Masjid an-Noorayn: An Invitation to The Spirituality in You

Masjid an-Noorayn designed by Common Ground is understated elegance in raw concrete that quietly envelopes the visitor in tranquillity and self-reflection. By Sajini Sahadevan

How can one evoke spirituality without relying on the typical symbols associated with it?

How can one evoke spirituality without relying on the typical symbols associated with it?

This is the thought that drove architect Simi Sreedharan, founder, Common Ground, alongwith her team at the firm, when designing Masjid an-Noorayn (Mosque of Two Lights) at Panambra in Malappuram district of north Kerala, India.

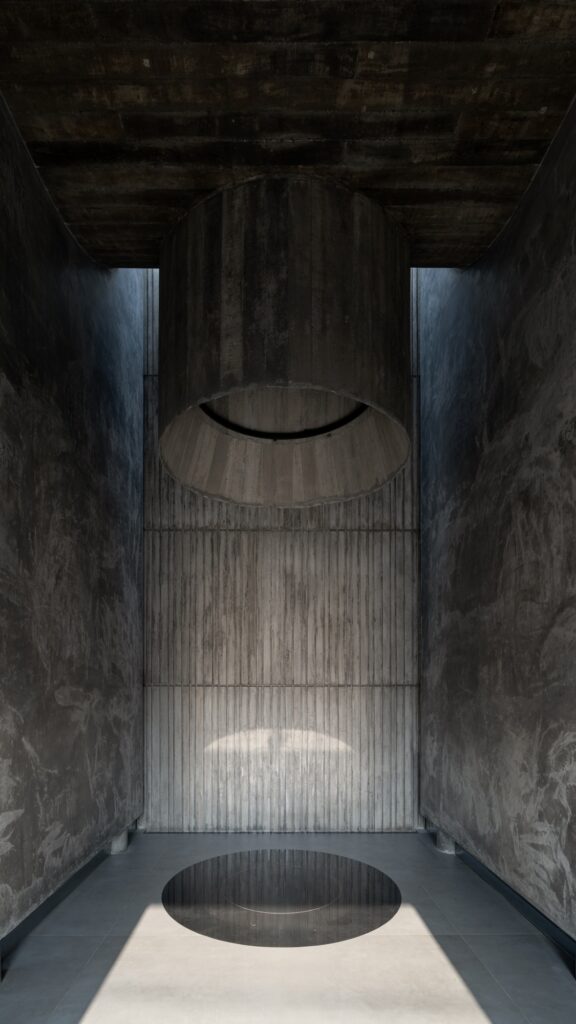

Simi’s team likes to call it the ‘Mosque of Light and Shadows’ taking into account the interplay of both elements in the design that create the mystical ambience throughout the day. Where most mosques evoke a sense of awe with grandeur achieved through scale and ornate details, Masjid an-Noorayn is, on the contrary, a bold yet stark understatement. Finished entirely in raw concrete, it leads one to arrive at an individual invocation of spirituality, as the colour grey takes on a new dimension within the walls of this mosque.

“Darkness and light co-exist. Imagine a space flooded with strong light. It will not help us understand a space. Now imagine a dark room into which minimal light is released. It makes that light precious and divine. Contained shadow provides a space for psychological refuge. Letting in controlled light from the top acts like a channel for that spiritual dimension,” Simi explains.

“Darkness and light co-exist. Imagine a space flooded with strong light. It will not help us understand a space. Now imagine a dark room into which minimal light is released. It makes that light precious and divine. Contained shadow provides a space for psychological refuge. Letting in controlled light from the top acts like a channel for that spiritual dimension,” Simi explains.

A winner of coveted state recognitions such as the IIA Gold Leaf award (2021) and Silver Lead award (2013 and 2023), Simi’s team had the confidence of the client, a longtime associate, to experiment with the concept.

Light is the most important element at Masjid an-Noorayn. Completed earlier this year in 2025, all the elements one identifies with for a mosque has been done away with, be it on the exterior or interior, of the 1900 sq.ft. structure.

Light is the most important element at Masjid an-Noorayn. Completed earlier this year in 2025, all the elements one identifies with for a mosque has been done away with, be it on the exterior or interior, of the 1900 sq.ft. structure.

The original mosque was smaller in size, built by the client in Malappuram for his family and those in the neighbourhood. Road acquisition by the government as part of developing the highway in the area led to it being demolished. The client left it to Common Ground to use a part of the plot where they resided on the service road to construct a new mosque instead.

The original mosque was smaller in size, built by the client in Malappuram for his family and those in the neighbourhood. Road acquisition by the government as part of developing the highway in the area led to it being demolished. The client left it to Common Ground to use a part of the plot where they resided on the service road to construct a new mosque instead.

Spirituality in Architecture

For Simi, it was a thought she had been nurturing for a while – a mosque as a project to explore spirituality in architecture.

For Simi, it was a thought she had been nurturing for a while – a mosque as a project to explore spirituality in architecture.

“Other places of faith, such as temples, make one feel spiritual because of the layered planning that forces one to pass through many layers of transitional spaces, each time readying the person, till the sanctum sanctorum; churches too, by way of scale and proportion, create that feeling of magnificence required for communal prayer. The earliest mosque structures did not have any symbolic elements that we generally associate with mosques these days. We had beautiful contextual mosques in the beginning in Kerala, as with everywhere else in the world. But over the years, our perception started to change, associating mosques with certain elements or colour. In many instances, mosques are just buildings with no soul at all. The Quran says nothing about a space for prayer — it can be anywhere. So then where did these influences come from? We wanted to know if a mosque could be designed this way as it seemed to have so much potential.”

Masjid an-Noorayn does not have any of the typical symbolic elements associated with a mosque – be it domes or arches. The one archetypical feature – a minaret, was included to serve as a visual element as the mosque is located on a service road and is not visible from the highway. Simi’s research showed her that none of these elements were a necessity.

Masjid an-Noorayn does not have any of the typical symbolic elements associated with a mosque – be it domes or arches. The one archetypical feature – a minaret, was included to serve as a visual element as the mosque is located on a service road and is not visible from the highway. Simi’s research showed her that none of these elements were a necessity.

“These are things that came over time. So we wanted to experiment, to know if it was possible to create such an environment without the arch or the dome.” The team’s case studies included the four-storeyed Kuttichira mosque built in 650 AD. As for exceptionally-designed contemporary mosques, Simi found much resonance with Marina Tabassum’s 2016 Aga Khan award-winning Bait Ur Rouf Jame in Dhaka designed with terracotta brick as the material and natural skylights.

A massive revolving door marks the entrance of Masjid an-Noorayn. The back of the mosque which faces the qibla is a focal freestanding wall. It is detached from the rest of the structure but runs across the length of the whole building.

A massive revolving door marks the entrance of Masjid an-Noorayn. The back of the mosque which faces the qibla is a focal freestanding wall. It is detached from the rest of the structure but runs across the length of the whole building.

The rest of the structure sits floating on pillars with a glass element below from where subtle light spreads into the space, creating an ethereal atmosphere. With the palette minimal and the material being just one — concrete, fully exposed, the flooring too is of the same colour.

Spaces to Pause and Interact

Taking into account the mental state of a person who comes to pray was key apart from seeing that the mosque also functioned as a place of rest for passers-by who needed a stopover to freshen up. Apart from the prayer hall which remains closed except during namaz the other areas are open to the public at all times.

Taking into account the mental state of a person who comes to pray was key apart from seeing that the mosque also functioned as a place of rest for passers-by who needed a stopover to freshen up. Apart from the prayer hall which remains closed except during namaz the other areas are open to the public at all times.

“When people come to pray, there’s so much on their minds from the day. It is a state of rush. So, we introduced a foyer space to create that pause before entering the prayer halls. This is the only element that has changed from the first sketch we did, otherwise everything else is the same,” Simi elaborates.

People tend to spend some time catching up as they live in the area so an extra space was created for community interaction. On the other side of the back wall is the client’s house from where they too can enter the Masjid an-Noorayn.

The structure is bereft of windows, breaking the norm once again to forego an element that is otherwise seen as necessary to bring in light. The prayer hall of Masjid an-Noorayn has an inverted arch, a linear skylight from the top, through which light falls on the side walls as it does through the minaret.

Men and women pray facing the same wall which reflects light and so also creates shadows all day. There are no distractions, deliberately so, at eye level. “One can actually tell the time of day just by sitting there. It is a meditative experience,” Simi says, pleased to have achieved the brief they started out with.

Men and women pray facing the same wall which reflects light and so also creates shadows all day. There are no distractions, deliberately so, at eye level. “One can actually tell the time of day just by sitting there. It is a meditative experience,” Simi says, pleased to have achieved the brief they started out with.

Unlike in most mosques where the minbar is located off-centre, it took Simi’s team considerable brainstorming before deciding to place it in the middle of the room. This, again, is not without reason. Symmetry, she notes, plays a large part in spiritual architecture. It was resolved by introducing a two-step podium with a sliding stand which remains out of sight when not in use. The central minbar under the skylight also remains the only space painted white amidst the sea of grey.

Unlike in most mosques where the minbar is located off-centre, it took Simi’s team considerable brainstorming before deciding to place it in the middle of the room. This, again, is not without reason. Symmetry, she notes, plays a large part in spiritual architecture. It was resolved by introducing a two-step podium with a sliding stand which remains out of sight when not in use. The central minbar under the skylight also remains the only space painted white amidst the sea of grey.

A Mosque for All

Simi’s team comprises women Muslim architects well aware of the need for a dignified space as a prayer hall for women, and not as an afterthought.

Simi’s team comprises women Muslim architects well aware of the need for a dignified space as a prayer hall for women, and not as an afterthought.

“The women’s prayer hall is usually a last-minute decision or relegated to a space after the toilets or ablutions area. So we proposed a self-sufficient prayer hall with an entrance from the front for women right in the design concept itself.”

The women’s prayer hall and foyer have shelves for abayas and hooks to hang their clothes or bags.

The women’s prayer hall and foyer have shelves for abayas and hooks to hang their clothes or bags.

The foyer to the women’s prayer hall is also home to two nutmeg trees. “When we first did the set-out, there were two trees on both sides of the ladies’ entrance. We retained them and added the nutmeg trees inside. We chose the trees to signify the spice trail and the relevance of Islam in its history,” Simi says.

The foyer to the women’s prayer hall is also home to two nutmeg trees. “When we first did the set-out, there were two trees on both sides of the ladies’ entrance. We retained them and added the nutmeg trees inside. We chose the trees to signify the spice trail and the relevance of Islam in its history,” Simi says.

The mosque is fully airconditioned, considering climatic conditions and the fact that quite a bit of body heat is generated when 100-150 people congregate in close quarters in an indoor space. All fittings are state-of-the-art, from the two large digital screens that display the timings for prayer and related information from an app to the speakers. Niches in the walls hold copies of the Quran while storage spaces stay concealed where foldable chairs are kept.

The mosque is fully airconditioned, considering climatic conditions and the fact that quite a bit of body heat is generated when 100-150 people congregate in close quarters in an indoor space. All fittings are state-of-the-art, from the two large digital screens that display the timings for prayer and related information from an app to the speakers. Niches in the walls hold copies of the Quran while storage spaces stay concealed where foldable chairs are kept.

The space was warmly received with women expressing their gratitude to the team for breaking the norm where normally such places are “dark and intimidating”. It is now regularly used by young women who look forward to offering prayers at the Masjid an Noorayn.

The space was warmly received with women expressing their gratitude to the team for breaking the norm where normally such places are “dark and intimidating”. It is now regularly used by young women who look forward to offering prayers at the Masjid an Noorayn.

The first time Masjid an-Nooryan were opened for prayers saw packed halls. Feedback has largely been positive though there is the occasional expression of disapproval. Reels of the mosque have raised a lot of curiosity.

The first time Masjid an-Nooryan were opened for prayers saw packed halls. Feedback has largely been positive though there is the occasional expression of disapproval. Reels of the mosque have raised a lot of curiosity.

Simi laughs saying one of the most common comments they receive is, “Who let you do this?”. She credits the client with the results achieved. “Till the end, I doubt if our client knew what to expect.”