The Democratisation of Complexity

Kas Oosterhuis has ticked many boxes in the field of architecture and technological innovations without losing the sculptural qualities of design while keeping within standard budgets. By Sindhu Nair

“With Saltwater Pavilion, we were able to build in 3D reality our idea of the fusion of art and architecture on a digital platform. We designed an uncompromising sculpture building, a sculpture that functions as a building, or a building that is a pure sculpture.”

Kas Oosterhuis

Director ONL | Emeritus Professor TU Delft | Researcher Qatar University |

Kas Oosterhuis is currently a researcher at Qatar University who has been designing since late 80s using parametric designs much before the term Parametricism was even coined. He could perhaps be one of the first architects in Holland to be practicing this form of design, though he says, there were others practicing it in the US.

“It was not called Parametric designs then, but we already did it. It later became fashionable to call this Parametricism. It was called Associative Design, back then, because it was basically about relationships between components.”

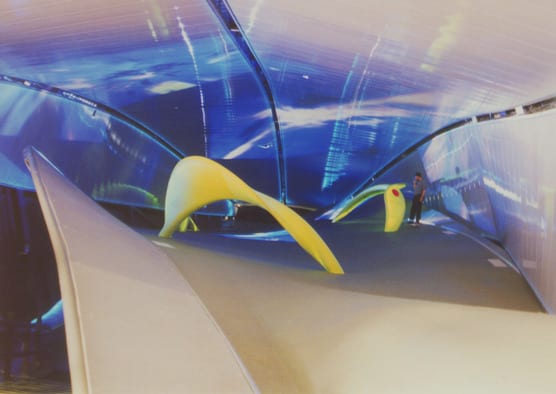

Kas is also the Director of The Innovation Studio, ONL, a multidisciplinary office, which he runs together with his partner in life and business, visual artist Ilona Lénár. The projects he has designed vary from small housing projects to large-scale cultural buildings, acoustic barriers, and commercial buildings. The firm started with the intention of merging art and architecture on a digital platform and that has been the brief for each of Kas’ designs, buildings that are as sculptural as an art form. In the process of bringing to life sculptural forms as functional buildings, he discovered a new process of design to production where the data produced in 3d models were directly communicated with the cutting machines for the manufacturing of the steel components of the structure, making the entire process seamless. That was not the last of the innovations masterminded by Kas, each of his projects was an answer to making sculptural forms easier to design, build and program, the next one better than the one before.

“The intentional byproducts of our systemic parametric design to robotic production approach were to bring art and architecture on the same level playing field, to create a new nonstandard form of natural complex variability, and to have this done within standard budgets, a form of democratization of complexity,” he says.

Kas feels strongly about the lack of a strong art community in Doha: “I believe that the future of architecture is not so much in the design of more office buildings and repetitive residential apartment towers, but in culture-driven structures that are to be enjoyed by the public while drawing attention to an international crowd of visitors.”

The A2 Cockpit is a 6.000 sq meter showroom and garage for luxury cars, embedded in a 1.6 km long acoustic barrier, as a landmark for the upmarket industrial area behind the barrier. ONL [Oosterhuis_Lénárd] developed an efficient algorithm to describe all the 40.000 different components of the Acoustic Barrier and the Cockpit and communicated the production data for their unique dimensions and angles directly to the machines of the steel manufacturer.

The A2 Cockpit was built for a truly competitive price of 800 EUR/m2 all included. By virtue of the sweeping long elastic lines, the interior of the A2 Cockpit feels like a long stretched terminal building [169 m’] rather than the usual boxy showrooms.

“I had a student in Qatar University, who proposed a whole area in Doha suburbs as an art district, an informal enclosure with numerous studios that brings together the artist community,” he observes as he spends lockdown time in Hungary, where his artist wife, Ilona Lénárd is from, missing the vibes of a country that is on the path of self-awareness and a society that is growing in its artistic consciousness.

Being a mentor and in a unique position to look at what is happening in Doha, both from within and from outside, he seems to have a pragmatic view of how the country is being shaped.

The 25.000 sq metre Bálna Budapest [2013] is a cultural center located on a prime location facing the Danube river. Kas designed it as “go with the flow”, applying a dynamic that matches the direction of the flow and jutting out forward to indicate the new urban development towards the South of Budapest.

The team at ONL applied the structure plus skin system that was developed for the A2 Cockpit. All in one generous gesture, the Bálna transforms gradually from the cantilevered entrance canopy at the City end vai a large atrium roof into the main building body and finally to the forward-looking overhang at the Southern end.

“I feel very proud to see how the country has gone through self-realization during the GCC blockade, teaching itself to be self-reliant and to have come out of this crisis much stronger than earlier,” he says.

He also talks about one strength of the country that he has not seen anywhere before, “The strength and the willpower of the women in Qatar, to rise above challenges, not to take a lesser role but to drive and to lead innovations to be it in the field of art, architecture, science or technology, is exceptional,” he says, “This is greatly stimulated by HH Sheikha Mozah bint Nasser and that helps a lot.”

Kas takes the example of one of his students who is one of the first lady architects in Qatar, Badria Kafood who started her own practice, and though she does face difficulties in doing business, continues steadfastly.

SCALE conducts a Zoom interview with Kas to learn more about the historic work that seems to have missed being written about, in the pages of parametric design evolution.

The De Kassen social housing project in Amersfoort featuring a merge of graphic art and architecture on the grand scale of architecture.

What happened before the Saltwater project and how did this work define your practice?

In 1986-1987, I designed and executed the head office for BRN Catering near Rotterdam, the first work under my own name as the lead architect. Before that, I was a freelance designer working with a prolific Dutch architect Peter Gerssen, and we designed together for example the Zwolsche Algemeene HQ near Utrecht. After BRN Catering, I went together with my partner in life and business Ilona Lénárd to live for one full year in Paris to reflect upon my position in the profession. We decided there that we wanted to merge art and architecture on a digital platform and in 1989 we founded our innovation studio ONL. Our first joint projects were the patio housing in The Hague [1990] and the De Kassen social housing project in Amersfoort, both featuring a merge of graphic art and architecture on the grand scale of architecture. Our joint goal was to develop buildings as big art projects and vice versa large art projects as habitable constructs. We organized in 1994 a big event titled Sculpture City, with an exhibition, an international 3D printing workshop, a global internet workshop, and a book with CD ROM, which was the first publication of its kind at that time in The Netherlands.

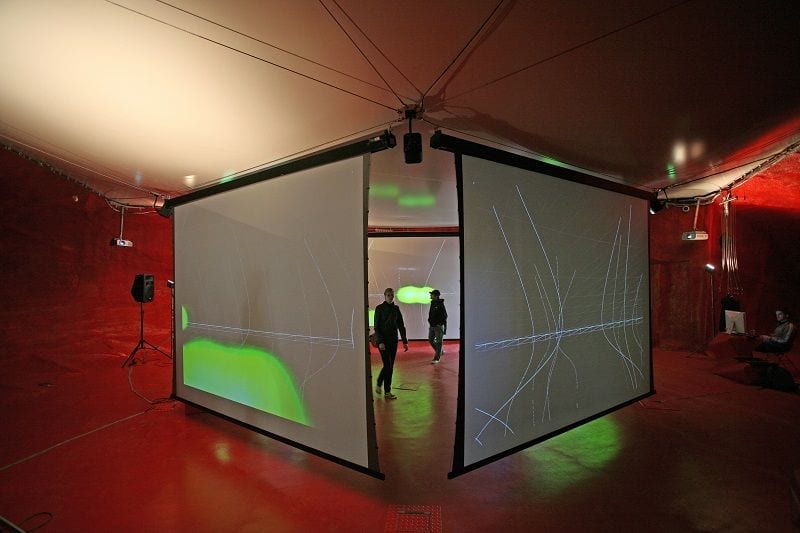

The Saltwater Pavilion was an absolute first in creating an interactive interior environment integrated with the building design

The building body would no longer be a static body, but could be considered as a programmable entity, displaying behavior while interacting with its immediate environment, says Kas about the design of Saltwater Pavilion.

SCALE: You have described the Saltwater Pavilion as a sculpture building, both sculpture, and building, and the first-ever to use scripting techniques to connect the fluid design to the procedural production methods. Tell us more about the process and architectural innovation?

KAS OOSTERHUIS: Our ideas drew the attention of the well-known Indian-Dutch urban designer Ashok Bhalotra who invited us to design the Saltwater part of the Water Pavilion, in a combined effort with NOX architects who were responsible for the Freshwater part. The Saltwater Pavilion became famous for innovations on many levels. First, we were able to build in 3D reality our idea of the fusion of art and architecture on a digital platform, we made what we had so strongly advocated a few years before. We designed an uncompromising sculpture building, a sculpture that functions as a building, or a building that is a pure sculpture. Second, we developed a completely new and extremely efficient way of communicating with the steel manufacturer. We developed a new process of design to production and coined it the File to Factory process, meaning that the data that we produced in our 3d models were directly communicated with the cutting machines of the steel manufacturer. The steel manufacturer Meijers Staalbouw conveyed to us that we were the first to take advantage of the potential of the machines that he already had in his workshop for 15 years! Which is telling how slow architects typically are in adapting to new technologies. Without our File to Factory process, the building would have been much more expensive to build, now we managed to deliver our smooth curvilinear sculpture building within the given standard budget. Third, the Saltwater Pavilion was an absolute first in creating an interactive interior environment integrated with the building design. We harvested raw data from a buoy on the North Sea and translated these data into MIDI signals to control the light and sound environment in real-time. The public could interact with the program in real-time by pressing the sensor boards that we embedded in the Hydra structure that we had embedded as a structural component in the undulating twisted floor. The statement we made was that a building body would no longer be a static body, but could be considered as a programmable entity, displaying behavior while interacting with its immediate environment.

SCALE: You have consistently made history by using parametric designs when it was a completely new form of technology to be used in architecture. Take us through the buildings that were totality parametrically designed and CNC produced?

KAS OOSTERHUIS: In 2001-2002, we took another radical step. We developed the concept of “One Building One Detail” for the Web of North-Holland on the Agricultural World Expo at the Floriade in the Haarlemmermeerpolder [near Schiphol Airport]. Or, as I like to provoke in lectures: “Mies Is Too Much”. We wanted a full structure-skin synchronization, whereas both the structural components, the skin components, and their mutual connections would form part of one ruling parametric detail. After having defined the point cloud of reference points of the surface of the Web of North-Holland, we mapped this all-encompassing parametric detail on the overall surface, covering both the convex and the concave areas. Even the upward hinging doors, which were in fact a cutting out of the structure-skin system, we’re following the same parametric detail. We took nothing from a catalog, we designed our own project-specific catalog of parts, whereas every component, the thermal heat cut steel plates, the laser cut aluminum skin plates, the customized steel connectors for the steel parts, the aluminum connectors for connecting the skin with the structure, formed part of that one single parametric detail. The fascination was – and still is – that by introducing such a strict regime of limiting the number of different details a new form of complexity naturally emerges. The year after the world expo the pavilion was taken apart in its components and rebuilt for its second life as the iWEB laboratory for my Hyperbody research group at the TU Delft. Tragically, the iWEB was demolished while the faculty building had been burnt down in 2007 and the Faculty of Architecture was moved to another location.

SCALE: What are the advantages of using a parametric design while designing a building? Is it leaving too much to technology or does it give the architect the to design imaginatively without constraints of its structural feasibility?

KAS OOSTERHUIS: The intentional byproducts of our systemic parametric design to robotic production approach were to bring art and architecture on the same level playing field, to create a new nonstandard form of natural complex variability, and to have this done within standard budgets, a form of democratization of complexity. Exactly by creating a strict framework for the interacting components that constitute the building, we were able to free the imagination. Basically, by stretching the extremes, in one direction to a set of simple rules, and in the opposite direction into the realm of complex geometry, we managed to substantially expand the working space of the designer. We have proven that limiting the number of different details does not lead to a boring product. In contrast, it opens the road towards natural diversity. As in nature all leaves of a tree are different, as all birds in a swarm of birds are different and having their own identity, we developed a systemic approach that effortlessly invokes such natural beauty, It is not only the geometry that is orchestrated in the single parametric detail, the systemic approach also includes structural calculations, determining the thickness of the constituting parts, calculating the number and distance between the bolts that are needed to keep the structure standing. Potentially, but not yet applied, is the climactic performance of the systems as well, seen in relation to the whole of the building. In the [very near] future we will calculate the exact necessary amount of insulation needed for that specific component in that specific location in the building. We can do that while the system is based on addressing each individual component separately in the scripting procedure. The motto we are faithful to here is “Where, when, and as needed”. Contrary to the common belief, such struct systemic approaches featuring the real-time calculations are substantially enhancing the creative power of designers, it literally unchains them from building standards and conventions.

The 20,000 sq metre Liwa tower got its name from the owner,. He said the shape and the coloUrs reminded him of his birthplace, the Liwa Oasis, at the edge of the Empty Quarter with its majestic reddish sand dunes. The Liwa tower is the first truly parametrically designed building from top to bottom in the Middle East. Structure and skin are fully integrated and locally produced according to ONL File to Factory guidelines. ensuring a competitive price for such commercial office towers.

We managed to successfully apply the bespoke and cost-effective parametric design to the robotic production method to much larger structures such as the A2 Cockpit in The Netherlands, the Bálna Budapest cultural Centre, and the Liwa tower in Abu Dhabi.

SCALE: What are the other innovations that you have pioneered, and do you think that AI is the way to go in the future of designing?

KAS OOSTERHUIS: Currently, we are working on a participatory urban design instrument called the Participator. Participator is meant to create a level playing field for different disciplines designing together from scratch. And not experts in their field but also laymen, users, and members of non-governmental organizations can play this serious game with the group. Each player is authorized to play with the rules and the rules, in full transparency for all to see what the effect of proposing changes in the values of the parameters is. In Participator, we can set explicit goals and performance criteria while leaving the road to achieve that fully open. As they say, there are several roads leading to Rome, and this is exactly the paradigm we want to work in. There is no such thing as the perfect solution for a problem, there are always many ways to reach your goals. The participator is meant to create design characters whereby each player respects the other without trying to dominate. It is a known acknowledged problem that the traditional linear building chain architect > engineer > specifications > tender procedure > contractors > subcontractors offer no feedback possibilities between these players. Participator is developed to offer a platform where all players can act together from scratch. We have tested Participatory across various situations with project developers and the feedback is very positive. Currently, we are developing this participatory design instrument further and will bring it to the market.

SCALE: Tell us about your work in Doha?

KAS OOSTERHUIS: We have done a concept design for a retractable roof for the Al Hazm Mall to filter the strong sunlight and to reduce the ground temperature in the open spaces between the buildings, which is under consideration by the CEO whether to implement. We participated in a competition for West Bay North Beach, but apparently, we did not win the competition, neither was there a winner announced. I noticed recently that Ashghal has developed a plan themselves to develop this area by transforming it into a public beach with facilities, replacing the now abandoned former Embassies along Diplomatic Street.

We organized a robotic workshop with students at Qatar University in Doha Fire Station titled “Machining Emotion”, and exhibitions of Ilona’s paintings were exhibited at the Sheikh Faisal Bin Qassim Museum and in Doha Fire Station. I delivered many lectures; we were asked to mentor the artists in residence at Doha Fire Station and installed a quite big interactive inflatable sculpture titled “Little Babylon”.

Little Babylon is an interactive inflatable sculpture titled that interacted with the tweets of the public. The words of the tweet were harvested, categorized, and processed as information to define the “mood” of the sculpture, in real-time changing its colours and sound fragments

Currently, Ilona and I are working with a team of bright young Qatar-based female designers from Jordan, Syria, and Egypt on a design of a huge public sculpture titled the 7 Daughters, a large event structure that will be accessible for the public, and truly a sculpture building. We cannot disclose the design at this moment, but the plans will be out soon.

At Qatar University I am currently involved as an expert consultant in two major research projects, the NPRP funded Qatar Robotic Printing research, focusing on using local materials, led by Dr. John Cabibihan of the College of Engineering, and the M-NEX Belmont research project, led by Prof Sami Sayadi of the Center for Sustainable Development, by and large dealing with the Food-Energy-Water Nexus, eventually leading to a proposal for a master plan for Qatar University as a Living Lab.

SCALE: Your insights into the architecture at West Bay and the cultural stamp of the country. Has it left a positive impact on you as a designer? What more would you want your city, Doha to be?

KAS OOSTERHUIS: We enjoyed living in the Falcon Tower in West Bay. We found it a very good location close to walking distance to the Hotel Park and the Corniche. We often went out, even in summer to have a stroll along the bay. I strongly believe in high-density city centers, in combination with very low-density residential areas. Yet, there are many improvements we could think of. First, I believe one should take a good look at the unfinished towers and find possible different usage for them. I have proposed in a tender procedure where we participated in the Corniche Tower to transform the building to make it Food-Energy-Water Nexus compliant. This would imply to extend the wings with an Urban Farming topping providing for food for at least the whole complex, a Solar Tower providing for its own electricity on top of the central core, and a Water Harvesting structure on top of the second wing. Thus, it would become a fully self-sufficient networked building, negotiating levels of production with immediate neighbors, providing for local demand of food, energy, and water, as an example of how to rethink the ecosystem of cities.

Furthermore, anticipating the ubiquitous use of automated electric vehicles soon, we must really rethink the mobility infrastructure.

Basically, it will come down to a complete make-over of the 8-12 lane city streets, to transform them into walkable generously shaded areas with an abundance of large trees, where pedestrians can easily mix with bicycles and slower-moving automatic vehicles. This would transform West Bay into a thriving livable open city, with not too much effort. On the other side of the habitat spectrum, private homes would need to become self-sufficient as well, stimulating home growth of food, applying solar energy, and introducing individual local water harvesting. It can be done, without too many additional costs, in a 5-10-year payback time. Thus, the low-density residential areas could become a wealth of private lush green domains.

SCALE: How has lockdown and the Coronavirus impacted the design community? What have we done wrong till now that has to be changed to combat such pandemics?

KAS OOSTERHUIS: In retrospect, we have done almost everything wrong according to today’s standards. But we cannot blame previous planners and designers for what they have chosen to do, because they were living up to the standards of their time. Now in the post-covid era, times are changing, and changing faster than ever. In building technology, we will see a nonstandard parametric design to robotic production become the new standard, while it substantially reduces waste, avoids overproduction of standard components, reduces CO2 exhaust, improves the working conditions of the laborers, is painfully exact in the assembly of parts, needs substantially less labor force, addresses each citizen personally while offering a platform for user participation. Thus, bringing the building industry on a higher scientific level of development.

In city planning we will see a massive forestation to provide the citizens with pleasant shade and natural cooling, streets will be drastically narrowed to 2 lane roads to suit the reduced space consumption of automated electric vehicles, resulting in a substantial drop in car accidents, collateral deaths and clear air in the city.

Arts and culture at large, and more in general the quality of life for all citizens, will become an even more prominent economical factor, thereby reversing global climate change by replacing gas and oil as the main economic driver, Definitely, many signs are pointing in this direction.

1 What you miss most when in Doha

A cultural awakening, artist evolution and loads of greenery.

Doha should plant millions of trees and reduce the size of the streets and give way to pedestrians and cycle paths and e-bikes.

2 One aspect of Doha that you will always want to carry with you.

The female-power in Doha is something phenomenal that I have not seen anywhere in the world and since I work at the Qatar University. It is not feminism, but it is a feeling of leading change.

3 An architect who has inspired you.

Oscar Niemeyer in the 80s, also architects like Super Studio, which was quite a radical movement in Italy, a combination of very essential architecture while being critical. Today. Jean Nouvel does a lot of great work.

Later, it was Robert Aige, a programmer, who used to work with Arup and then later for Bentley Systems.

4 One activity that you were constantly engaged in while in lockdown that kept you in a positive mode:

Writing a book.

5 A city you want to visit after the pandemic

Doha, of course.

All images Courtesy ONL

Cover Image Courtesy Jan de Bruin