Agapecasa Re-edits the Schwob Table

In Paris, during Maison&Objet 2026, Agapecasa unveils the re-edition of a rare and previously unreleased design: the Schwob Table, originally conceived in 1958–59 by Angelo Mangiarotti and Bruno Morassutti. Presented at Silvera, the debut unfolded within an installation curated by Agapecasa and Silvera, with a spatial project by architect Camilla Benedini, developed in conjunction with Maison&Objet.

More than the unveiling of a collectible object, the re-edition marks the recovery of a missing piece within Mangiarotti’s public narrative, one that reconnects furniture, architecture, and historical context into a single, coherent lineage.

More than the unveiling of a collectible object, the re-edition marks the recovery of a missing piece within Mangiarotti’s public narrative, one that reconnects furniture, architecture, and historical context into a single, coherent lineage.

Originally designed for the interiors of Villa Schwob, also known as Villa Turque, the table was produced in only a handful of examples and never entered industrial production. Its existence endured through photographs, drawings, and archival accounts. Today, Agapecasa presents a philological re-edition, faithful in proportions, materials, and constructive logic, making accessible a project tied to an unrepeatable moment in twentieth-century architectural culture.

A Moment of Convergence

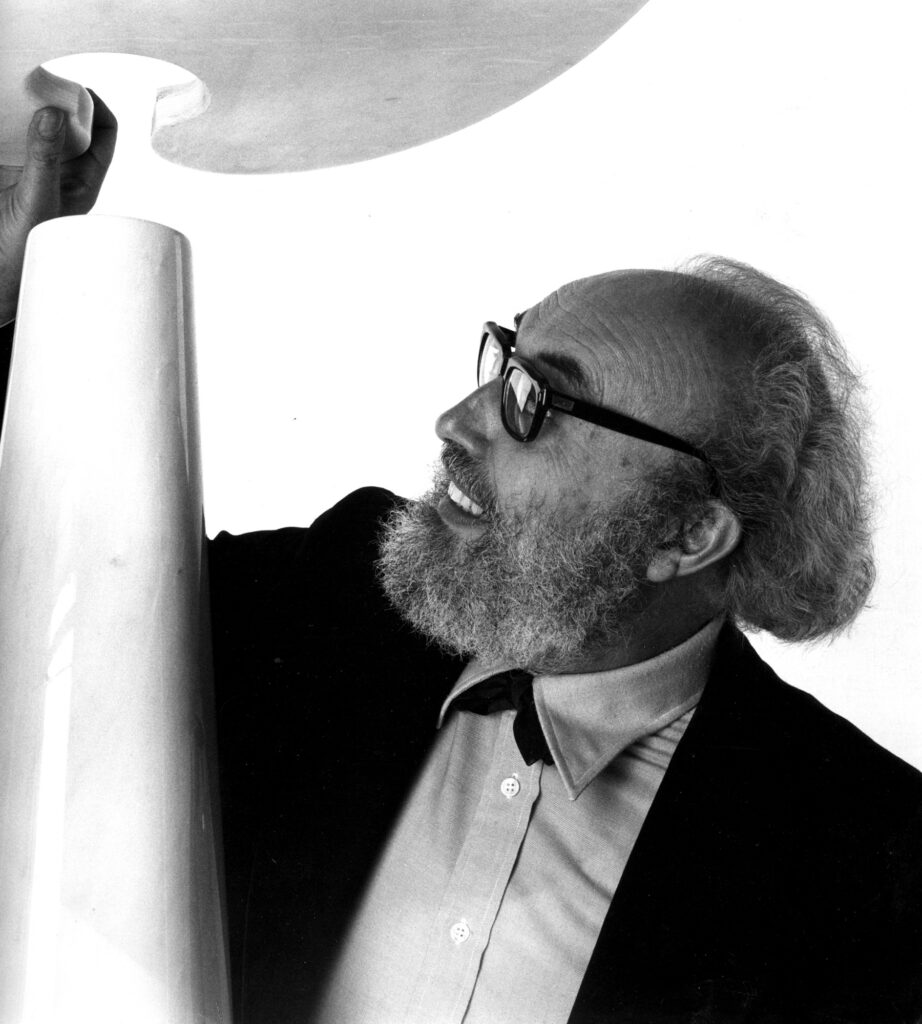

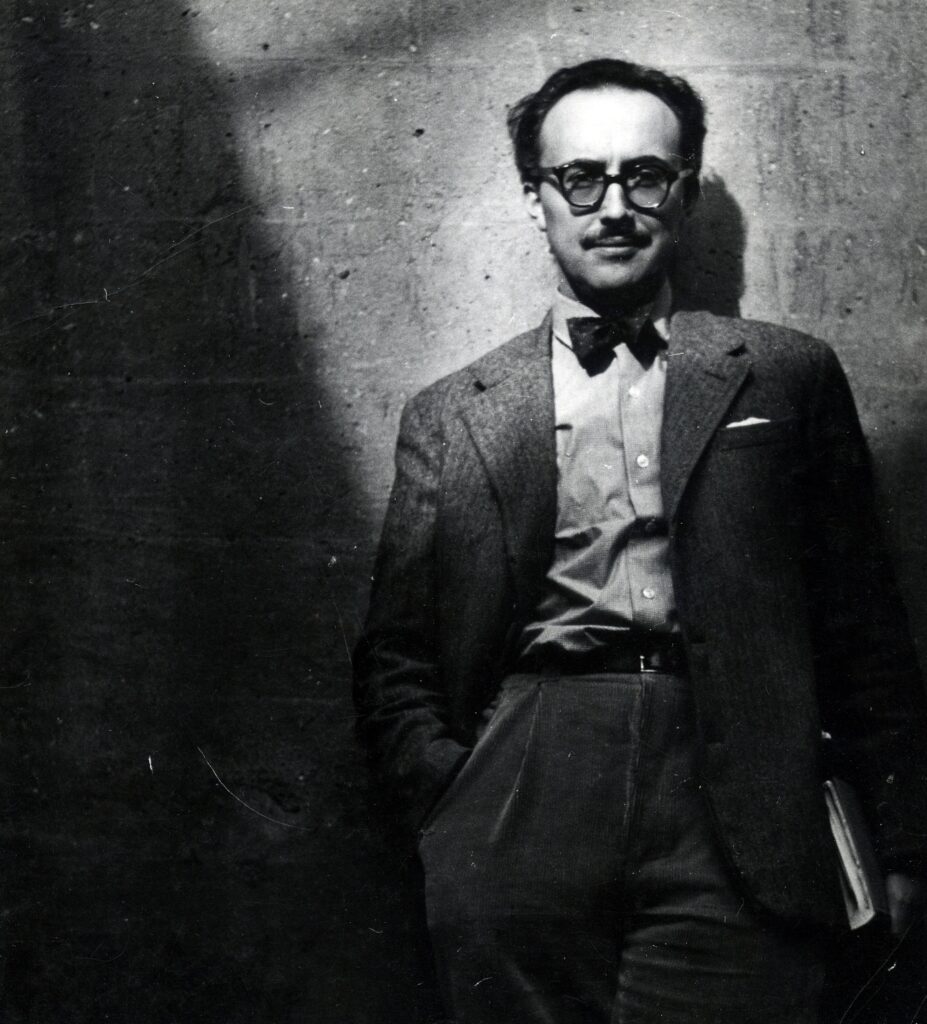

Angelo Mangiarotti

Built between 1916 and 1917 for entrepreneur Anatole Schwob, Villa Schwob represents a pivotal threshold in the work of Le Corbusier. It was the last major work of his Swiss period, already gesturing toward the abstract geometry, structural use of concrete, and spatial engagement with light that would define his later purist phase.

When Mangiarotti and Morassutti were invited, four decades later, to reinterpret the villa’s interiors, they approached the commission with deliberate restraint, preserving the power of the original layout while introducing elements aligned with the material culture and structural thinking of the 1950s.

Image of Angelo Mangiarotti

It is precisely at this point of convergence, between early modernism and post-war architectural reasoning, that the Schwob Table was conceived.

The table emerged from a brief yet intense period of shared practice between Mangiarotti and Morassutti in Milan, when architecture, interiors, and furniture were approached as a single integrated system. As Agapecasa notes, the table originates from a “discreet but extraordinarily dense site, where ideas, methods, and sensibilities briefly overlapped”, a hidden gem, both architecturally and culturally.

A Missing Piece in Mangiarotti’s Narrative

For Agapecasa, what drew them to the Schwob Table was precisely its absence from the broader understanding of Mangiarotti’s work. Conceived for a specific architectural context, rigorously designed, built, and used, the table had never been absorbed into his public body of work.

For Agapecasa, what drew them to the Schwob Table was precisely its absence from the broader understanding of Mangiarotti’s work. Conceived for a specific architectural context, rigorously designed, built, and used, the table had never been absorbed into his public body of work.

Preserving a legacy, they explain, does not mean repeating icons. Instead, it involves restoring coherence where history has left fragments. The Schwob Table does not add something new to Mangiarotti’s oeuvre; rather, it restores a missing element, one that clarifies his thinking on structure, gravity, and proportion. In this sense, the table is not an exception but a key, allowing other works to be read more clearly.

Preserving a legacy, they explain, does not mean repeating icons. Instead, it involves restoring coherence where history has left fragments. The Schwob Table does not add something new to Mangiarotti’s oeuvre; rather, it restores a missing element, one that clarifies his thinking on structure, gravity, and proportion. In this sense, the table is not an exception but a key, allowing other works to be read more clearly.

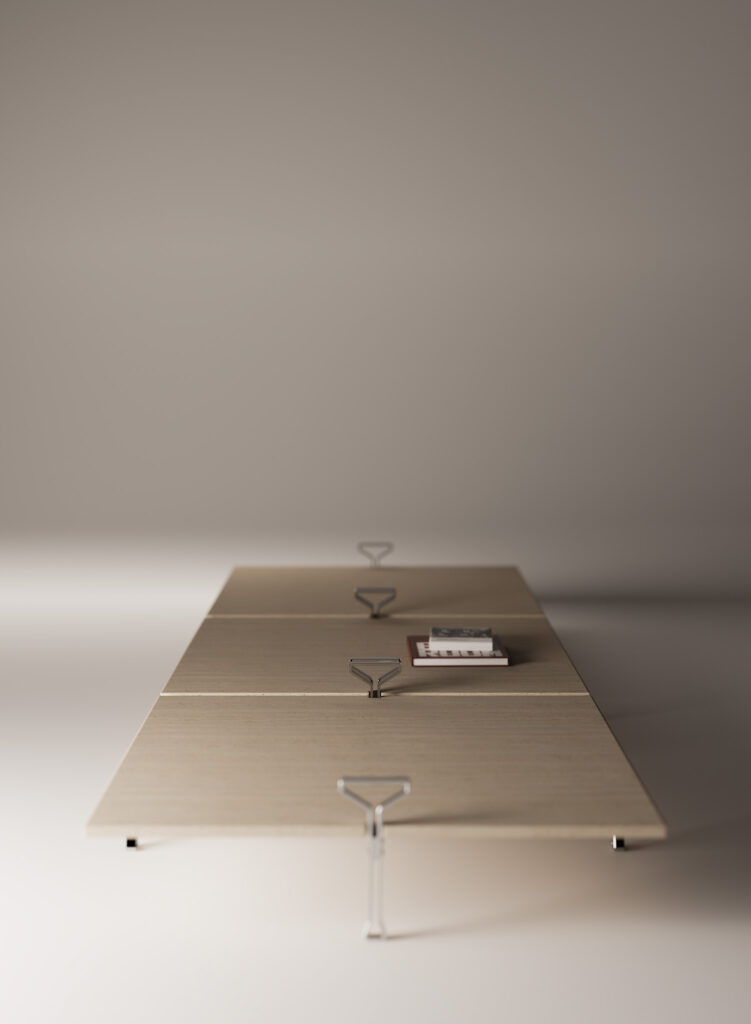

Mechanical Essence, Spatial Measure

The Schwob Table was conceived for the villa’s large double-height hall, a space dominated by a monumental window and a sculptural axis. Within this setting, the table introduces a modular horizontal landscape, supporting spatial continuity while allowing the eye to remain free toward the exterior.

The Schwob Table was conceived for the villa’s large double-height hall, a space dominated by a monumental window and a sculptural axis. Within this setting, the table introduces a modular horizontal landscape, supporting spatial continuity while allowing the eye to remain free toward the exterior.

Its design is governed not by decoration but by structural reasoning. Integrated side handles—resolved as part of the table’s load-bearing logic—facilitate movement while transforming a functional necessity into a recognisable architectural sign. Here, gesture and structure coincide.

Furniture as Micro-Architecture

Presented alongside other works from the Mangiarotti Collection, including the Eros table, Tre3 chairs, the Cavalletto system, and CAP53 vases, the Schwob Table reveals a continuity that transcends decades.

Presented alongside other works from the Mangiarotti Collection, including the Eros table, Tre3 chairs, the Cavalletto system, and CAP53 vases, the Schwob Table reveals a continuity that transcends decades.

What unites these works, Agapecasa explains, is not a shared formal vocabulary but a structural ethic. Across time, Mangiarotti consistently treated furniture as architecture at a reduced scale. Elements are defined by load, balance, compression, and precise points of contact rather than by surface or style.

In the Schwob Table, as in Eros or Cavalletto, form is the visible consequence of how forces move through matter. Joints rely on gravity rather than mechanical fastening; weight itself becomes a constructive principle. Assembly is achieved through balance, not force. There is also a shared refusal of redundancy—no element exists unless it performs a task. Even joints are not added details, but moments where structure and meaning coincide. This internal logic, rather than fashion or period language, is what allows these works to continue speaking to one another across time.

The Discipline of a Philological Re-Edition

Describing the Schwob Table as a philological re-edition is not rhetorical. For Agapecasa, it means working strictly from primary sources, original drawings, proportions, materials, and construction principles, treated as non-negotiable references.

Describing the Schwob Table as a philological re-edition is not rhetorical. For Agapecasa, it means working strictly from primary sources, original drawings, proportions, materials, and construction principles, treated as non-negotiable references.

At the same time, the re-edition had to exist within contemporary standards of precision, durability, and repeatability. The challenge was not to update the design, but to translate its intelligence into today’s manufacturing reality without dilution, according to Agapecasa.

One of the most complex aspects of production was preserving Mangiarotti’s tolerance for structural risk. His designs often operate close to equilibrium, with balance and constructive tension playing an active, expressive role.

Respecting this delicate condition, while ensuring consistency in production, required extensive testing and calibration, particularly to retain the expressive tension characteristic of Mangiarotti and Morassutti’s late-1950s research.

Materials, Dimensions, and Availability

The Agapecasa re-edition of the Schwob Table is available in three sizes, 65×65 cm, 80×80 cm, and 100×100 cm, and in a curated selection of natural stones: Bianco Carrara, Nero Marquina, Carnico, Verde Alpi, Emperador Dark, and Travertine, with special materials available on request.

The Agapecasa re-edition of the Schwob Table is available in three sizes, 65×65 cm, 80×80 cm, and 100×100 cm, and in a curated selection of natural stones: Bianco Carrara, Nero Marquina, Carnico, Verde Alpi, Emperador Dark, and Travertine, with special materials available on request.

The structure is crafted in precision-machined anodised aluminium, paired with marble tops selected for both material integrity and historical fidelity.

Agapecasa, Agape, and Continuity

Agapecasa emerged as a natural extension of Agape, safeguarding the design archive of Angelo Mangiarotti and transforming it into a contemporary collection. The continuity between the two entities is expressed through their shared attention to materials, a rigorous design approach, and a vision that links architecture, space, and everyday life.

As Agapecasa succinctly reflects: re-editing the Schwob Table is about giving continuity to a shared story, one conceived for a specific place, yet imbued with a universal idea of measure, order, and the relationship between objects and space.