Art at the Intersection of Material Science and Aeronautics

Janet Echelman creates strong wire mesh-like curtains that move with the wind creating monumental sculptures over streetscapes.

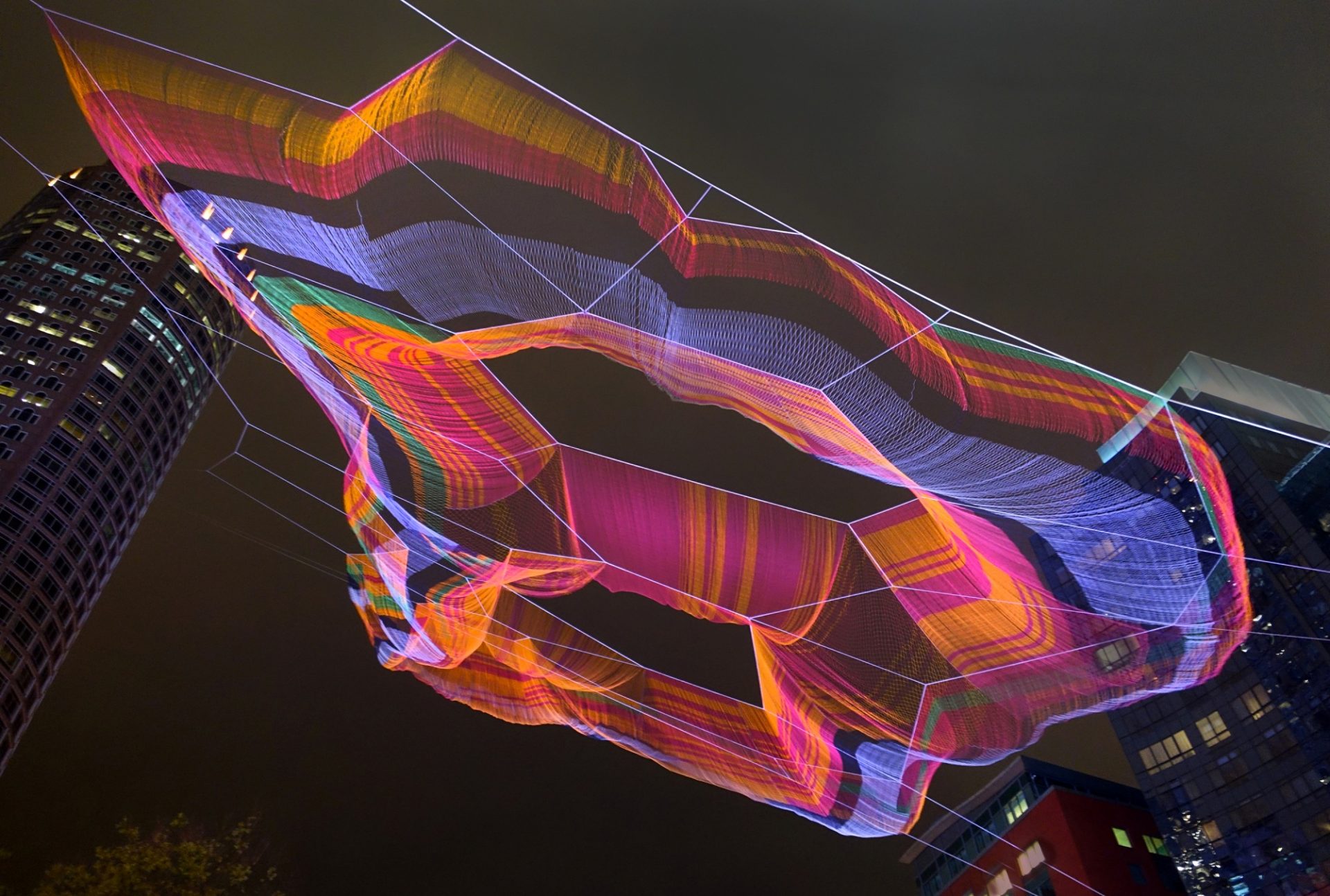

A thin net-like mirage over the cityscape in a beautiful burst of colours is the initial perception of Janet Echelman’s sculpture but soon we realise that the mirage is much more. It is an experience that transforms with wind and light, and becomes an experience you can get lost in. What is even more fascinating is how Echelman began her craft with nets. Walking through the beaches in a fishing village in South India, watching fishermen bind the net and then hurl it to the sea, Echelman was mystified and entranced by this new material. “My first satisfying sculptures were hand-crafted in collaboration with those fishermen. I brought them to the beach and lifted them into the air to photograph them. It was then that I discovered their soft surfaces revealed every ripple of wind is constantly changing patterns and I was mesmerised,” she says. Her work is not merely using a fisherman’s net but a scientific approach to finding the best material that makes the net-like material more strong to weather the climate yet maintain the fluidity of the same fisherman acessory.

A thin net-like mirage over the cityscape in a beautiful burst of colours is the initial perception of Janet Echelman’s sculpture but soon we realise that the mirage is much more. It is an experience that transforms with wind and light, and becomes an experience you can get lost in. What is even more fascinating is how Echelman began her craft with nets. Walking through the beaches in a fishing village in South India, watching fishermen bind the net and then hurl it to the sea, Echelman was mystified and entranced by this new material. “My first satisfying sculptures were hand-crafted in collaboration with those fishermen. I brought them to the beach and lifted them into the air to photograph them. It was then that I discovered their soft surfaces revealed every ripple of wind is constantly changing patterns and I was mesmerised,” she says. Her work is not merely using a fisherman’s net but a scientific approach to finding the best material that makes the net-like material more strong to weather the climate yet maintain the fluidity of the same fisherman acessory.

Janet Echelman’s new sculpture Earthtime 1.26 is on display in Jeddah’s new Art Promenade and seeks to heighten awareness of how all are interconnected with one another on this planet Earth.

Echelman sculpts at the scale of buildings and city blocks and her work defies categorisation, as it intersects sculpture, architecture, urban design, material science, structural and aeronautical engineering, and computer science. Using unlikely materials from atomised water particles to engineered fibre fifteen times stronger than steel, Echelman combines ancient craft with computational design software to create artworks that have become focal points for urban life on five continents, from Singapore, Sydney, Shanghai, and Santiago, to Beijing, Boston, New York, and London. Her latest creations are called Earthtime and we find out more about her art form.

This is Echleman’s first permanent and large-scale sculpture “She Changes” which measures 150 feet in diameter and was originally installed in 2005 in Portugal.

SCALE: Why are the installations called Earthtime 1.26?

Echleman: My Earthtime sculptures seek to heighten our awareness about the way we are all interconnected with one another and our physical world. They explore the contrast between the forces we can understand and control with those we cannot, and the concerns of our daily existence within the larger cycles of time. My studio modelled the physical form for Earthtime 1.26 using a scientific data set about how a single geologic occurrence in one part of the world had ripple effects all over the world. We measured the change in wave heights of the ocean’s surface as they rippled across the entire Pacific Ocean following an earthquake that originated in Chile in 2010. Its form is a manifestation of interconnectedness – when any one element in the sculpture moves, every other element is affected. The earth’s day was shortened by 1.26 microseconds as a result of this physical event so titles within the Earthtime series sometimes refer to that numerical measurement of time.

SCALE: How challenging is it to work with nets especially on the seaside with winds constantly proving to be a hindrance?

Echelman: Ephemeral materials like wind, water, and sunlight draw me in, so the patterns and direction of wind create choreography for my sculpture, whose soft surfaces undulate in ever-changing patterns. That said, in creating work to be installed in climates with the potential for extreme weather conditions including high winds, I’ve found that forms that are able to fluidly and gracefully adapt to changing circumstances are the most successful. They’re soft and flexible, able to let hurricane-strength winds pass through their soft mesh structure. Its strength is gained through resiliency, not brute force. We also use a variety of highly-engineered fibres. For example, my Ultra High Molecular Weight Polyethylene fibre is 15 times stronger than steel by weight and is the same material NASA used to tether the Mars Rover. It’s resistant to high temperatures, pollution, and even chemical reactions – all while retaining its full strength. All of our work is engineered to fully satisfy all local building code – and sometimes that means withstanding winds up to 150+mph.

“As If It Were Already Here” echoes the history of the Boston location. The three voids recall the “Tri-Mountain” which was razed in the 18th-century to create land from the harbour. The coloured banding is a nod to the six traffic lanes that once overwhelmed the neighbourhood, before the Big Dig buried them and enabled the space to be reclaimed for urban pedestrian life.

Soaring 600 feet through the air above street traffic and pedestrian park in Boston and spanned the void where an elevated highway once split downtown from its waterfront.

SCALE: When did you begin this new form of art with nets and technology? How do you keep reinventing?

Echelman: I started out as a young painter when I travelled on a Fulbright Scholarship to India. Promising to give painting exhibitions around the country on behalf of the US Embassy, I shipped my special paints and equipment to create the new paintings. The deadline for the shows arrived – but my paints did not. I was in a terrible bind, with no materials to make my art. I was staying in a South Indian fishing village, and each afternoon I walked the long beach, watching the fishermen bundling their nets into mounds on the sand. I’d seen it every day, but this time I saw it differently – a new approach to sculpture, a way to make volumetric form without heavy solid materials. My first satisfying sculptures were hand-crafted in collaboration with those fishermen. I brought them to the beach and lifted them into the air to photograph them. It was then that I discovered their soft surfaces revealed every ripple of wind in constantly changing patterns and was mesmerised.

Made from over 100 miles of twine, this 250 ft-sculpture combined hand-spliced rope and machine-knotted fibers into an interconnected mesh of more than a half-million nodes.

After returning from India, I was asked by the city of Porto, Portugal if I could build a permanent artwork for their city. I didn’t know if I could do that and preserve my art. I searched for a way to make my work durable, engineered, and permanent while retaining delicate and ephemeral qualities. It had to survive ultraviolet rays, salt air, pollution, and at the same time remain soft enough to move fluidly in the wind. We needed something to hold the net up out there in the middle of the traffic circle. So we raised a 45,000-lb. steel ring. We had to engineer it to move gracefully in an average breeze yet survive in hurricane winds. I found a brilliant aeronautical engineer who helped me create a precise shape and gentle movement. Because hand-tied knots weren’t going to withstand a hurricane, I developed a relationship with an industrial fishnet factory. Three years later, we raised the 50,000 sq. ft. lace net. It was hard to believe that what I had imagined was now built, permanent and nothing was lost in translation.

Today I work with a tight-knit group of architects inside my studio, plus an external team of aeronautical and structural engineers, computer technologists, material scientists, landscape architects, and lighting designers, as well as our fabricators who braid, loom and splice the fibre to make our sculpture. For the past 10 years, my studio has been developing a custom software tool that allows us to perform soft-body 3D modelling of our monumental designs while understanding the constraints of our craft and showing response to the forces of gravity and wind. We couldn’t have built our recent monumental city-scaled sculptures without it.

SCALE: Can you tell us about your most interesting collaborations?

Echelman: My installations are all unique to their site and so different from each other that I cannot pick a favourite. One project that was particularly meaningful to me was my temporary work in Boston (2015) along its Greenway downtown. Reshaping and drawing across airspace in the city was very exciting. The way the sculpture transformed in different weather — in the rain, in the morning light, at night with glowing illumination, the way people changed their lunchtime walks to pass by it — was really meaningful to me.

There was a grassroots website created, where people shared photos of the artwork in different weather and different times of day from different vantage points – with tips to get onto a nearby public viewing roof deck for free. It was exciting to watch it unfold. I heard many meaningful things. A woman who lived in the neighbourhood told me she felt safer now that the sculpture was there. Creating intentionality and humanising a space brings attention and safety. It poses the question of how safety can be improved by not only investing in more police officers but also investments in public art. I overheard an interview with the curator of Design Biennial Boston, which was on the Greenway at the same time. He looked up and pointed at my sculpture saying, “When I look at that, I can no longer say that anything is impossible.”

All Images Courtesy Janet Echelman.