Deafening Silence by Kader Attia

Kader Attia: On Silence, showing at Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art till the end of March 2022, is a conversation that the French-Algerian artist, who has been exploring the legacy of colonialism for 20 years, has with himself and with his viewers, taking them on a path of self-discovery. By Sindhu Nair

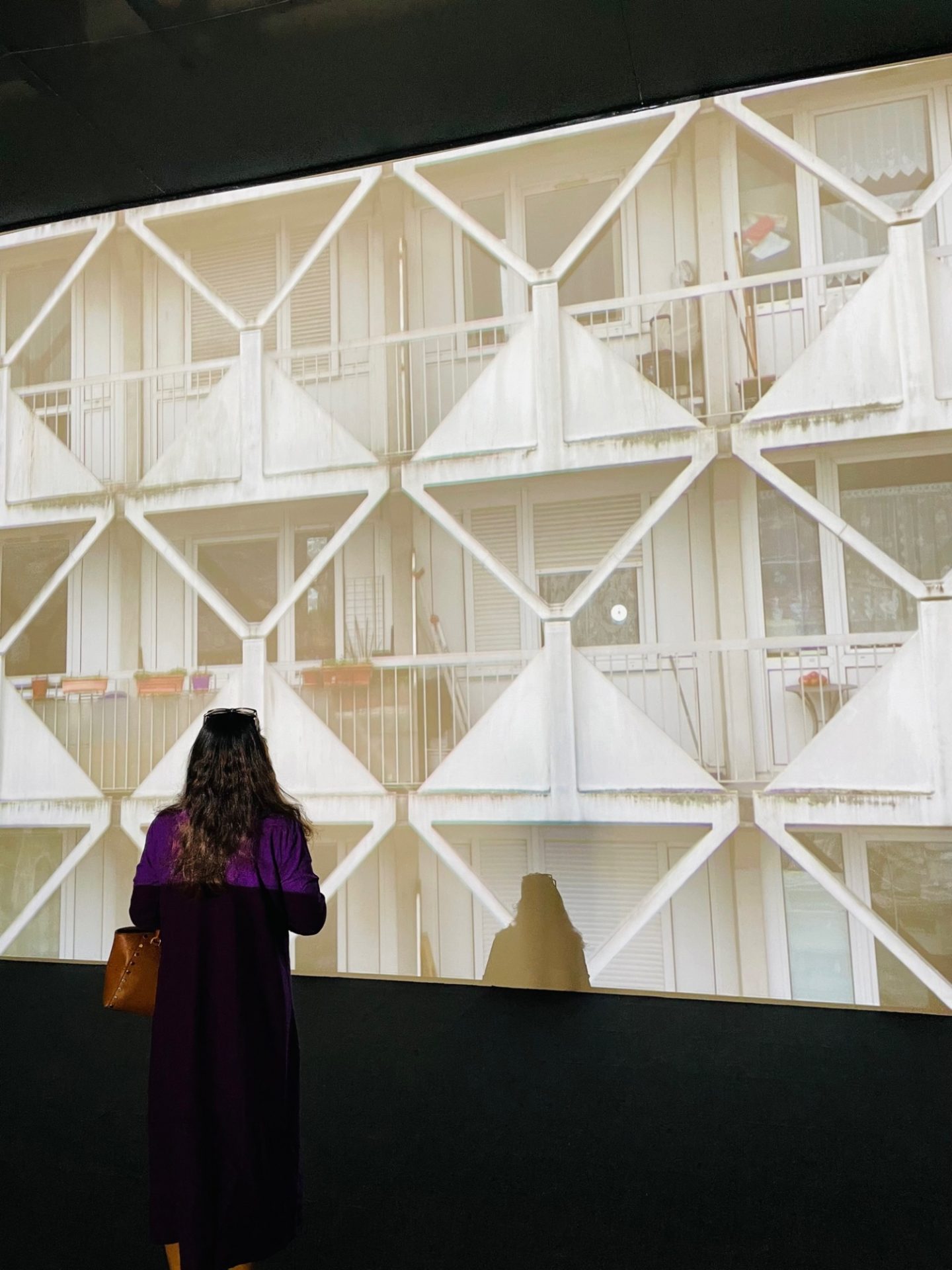

“La Tour Robespierre” (2018), that is inspired by migration and displacement from North Africa and European cities.

Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art has always had a defining effect on art lovers, the installations that usher the viewers in, the educational value of the permanent collections, and even the building with the stark white entry foyer honouring the leaders of the country in two larger-than-life paintings by Yan Pei Ming, all combine to create a well-rounded experience.

With Kader Attia: On Silence, the ongoing solo exhibition dedicated to the work of the artist over the last two decades, curated by Abdellah Karroum, the director of Mathaf, until very recently. with Assistant Curator Lina Ramadan, the audience is left spellbound, almost disbelieving what they have witnessed. Such profound works that touches on deep wounds inflicted by colonial injustices perpetrated on cultures and individuals have not been witnessed before. The curation of the work has been ingeniously accomplished, taking the viewer on a journey of self-discovery, slowly tugging at heart strings, awakening deep wounds and parallel dormant stories within themselves.

Kader Attia, artiste a lancé depuis deux ans le lieu LA COLONIE (barré) dans le 10ème arrondissement de Paris.

Attia is an artist with nearly 20 years of experience exploring the legacy of colonialism, both in France, the country of his birth, and Algeria, the land of his forefathers. Born in Paris and now based in Berlin, the featured artist Attia is the recent recipient of the Abraaj Capital Art Price in Dubai to support artists and curators.

The large foyer of Mathaf has always been awe-inspiring, but now with one of the large white hall is set up with a stage to broadcast the first work of Attia, “La Tour Robespierre” (2018), inspired by migration and displacement from North Africa and European cities, the visitor is up to speed on what to expect. The work is silent, yet thought-provoking, taking the onlooker through a drone footage of the façade of a geometrically balanced large building. This building where the artists’ and other migrants were housed, is a city’s quick response to the need of housing development, and it evokes no sense of belonging to its inhabitants, while imparting a sensation of displacement.

Ghost, 2007, aluminium foil, variable dimensions. Installation view Collector, Le Tri Postal, Lille, 2011-2012. Image courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nagel Draxler. Photo: Jean-Pierre Duplan.

But that does not prepare the viewer for the next large installation, Ghost, a collective of Muslim women in prayer, the sheer number of shrouded figures in a vulnerable position, each one different in its posture, yet bound together by the act of praying, makes one want to partake in the activity as if bound by the communion of the act. The story behind the initial production of the work is equally thought provoking, where the artist uses his mother for the casting. He says, “The casting began with my mother. She is very old and is going to die, I wanted to keep something from her. Then slowly, the more I casted other figures to complete the installation, I felt it was a Sisyphean task. I was filling the space with emptiness. The more I created, the more I felt a void, in both its physical and temporal dimensions.”

Attia renders the bodies as vacant shells, empty hoods devoid of personhood or spirit. Made from tin foil – a domestic, throw away material – Attia’s figures becomes futuristic, as it does evoke a sense of despair.

Attia renders the bodies as vacant shells, empty hoods devoid of personhood or spirit. Made from tin foil – a domestic, throw away material – Attia’s figures becomes futuristic, as it does evoke a sense of despair.

Each of Attia’s work evokes in the viewer a turmoil of mind as he or she tries to understand the artists viewpoint, his dreams or desperations as they might be, that awakens questions on post-colonial regimes, migration and cultural misappropriations.

Each of Attia’s work evokes in the viewer a turmoil of mind as he or she tries to understand the artists viewpoint, his dreams or desperations as they might be, that awakens questions on post-colonial regimes, migration and cultural misappropriations.

SCALE spoke to Abdellah Kharoum to find out more about the curatorial approach of this important exhibition. He agrees on the importance of the exhibition for Mathaf as well as for him, personally: “On Silence is a major exhibition for both Kader Attia, Mathaf Museum, and me, as we are all very much invested in the decolonial discourse. Attia is dedicating works of art that are constantly interrogating the paradox of history, and the current crises.”

“Mathaf is a museum that deals with the notion of modernity and investing in giving value and justice to artistic productions and movement from a large region that was often unfairly disregarded in cultural politics, including by the post-colonial regimes,” he says emphasizing on the importance of education in culture and the role that Museums must take on.

“I think each exhibition I curate is unique, and Kader Attia: On Silence concentrates on the combination of ideas that I think art institutions should invest in. The secret of such work resides in the hard work, the process of accompanying artist to the limit of their dreams and in challenging the institutional possibilities and making educational exhibitions,” he says.

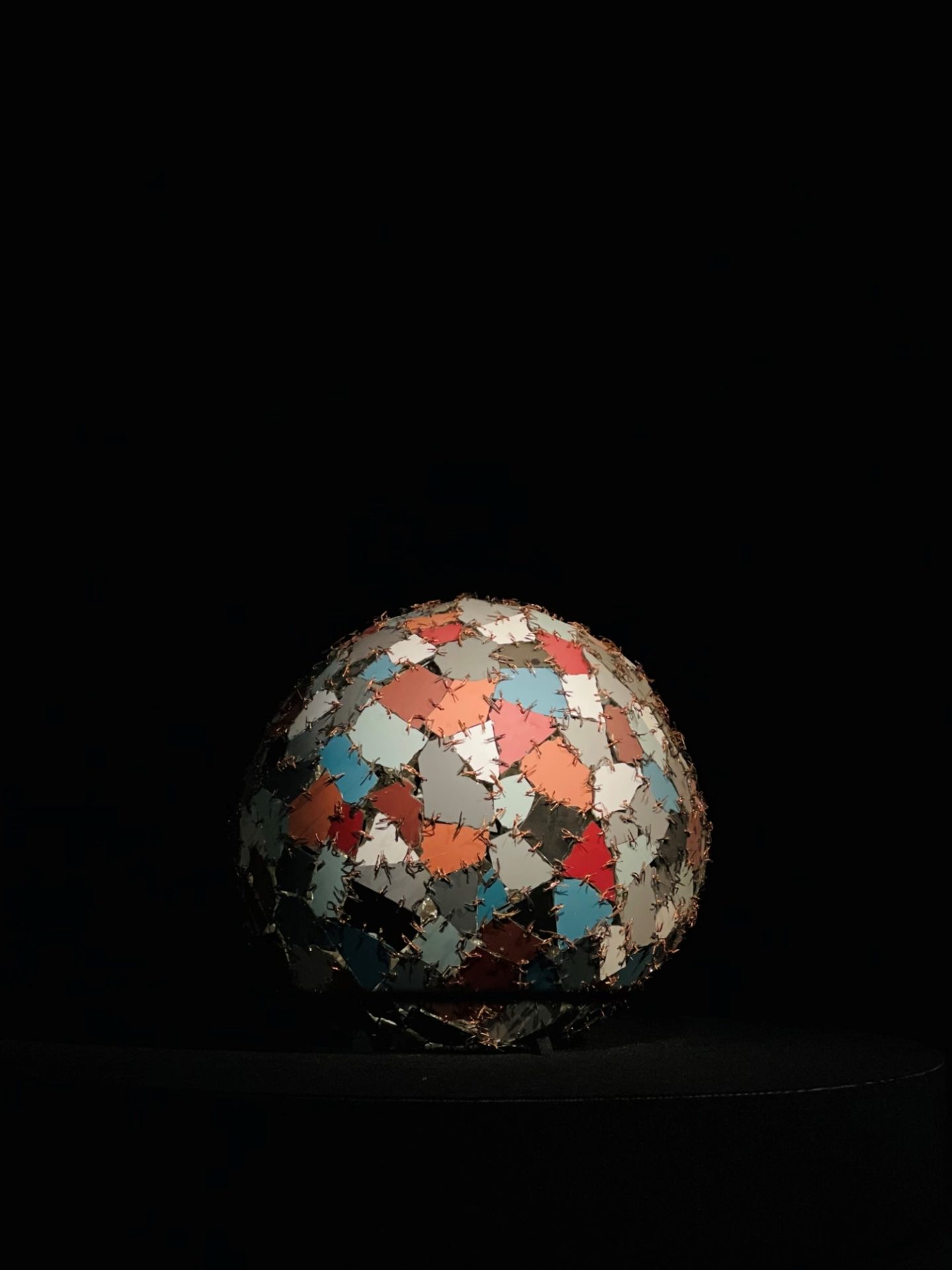

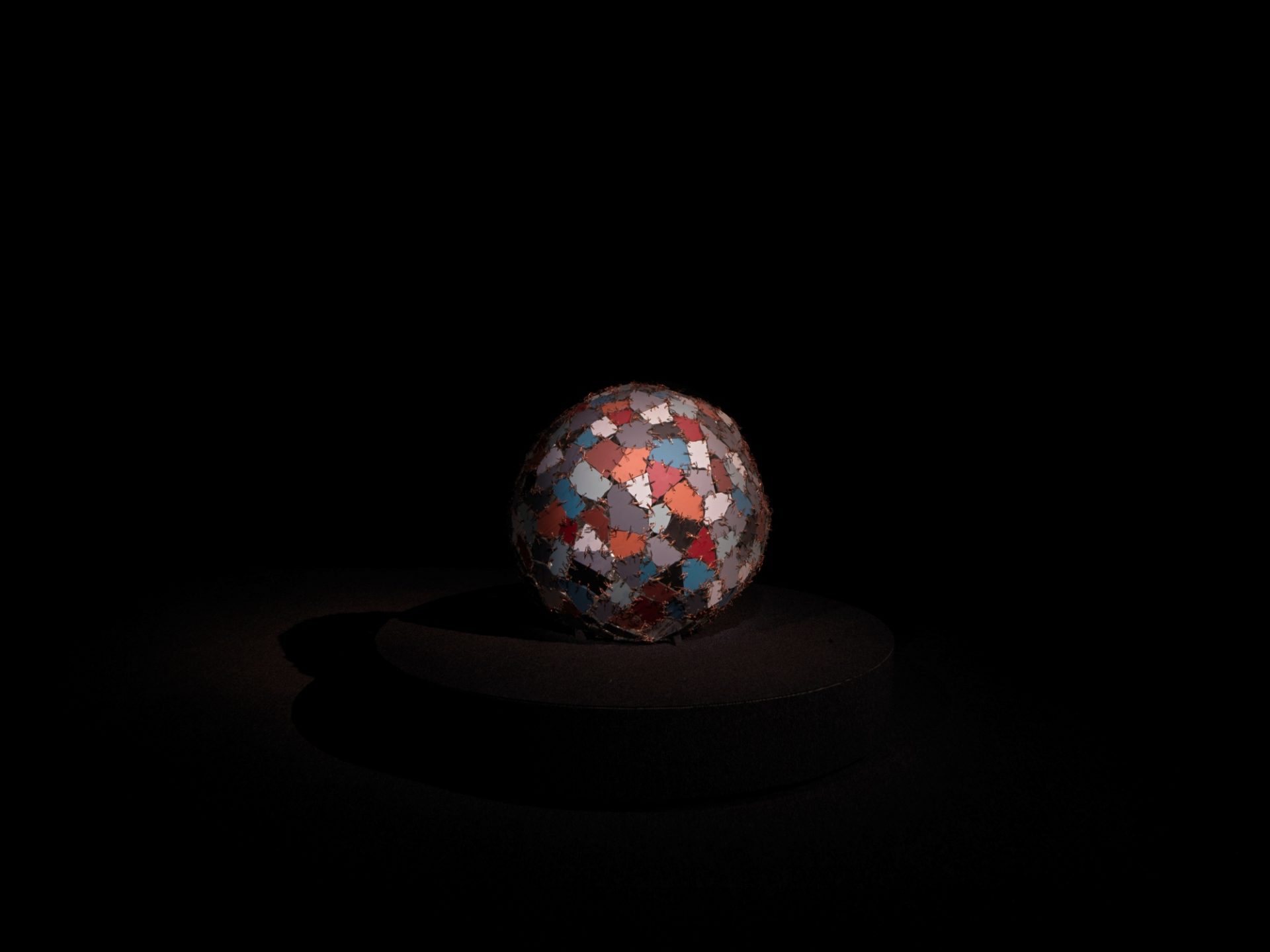

Chaos + Repair = Universe, 2014, mirror fragments, metal wires, approx. 60 cm (diameter). Installation view Sacrifice and Harmony, MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt/Main, 2016. Private Collection, Switzerland. Courtesy of Simon Studer Art and Galleria Continua. Photo: Axel Schneider.

SCALE: Kader Attia’s work is said to straddle artistic activism and educational discourse. How does he do both in the case of the Mathaf exhibition.

Abdellah Kharoum: Kader Attia belongs to a generation of artists who are actively engaged with modern social and political issues, and he is one of the most attuned within the decolonial movement. Of course, this approach is not limited to the field of art, but artists such as Attia and others that we have been working with in recent years are in continuous dialogue with philosophers, sociologists, scientists, and ecological activists. Today we can’t separate education from art production, at least not in the work of serious artists’ and museum galleries. In other words, the exhibition at Mathaf provokes the viewer by bringing visual works of art, in the form of videos, sculpture, collages and installations, and developing a clear discourse that offers time for exploration and learning. The viewers of the show can spend hours inside the Museum, or walk through the galleries and still be marked by the visual directness of the show.

Prosthesis, Comissioned by Mathaf, Doha. Physical trauma affects lves after the end of conflict – after independence is won and after slavery is abolished. Attia wants the viewers to look up and see the possiblities of trauma, the possibilities of amputated bodies.

SCALE: How important is the work of artist like Kader Attia in today’s context?

Abdellah Kharoum: Today, the world is going through multiple crises, ecological, ethical, and social. It seems that humanity is reaching a deep awareness of the destructive forces of the colonial eras, and at the same time political powers still engage their countries is similar paths, adopting problematic regimes. This paradox is addressed in many art projects, and Attia is among the most important artists dealing with these issues, both within the Museum context and in continuous connection with scholars and social activist platforms.

One of the most pressing and also challenging issues of today is the quasi-impossibility to break the silence of major problems related to human rights. The regional context is not exempt from this challenge, as many people are facing systemic racism, xenophobia and homophobia for example.

SCALE: Kader Attia often said that architecture is a tool to control individuals and the collective. Is that a bad thing? Do we not need cities and economies to be built and urban spaces formed?

Abdellah Kharoum: I think the function of architecture that you are referring to in relation to Attia’s work is both physical and symbolic. The artist talks about modern architecture that served the colonial and post-colonial project. European modern architects took inspiration from African and Asian traditional forms of architecture and developed a new vocabulary that they thought would urbanize new spaces in the colonies while they also expanded the European cities to accommodate. This formal inspiration and structure of architecture imposed a lifestyle that was double effect of colonisation. In La Tour Robespierre (2018), and in Modern Genealogy (2012-2021), the artist is talking about failure of the utopian project of Western modernist architecture to integrate immigrants. This failure is not only architectural, but it also led to a crisis of gentrification in many cities, and hundreds of towers needed to be torn down a generation or two after being built. The lesson from this story is that African and Asian architecture, that inspired European architects, was developed over centuries and responded to the people’s daily needs as well as cultural and spiritual life.

From the series Mirrors and Masks, 2013–15. Wood mask, mirror and steel, variable dimensions. Exhibition view The Museum of Emotion, Hayward Gallery, London, 2019. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Nagel Draxler. Photo: Thierry Bal

SCALE: Can you take us through the work that was made site specific for Mathaf by Kader Attia?

Abdellah Kharoum: The Exhibition at Mathaf is structed around the work On Silence (2021), occupying the entire Gallery 4 at the centre the Museum’s temporary exhibition space. This work is created for the show suspended under the high gallery ceiling, using more than a hundred protheses usually made as an attempt to repair human body after a physical trauma. The viewer is invited to look up while progressing through the exhibition space. The other major work produced for the show at Mathaf is The Object’s Interlacing (2020) dealing with the vivid topic of restitution and repair. And three other large-scale works are re-produced onsite: Ghost (2007) re-installed in Doha in collaboration with students Education City and other young volunteers; the iconic wall painting Untitled (2006) that the artist made as a site specific, Le Grand Mirroir du Monde (2017). The smaller scale works are also very important in defining the architecture and the narrative of the exhibition, all connected with the idea of fragmentation and strangely offering a view on both the form and the skeleton that structures them. My reading of this generous transparency in Attia’s approach is that he considers the viewer’s encounter and perception of the works both emotional and intellectual. This combination and inclusion of psychiatric methodologies is used at all stages of the process of making art, from field research to museum display.

Images Courtesy Qatar Museums

Photography Aadhil Naleer