we refuse_d at Mathaf: Collective Acts of Refusal

As Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art marks its 15th anniversary, the museum positions itself once again as a space for critical dialogue and the rethinking of modern and contemporary art from the Arab world. Among the two major exhibitions unveiled for this milestone season is we refuse_d, a project that brings together more than 15 contemporary artists whose practices confront silencing, censorship, displacement, and erasure. SCALE talked to the curators of we refuse_d, Nadia Radwan and Vasıf Kortun to understand how collective practice and unwavering political stance becomes the exhibition’s most powerful statement.

we refuse_d, presented alongside Resolutions: Celebrating 15 Years of Mathaf, forms part of a broader institutional reflection on memory, resistance, and the role of cultural spaces in moments of global precarity. The exhibition is ongoing at Mathaf till February 8, 2026.

Work of Samia Halaby’s abstract compositions are rooted in a deep engagement with movement, rhythm, and visual perception, often inspired by natural forms, urban landscapes, and the geometry of traditional Islamic art. Pic Courtesy Qatar Museums

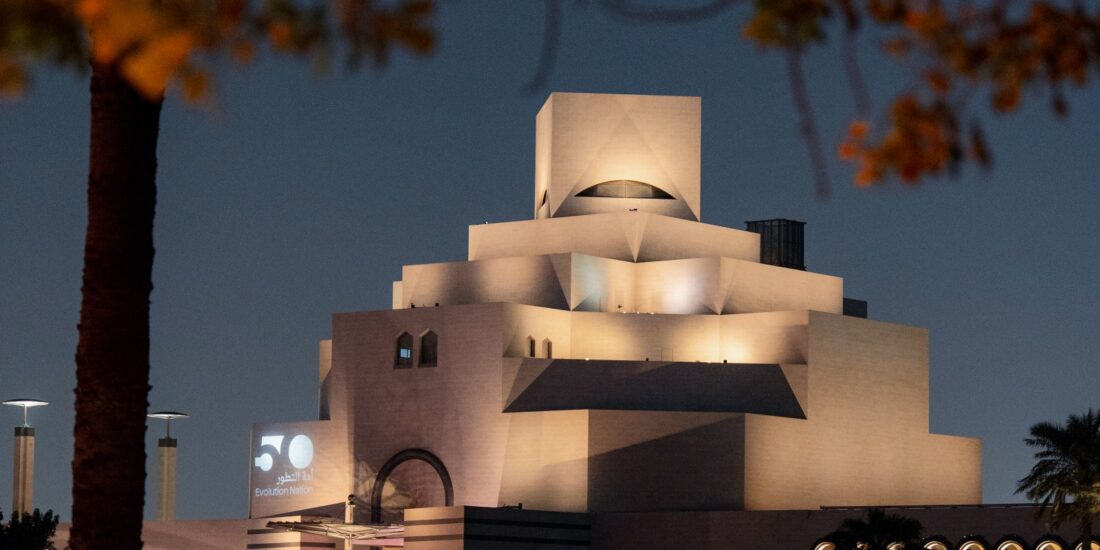

Together, these exhibitions reaffirm Mathaf’s role as a platform for artistic agency and scholarship, situated within Qatar’s larger cultural vision under the Evolution Nation campaign.

Curated by Nadia Radwan and Vasıf Kortun, we refuse_d is not structured as a thematic exhibition in the conventional sense. Instead, it operates as a constellation of material, political, poetic, and ethical, each emerging from lived experience. Refusal, here, is not a singular gesture. It is a multiplicity of strategies, some loud while some are quiet and some barely visible, say the curators.

The artistic research practice of DAAR (Decolonising Architecture Art Research), founded by Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti, operates at the intersection of architecture, art, pedagogy, and politics. Pic Courtesy Qatar Museums

According to the curators, the exhibition responds to an escalating wave of cancellations, censorship, silencing, and public vilification directed at artists, writers, musicians, and scholars who have taken clear and often courageous stances on war, conflict, and uprisings.

More recently, in the context of the war on Palestine, many have chosen to withdraw from exhibitions and cultural events-often at significant personal and professional cost. In such a climate, the act of making art becomes both a gesture of presence and an act of refusal.

“We were not being heroic, defiant or opportunistic but merely making an exhibition that is relevant and timely,” say the curators, “We believed it was essential to claim the exhibition’s agency and to exploit its potential as a form of speech not reduced to dictation or recipes. It may be apt to pose questions to numerous institutions worldwide and ask, “What have you done when…?”

Nadi Radwan and Vasif Kortun, Curators of we refuse_d. Pic Courtesy Qatar Museums

Nadi Radwan is an art historian and curator specialising in Middle Eastern modernism, currently serving as the head of Visual Arts at HEAD, Geneva and founder of the Manazir platform for visual arts in the MENA region.

Vasıf Kortun is a Turkish curator and writer, best known as the founding director of SALT and Platform Garanti in Istanbul, and for curating the 3rd and 9th Istanbul Biennials as well as the 2008 Taipei Biennial.

In conversation with SCALE, the curators reflect on how the exhibition took shape, how their understanding of refusal evolved through the process, and how collective practice and unwavering political stance became the exhibition’s most powerful statement.

On Selecting the Artists and the Emergence of a Collective Logic

The notion of displacement, both political and philosophical, is central to Khalil Rabah’s work. By incorporating materials such as olive trees, soil, and stone, Rabah situates these symbols of resilience and rootedness within globalised art institutions, emphasising their forced dislocation. Through his archives and artifacts, he proposes fragmented, subjective counter-histories that resist official erasures. Pic Courtesy Qatar Museums.

When asked about how the 15 artists were selected and what connected their varied practices, Radwan and Kortun emphasised that the process was not pre-scripted, but rather emerged through dialogue and relational thinking:

“The selection of artists developed collectively and organically, shaped by ongoing conversations we had with them. These exchanges were guided by shared commitments and a specific need to present positions that confront the immediacy of the present with diverse approaches. We realised later that the selection also highlighted that most of the artists are engaged in networks of solidarity; they are also cultural workers, founders of alternative spaces, educators, researchers, and thinkers. There were pathways such as persistence, resistance, heritage, community, and repair. We sought an intergenerational group of artists born between 1936 and 1991, and how their engagement shaped across generations, contexts, and lived experience. Some of them have personally faced loss, displacement, and silencing,” say the curators.

Samia Halaby is widely recognised as one of the most important figures in contemporary Arab art and her work is part of we refuse_d.

Rather than framing refusal as a theme imposed upon the works, the curators allowed it to emerge as a shared condition, one that unfolded through histories, and lived realities.

The Many Forms of Refusal

Work of DAAR at Mathaf. Pic Courtesy Qatar Museums.

One of the exhibition’s most compelling aspects is its insistence that refusal is not a singular act. It can be loud or quiet, visible or withdrawn, embodied or abstract. Asked how these different modes manifested across the participating artists, the curators responded:

“Refusal comes in multiple forms. DAAR refuses the ‘discourse of suffering’ and ‘humanitarian concern’ typically applied to refugees, and instead asserts refugee camps as sites of ‘social and cultural production’ by formulating the concept of ‘refugee heritage’ to challenge conventional understanding of heritage.”

The artistic research practice of DAAR (Decolonising Architecture Art Research), founded by Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti, operates at the intersection of architecture, art, pedagogy, and politics. Central to their practice is Campus in Camps, an experimental university in a refugee camp that redefines who produces knowledge and where. This commitment to informal, community-based learning continues through The Tree School developed across various locations worldwide. DAAR’s work consistently connects to local struggles with global questions of justice and demonstrates how architecture and art can propose and inhabit alternative narratives and spaces.

Samia Halaby’s work at Mathaf. Pic Courtesy Qatar Museums.

“Samia Halaby’s retrospective was famously cancelled. She refuses the binaries of East and West and of nationalist and universalist discourses, claiming abstraction as a visual language grounded in social struggle,” says Nadia Radwan.

“Walid Raad and Pierre Huyghebaert’s installation offers a meta-commentary on refusal, highlighting how institutions employ mechanisms of power.”

Grounded in a deep engagement with Palestinian embroidery (tatreez), Nour Shantout’s work treats this traditional craft not merely as heritage, but as a living, resistant archive, one that embodies identity, counter-memory, and intergenerational knowledge. Pic Courtesy Qatar Museums

“Nour Shantout, who faced a traumatic cancellation, responds to censorship by ‘revealing less.’ She paradoxically uses pixelation to assert presence and agency,” explains Kortun.

Taysir Batniji presents a selection of works centred on the motif of keys, objects he has explored from the 1990’s as powerful metaphors for dispossession and displacement. These works evoke the immobilisation Palestinians face in their daily lives, and the inability to control or shape space and time. Pic Courtesy Qatar Museums

“Taysir Batniji’s refusal manifests as poetic restraint and silence born of trauma. He refuses overt political statements in favour of the everyday and ephemeral, using silence as a material that speaks to the inability to control or shape space,” says Radwan.

Prompted by the urgency of the violence in Palestine, Dima Srouji’s approach investigates the architectural “what-ifs”: unrealised historical plans, abandoned structures, and speculative designs that gesture toward alternative futures. Pic Courtesy Qatar Museums

Majd Abdel Hamid refuses the noise of the current moment; his work ‘does not shout but instead insists on calm, focused attention,’ acting as a ‘meditative resistance.’ He traces the life of a succulent plant, using its biological ability to survive in ‘scarce resources’ as a material symbol of refusal to disappear.

“Oraib Toukan parts ways with the ‘polemic of cruel images’ (media coverage of violence). Her refusal is material, turning instead to the ‘grain of soil’ (turbeh) and a ‘haptic approach’ to visuals,” says the curator.

Work of Khalil Rabah. Pic Courtesy Qatar Museums.

Khalil Rabah incorporates living materials, such as olive trees, into the institution to emphasise ‘forced dislocation.’

These refusals, taken together, form a landscape of strategies, some grounded in silence, others in abstraction, others in care, materiality, and presence.

When Artists Reshape the Curatorial Frame

Rather than presenting overt political statements, Taysir Batniji turns to the everyday, the overlooked, and the ephemeral to reflect on the effects of loss, and fragmentation.

Rather than treating the exhibition as a fixed conceptual structure, the curators allowed themselves to be reshaped by the artists’ propositions. When asked whether specific works altered their understanding of refusal, they answered:

“The best artists offer perspectives that are not limited to the dictates of the exhibition or broaden the dictates by engaging with them in unexpected ways. The best art is always more than what it offers. We would not want to single out anyone, but yes, our understanding of refusal itself was transformed by the process. We as curators, are also part of the audience after the exhibition opened. It is a learning process,” they said.

For Barış Doğrusöz’s work INTERSTICES (a dizzying array of combinations), he reimagined installation Interstices, a dizzying array of combinations (2018), composed initially of 45 abstracted sculptures based on the form of pillboxes, with small apertures for weapons commonly found across Lebanon, Palestine, and conflict zones near sensitive targets like official buildings or interstitial sites like checkpoints. These structures are specifically designed to be invisible or impenetrable in their form while also constructing the boundaries or borders of access.

This idea, that curators, too, become learners, undercuts the hierarchical structure often associated with institutional exhibitions.

Personal Voices and Collective Statements

Work of Noura.

One of the challenges in collective exhibitions is negotiating the tension between individual narratives and overarching frameworks. Yet Radwan and Kortun describe this not as a conflict, but as a generative alignment:

“We do not believe there was a tension between the personal narratives and the curatorial frame. On the contrary, we feel a sense of alignment and synergy. The only dynamic tensions were between forms of refusal, endurance, and action, and that is needed,” they state.

Presenting acts of refusal within an institutional setting always raises ethical questions. How does a museum host resistance without neutralising it? The curators were clear about Mathaf’s role in this process:

“Mathaf, and, by extension, Qatar, has been grounded in a commitment to solidarity and to reasserting artistic agency. It validated the refusal to ‘disappear’ or to ‘be refused’ as a necessary ethical act. The exhibition initially evoked the spirit of the Salon des Refusés to position the institution as a space for critical engagement outside the discourses of power. The artists would not otherwise accept participating,” they countered.

Here, the institution is not merely a container but an active participant in the ethics of display.

Fragile Optimism

For we refuse_d, Barış Doğrusöz expanded the installation with newly produced sculptures, informed by updated research and architectural military artifacts that reflect post-war developments in Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria.

Asked to define the “fragile optimism” of the exhibition through a single work or moment, the curators pointed to one gesture that quietly carries the exhibition’s emotional core:

“The artwork that best defines literally ‘fragile optimism’ is Majd Abdel Hamid’s tracing of a succulent’s life. The succulent is a plant that thrives in ecosystems with scarce resources, is relevant to the context of displacement and precarity, and reverberates with life. It embodies the exhibition’s theme by tracing survival and repair in an artisanal and unpretentious manner. However, we feel that a fragile optimism cuts through each work.”

Perhaps the most revealing insight emerged when the curators reflected on how the process reshaped their own understanding of refusal, resistance, and persistence. They noted that every meaningful exhibition is also a space for learning, introspection, and the possibility of shifting one’s own perspective. This transformation, they explained, is deeply personal. They are no longer the same people they were when they first began imagining the exhibition, even though the act of curating itself is intentional and carefully considered.

we refuse_d

They also spoke about the profound difference between encountering a work online and experiencing it in physical proximity to other works, how meaning changes when artworks enter into dialogue with one another. For them, receiving propositions from artists that go beyond their initial expectations is something to be celebrated. While curators may hold a certain agency, they emphasised that it is ultimately the artists who make the exhibition.

“This is why selecting just one or two works feels impossible: the strength of we refuse_d lies in its collective voice,” reiterate Nadia Radwan and Vasıf Kortun.