown comprises two buildings, the first containing research laboratories, and treatment rooms, and the second housing an auditorium and exhibition area. The building is seen as a sculpture and in Correa’s own words, ” Architecture as Sculpture. Architecture as Beauty. Beauty as therapy.”

To me as a practitioner now, Correa’s work and practice offer one other rather revolutionary idea. And this has to do with the nature of his practice and the way he chose to engage with the world. Practice as idea or idea as practice.

In many ways he predated by many decades what is now called the ‘radical’ architect, based on Justin McGuirk’s recent book, ‘Radical Cities’- the activist/architect or pragmatist who isn’t waiting for the public authorities to initiate public works (housing, infrastructure, planning etc.) but is finding new ways to define and implement projects, like this year’s Pritzker awardee, Alejandro Aravena.

“Architecture is not a moveable feast, like music. You can give the same concert in three different places, but you can’t just repeat buildings and clone them across the world.”

“Architecture is not a moveable feast, like music. You can give the same concert in three different places, but you can’t just repeat buildings and clone them across the world.”

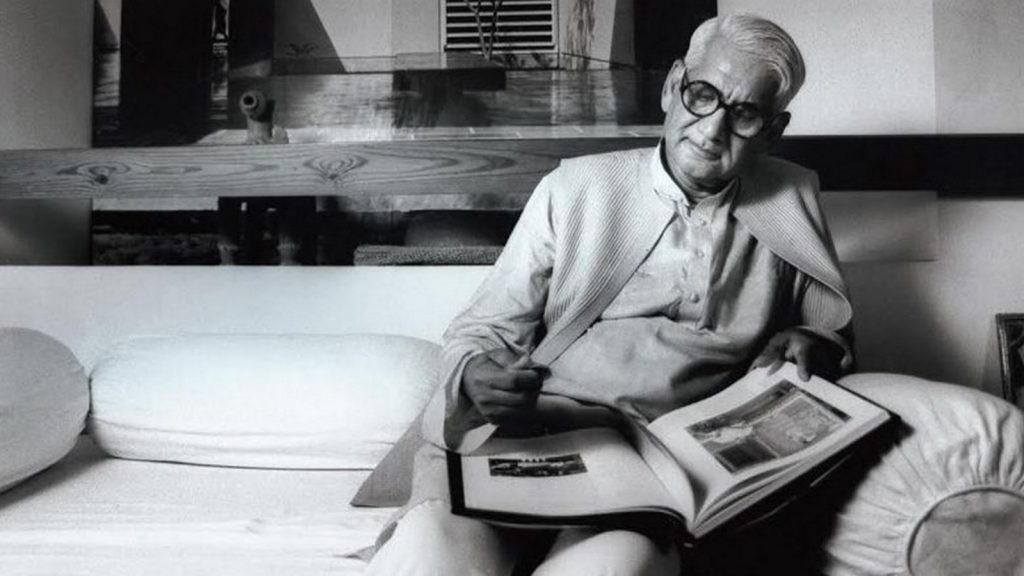

Charles Mark Correa

Correa was involved in this sort of proactive architecture and master planning throughout his career. His work on the proposals for New Bombay, the mill lands, the vast portfolio of public housing projects and town plans are inspirational. This active concern for the public realm, housing, infrastructure, and the image of the city is a real lesson for me as a practitioner. Correa did not wait for the commission, the invitation – he was out there writing, drawing, making presentations with an urgency that seems just incredible now.

Gandhi Memorial Museum (and residence): To reflect the simplicity of Gandhi’s life and the incremental nature of a living institution, the architect used modular units 6 meters x 6 meters of reinforced cement concrete connecting spaces, both open and covered, allowing for eventual expansion.

Correa wrote, “Architecture is an agent of change…which is why a leader like Mahatma Gandhi is called the architect of the nation. Neither the engineer, nor the dentist, nor the historian. But the architect, the generalist who speculates on how the pieces could fit together in more advantageous ways. One who is concerned with what might be.”

Jawahar Kala Kendra in Jaipur, 1993 is built to mirror the structure of the city itself, and is an example of how Correa’s buildings have always been with respect to context.

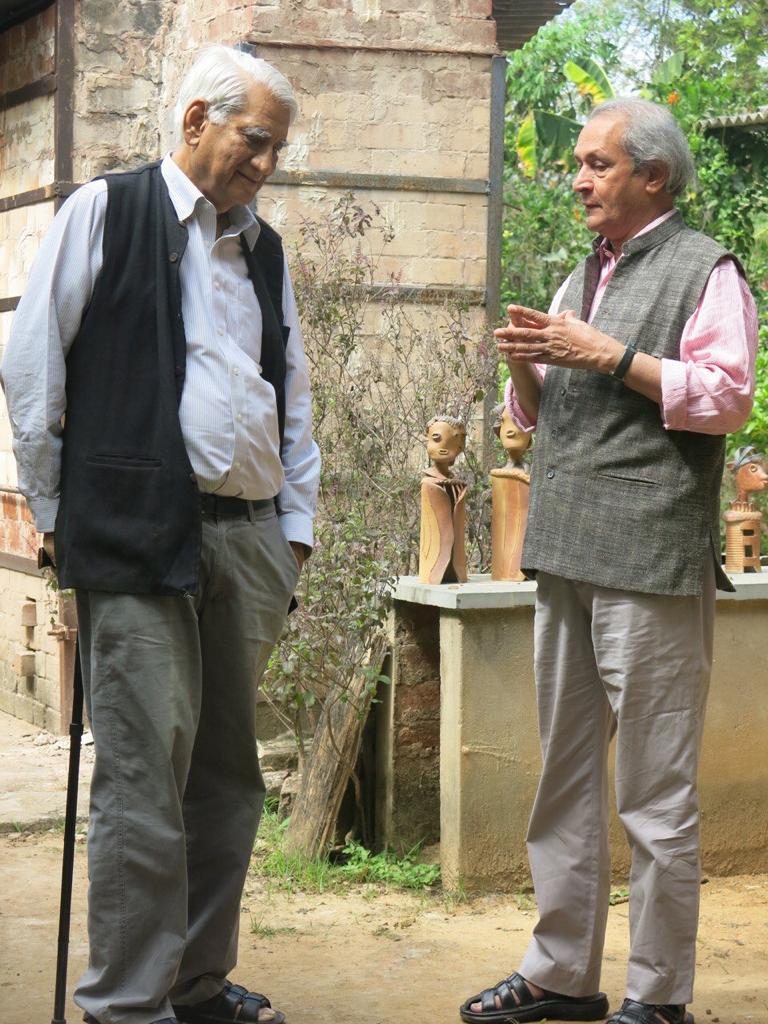

The author, architect Bijoy Ramachandran with Correa on their Bangalore visit, with Femina Rahman and Chirag Jain (from the Vimal Jain Foundation).

In November 2014, Monika and Correa visited us in Bangalore. We organised a conversation with Dr. Jyotindra Jain at the Indian Institute of Science. As a result of this, I had the great good fortune of spending 5 days with them, ferrying them all over the city, Bangalore’s infamous traffic jams now working in my favor offering me more time for conversation! It was a magical five days. Though down with a rather severe throat infection, Correa constantly discussed the city, our role as architects, the nature of this new foundation we had set up, its focus…every discussion was detailed, thought-provoking, and intense. It was incredible to be in the company of someone so engaged, curious, and genuinely interested in the world. Correa’s buildings, the seminal ideas they represent and his relentless engagement with the betterment of the world around him inspires me to be a better architect and a more sensitive human being.

(Sourced from Celebrating Charles Correa / State of Architecture Exhibition, Mumbai January 2016)

Last two images: Courtesy Bijoy Ramachandran.