From Square to Octagon: Inside the Making of MIA by I.M. Pei

When the Museum of Islamic Art opened on Doha’s Corniche in 2008, it was immediately understood as a defining moment. Not only for its architecture, or as the country’s first museum dedicated to Islamic art, but as a cultural beacon that would come to shape how Qatar was perceived on the global stage. Designed by I. M. Pei, the museum came to symbolise Qatar’s cultural ambition, architectural intent, and long-term vision.

The exhibition I. M. Pei and the Making of the Museum of Islamic Art: From Square to Octagon and Octagon to Circle, jointly organised by MIA, the Art Mill Museum, and ALRIWAQ, revisits this story with fresh depth, drawing on newly revealed archival material and curatorial research, and is ongoing till February 14, 2026.

The exhibition I. M. Pei and the Making of the Museum of Islamic Art: From Square to Octagon and Octagon to Circle, jointly organised by MIA, the Art Mill Museum, and ALRIWAQ, revisits this story with fresh depth, drawing on newly revealed archival material and curatorial research, and is ongoing till February 14, 2026.

Curated by Zahra Khan and Aurélien Lemonier, in close collaboration with the Museum of Islamic Art, the exhibition forms part of a pair of landmark presentations unveiled by Qatar Museums in October 2025, alongside I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture at ALRIWAQ .

Building an Institution, Not Just a Building

From the outset, Khan explains, the curatorial priority was to tell “the story of an institution”, not merely the story of an iconic structure. In this context, “institution” encompassed multiple parallel narratives: the architectural design, the formation of the collection, and the vision that would later shape Qatar’s broader museum ecosystem.

From the outset, Khan explains, the curatorial priority was to tell “the story of an institution”, not merely the story of an iconic structure. In this context, “institution” encompassed multiple parallel narratives: the architectural design, the formation of the collection, and the vision that would later shape Qatar’s broader museum ecosystem.

The Museum of Islamic Art, she notes, laid down an early benchmark of excellence, not only through its collaboration with Pei, but through the seriousness with which architecture, collections, and curatorial intent were developed together. This approach, she suggests, set a precedent for the future museums that would open in Qatar.

This institutional lens also explains the involvement of the Art Mill Museum team. As a museum with a strong architectural and design focus, AMM entered the project through Lemonier’s role as Senior Curator of Architecture and Gardens, with Khan, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, joining as co-curator to develop the exhibition collaboratively.

This institutional lens also explains the involvement of the Art Mill Museum team. As a museum with a strong architectural and design focus, AMM entered the project through Lemonier’s role as Senior Curator of Architecture and Gardens, with Khan, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, joining as co-curator to develop the exhibition collaboratively.

Revisiting the 1997 Architecture Competition

One of the exhibition’s most revealing sections revisits the 1997 International Architecture Competition, a chapter rarely shown publicly. Proposals by architects like Zaha Hadid and Charles Correa are included to underline the calibre of thinking involved at the project’s inception.

One of the exhibition’s most revealing sections revisits the 1997 International Architecture Competition, a chapter rarely shown publicly. Proposals by architects like Zaha Hadid and Charles Correa are included to underline the calibre of thinking involved at the project’s inception.

For Lemonier and Khan, it was essential to trace the process of the original competition.As the scope and ambition of the project evolved, the decision was made to approach Pei directly, recognising both his experience with museum designs and the depth of his architectural sensibility.

For Lemonier and Khan, it was essential to trace the process of the original competition.As the scope and ambition of the project evolved, the decision was made to approach Pei directly, recognising both his experience with museum designs and the depth of his architectural sensibility.

This moment, Khan notes, reveals the broader bold vision of the Father Emir and Qatar Museums at the time Archival materials from Geneva, shown publicly for the first time in Doha, underscore the international nature of this early process.

Searching for the “Essence” of Islamic Architecture

Central to the exhibition is Pei’s own articulation of his quest to distil the “essence of Islamic architecture.” The curators traced this search through interviews with Pei’s former collaborators, including Hiroshi Okamoto and TohTsun Lim, and through archival documents discovered during research for the parallel M+ exhibition.

Central to the exhibition is Pei’s own articulation of his quest to distil the “essence of Islamic architecture.” The curators traced this search through interviews with Pei’s former collaborators, including Hiroshi Okamoto and TohTsun Lim, and through archival documents discovered during research for the parallel M+ exhibition.

Pei’s process, Khan explains, was neither stylistic nor symbolic. Instead, it was grounded in travel, observation, and research. Over a six-month research journey, Pei visited sites across the Islamic world, from Spain and Tunisia to Turkey, India, and Egypt, encountering an architectural tradition shaped as much by climate, material, and geography as by religion.

The turning point came with his visit to the Ibn Tulun Mosque. There, Pei encountered the mosque’s sabil fountain and the progression of forms, from square to octagon to circle. that would later give the exhibition its title.

The turning point came with his visit to the Ibn Tulun Mosque. There, Pei encountered the mosque’s sabil fountain and the progression of forms, from square to octagon to circle. that would later give the exhibition its title.

“The clarity of geometry, the way light struck the surfaces, and the building’s measured spatial rhythm resonated deeply with his own architectural language,” says Khan.

To bring this process into the exhibition, the curators drew from Qatar Museums’ collection, selecting paintings, photographs, and prints depicting the sites Pei studied—such as the Alhambra and monuments in Cairo, allowing visitors to trace his visual and conceptual references.

To bring this process into the exhibition, the curators drew from Qatar Museums’ collection, selecting paintings, photographs, and prints depicting the sites Pei studied—such as the Alhambra and monuments in Cairo, allowing visitors to trace his visual and conceptual references.

Rediscovered Archives and an Unexpected Find

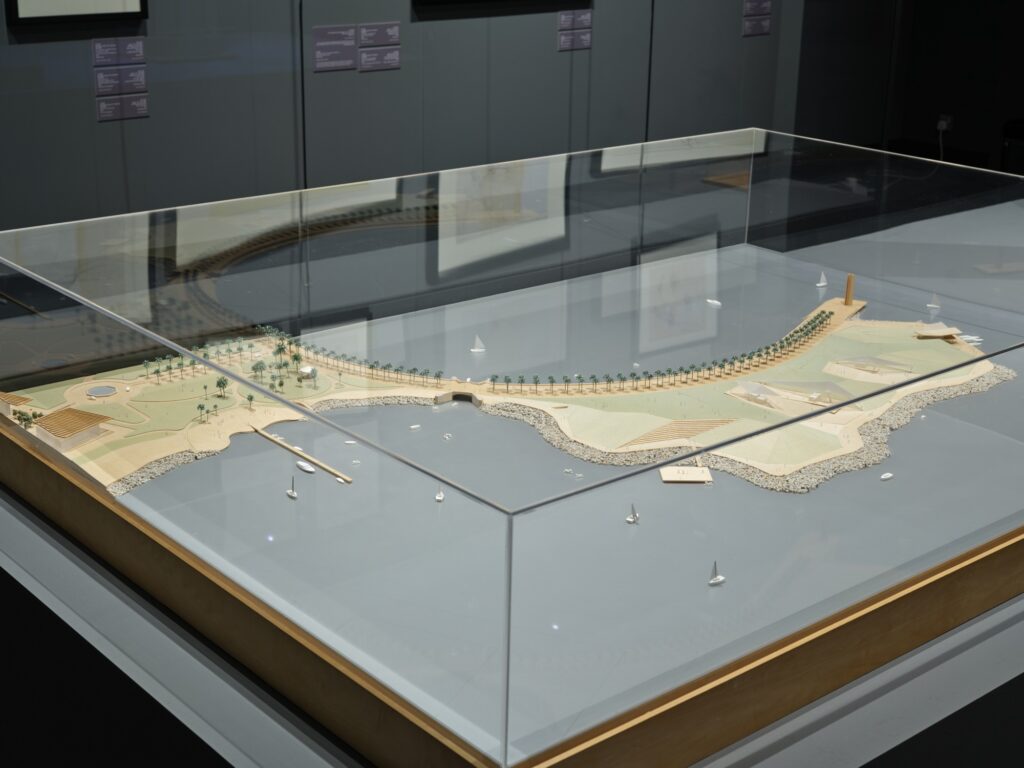

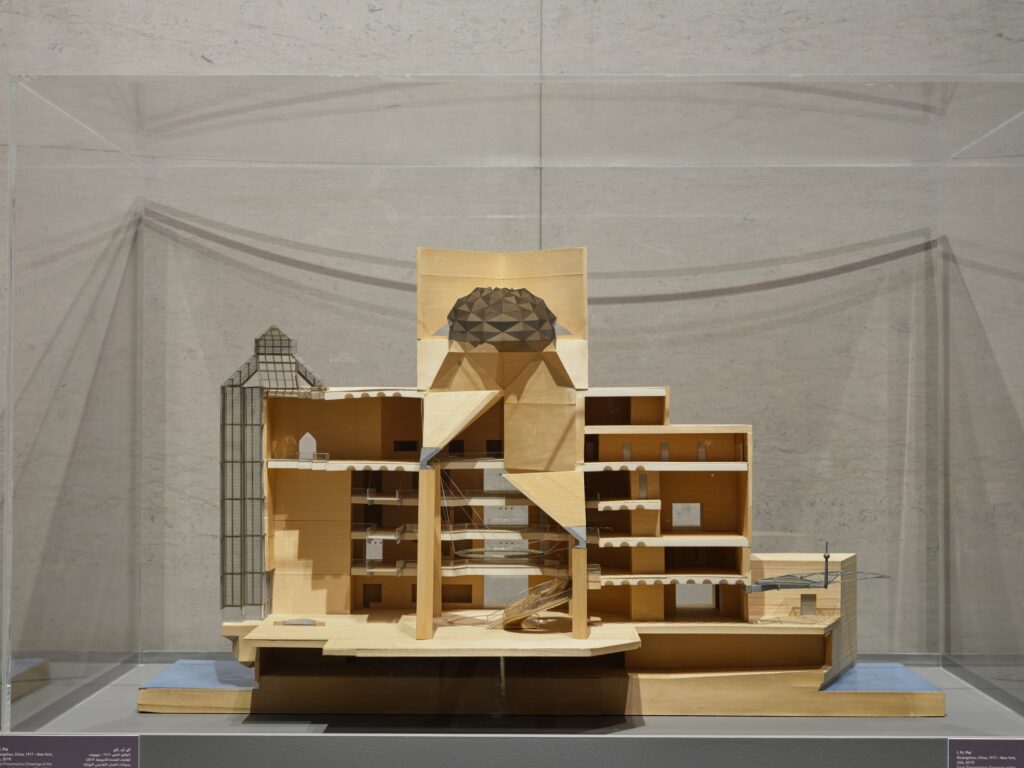

Many of the exhibition’s most striking materials, the models were rediscovered in Pei’s New York office after much of his archive had already been gifted to the Library of Congress.

Many of the exhibition’s most striking materials, the models were rediscovered in Pei’s New York office after much of his archive had already been gifted to the Library of Congress.

Khan recounts how a former associate of Pei alerted the curatorial team to models stored in the basement of Pei’s office, including studies of the MIA entrance and fountain. These were generously gifted to Qatar Museums by the Estate of I. M. Pei for the exhibition, offering rare insight into Pei’s working method. Original studies were loaned by Aslıhan Demirtaş, Aslihan, Toh Tsun, and Hiroshi, all hired by Pei to work on the MIA project.

Contrary to expectations, Pei was not a prolific sketcher. Much of his design thinking, Khan notes, was conceptual, developed mentally rather than on paper, making the surviving models and drawings all the more valuable as evidence of his process.

Architecture and Collection, Developed in Parallel

A defining curatorial decision was to weave the museum’s early acquisitions into the architectural narrative. For Lemonier and Khan, it would have been impossible to tell the story of the building without acknowledging the collection that was being assembled simultaneously.

A defining curatorial decision was to weave the museum’s early acquisitions into the architectural narrative. For Lemonier and Khan, it would have been impossible to tell the story of the building without acknowledging the collection that was being assembled simultaneously.

Objects from the museum’s earliest years, including works shown in “Silks and Ivories” at the Sheraton Hotel and later exhibitions in 2004 and 2006, were selected for their historical significance, geographic breadth, and material diversity. All date from the formative period of the museum, reinforcing the idea that architecture and collection evolved together, guided by a shared institutional vision.

While Pei’s passing meant the curators could not engage directly with the architect, they describe the process as remarkably collaborative. Pei’s former colleagues, along with MIA’s curatorial team, played a crucial role, and conversations with M+ curator Shirley Surya helped position the Doha exhibition as a focused architectural counterpart to “Life Is Architecture”.

For Khan, this project, her first exhibition in Doha since joining the Art Mill Museum—reinforced the importance of archiving, collaboration, and dialogue. It also underscored how deeply Pei considered the end user: the visitor. Every material choice, spatial decision, and architectural gesture was made with the public experience in mind.

What the Exhibition Ultimately Reveals

Visitors, Khan reflects, take away different insights: the six-month research journey, the ambition of the early competition, the precision of the models, or Pei’s humility, captured in archival footage from the museum’s opening.

Visitors, Khan reflects, take away different insights: the six-month research journey, the ambition of the early competition, the precision of the models, or Pei’s humility, captured in archival footage from the museum’s opening.

Above all, she hopes the exhibition communicates that the Museum of Islamic Art is not an empty shell, but a meticulously conceived space, built for people, shaped by history, and grounded in a vision that continues to define Doha’s cultural landscape.

All Images Courtesy Qatar Museums