Reconnecting the City with its Rivers

Co.Creation Architects win the Aga Khan Award for Architecture 2022 for putting the focus back on rivers. What is most commendable about the project was the enthusiasm of the community, resulting in Jhenaidah Municipality employing local craftspeople to execute the project with the architects providing pro-bono consultancy services. The final result was the conversion of a derelict informal dump site alongside the bank of the river into an attractive and accessible multifunctional space valued by Jhenaidah’s diverse communities.

Recent urban expansion in Bangladesh has seen its originally river-facing cities become road and land-focused, their watercourses reduced to backyards and dumping grounds. One such is Jhenaidah, where architects Khondaker Hasibul Kabir and Suhailey Farzana grew up. Keen to enhance the quality of life here, they moved back from Dhaka in 2015 and instigated a participatory initiative to enable low-income communities to build their own houses, followed by an extensive series of “Co-Creation Workshops” engaging citizens to rethink the city’s public spaces.

The area was difficult to access in spite of its central location. The municipality accepted to break paths in several walls in order to make the ghat and the river easily reachable.

Putting the resulting visualisations into action has produced the Urban River Spaces, which so far comprise two ghats (steps leading to waterside platforms) plus adjacent walkways and access pathways – reconnecting the city to the river. All visible surfaces were in local brick.

The ghat was built with brick and concrete by local masons. It was designed with respect for the local topography.

By far the larger of the ghats, the 115-metre-long “public ghat” has two plateaus linked by various stairways and a ramp for the disabled, with the lower plateau remaining at least 3.7 metres above the water. People of all ages and backgrounds, including some from nearby towns and villages, regularly come here to walk, sit, meet, or engage in sport, cultural or recreational activities. The upper retaining wall serves on the lower plateau as a vertical surface for public exhibitions, and on the upper one joins with a parapet that meanders around the pre-existing trees – some over a century old – to create semi-enclosed, shaded areas where people can sit facing each other. This ghat can also serve as a two-level auditorium for theatrical performances given on a floating deck or on the opposite riverbank.

The site of the public ghat has the benefit of large pre-existing trees that provide shade throughout the day.

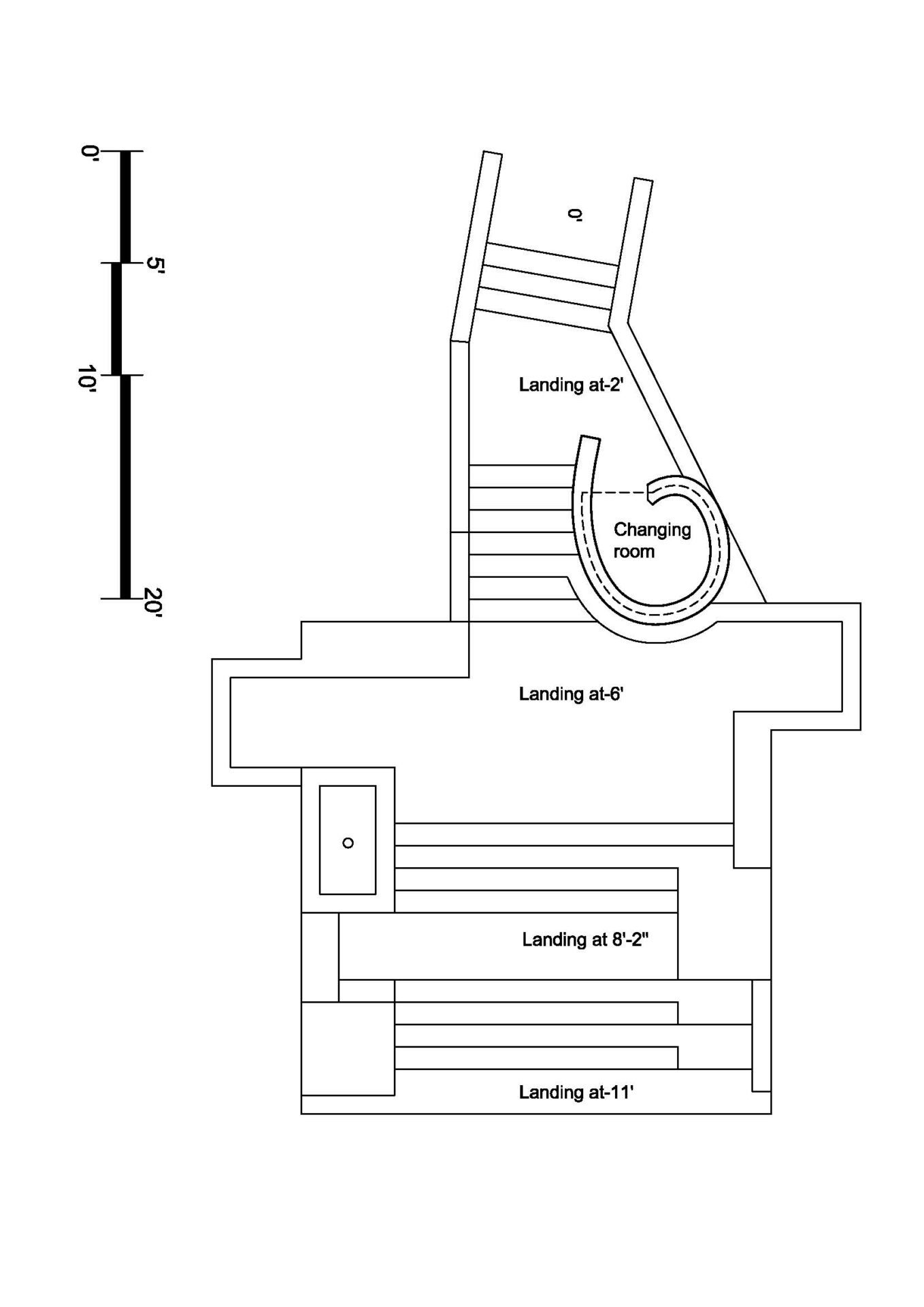

The smaller “community ghat” is directly connected to the water’s edge via a few steps. Intended for and used extensively by one of the city’s largest low-income communities, where the majority are Hindu, it caters specifically to their needs in terms of bathing, washing and practising religious rituals, with a changing room and benches provided.

The architects surveyed and documented the trees in the city in order to propose ecologically significant vegetation and enhance the area’s biodiversity. All the existing trees on-site were preserved.

Mobilised by the community’s enthusiasm, Jhenaidah Municipality employed local craftspeople to execute the project, while the architects providing pro-bono consultancy services. The mayor reported that representatives of over 50 municipalities have visited to learn from these community engagement programmes.

As a result of rapidly growing populations across the globe, urbanisation has had a heavy toll on the quality and liveability of urban and rural spaces, and on the environment at large. A lack of urban planning and the sprawl of informal housing have left many urban and semi-urban communities without public spaces for social interaction or quality living, and with degraded environments, thus deepening inequalities and the marginalisation of poorer communities. This is especially the case of riverbank spaces in Bangladesh.

The ghat is built on two levels connected by stairs and a ramp, which provides access for people with disabilities.

By way of a lengthy and consistent community-driven process, led and created by the vision and leadership of committed designers and social workers, the Urban River Spaces project managed to rally local governance actors and inhabitants, and act as a catalyst to drive change in similar urban contexts in the city and beyond.

The project is part of a broader initiative in the town to provide decent housing in informally built areas, which led to a change of paradigm in urban governance, in Bangladesh and beyond, to create a long-lasting impact on people’s lives and the environment.

The ghat has become a popular place for the local people to exercise, enjoy an evening stroll, meet with friends or simply sit by the river.

Through consistent community participation and appropriation, extensive involvement of women and marginalised groups, and a local workforce, the seemingly simple undertaking of cleaning up the access to the Nabaganga river in Jhenaidah led to a thoughtful and minimal landscaping project with local materials and construction techniques, thus transforming a derelict informal dump site into an attractive and accessible multifunctional space that is valued by Jhenaidah’s diverse communities.

Smaller ghats are built to accomodate the daily needs of the local communities who bathe, wash their clothes and fish in the Nabaganga river.

As such, the project managed to reverse the ecological degradation and health hazards of the river and its banks, and induce effective ecological improvement of the river, in one of the most riverine countries on earth.

View of the small ghat used by the inhabitants of the community of Shatbariya. The cylindrical structure adjoining the stairs is a changing room.

The Urban River Spaces project in Jhenaidah is one of a transformative nature that rallies all segments of local actors and communities to achieve the collective endeavour of reclaiming the commons and regaining connection with the river, including for ritualistic, functional and recreational purposes, with each participant and user having a strong sense of ownership.

Project Data

CLIENT: Municipality of Jhenaidah, Bangladesh: Saidul Karim Mintu, mayor

ARCHITECTS

Co.Creation.Architects, Jhenaidah, Bangladesh:

Suhailey Farzana, Khondaker Hasibul Kabir, co-founders & architects

STRUCTURAL ENGINEERS

Kamrul Islam, structural engineer

Md. Rashed Ali Khan, structural engineer

SUPPORTING ENTITIES

Citywide People’s Network, Jhenaidah, Bangladesh:

Khan Mohammad Abdullah, Rahabir Ahmed, Towhidul Alam, Khwaja Fatmi, Babul Hossain,

organisers and co-designers

Platform of Community Action and Architecture (POCAA), Dhaka, Bangladesh:

Mahmuda Alam, Rubaiya Nasrin, Nazia Roushan, Emerald Upoma Baidya, co-founders and

co-designers

On the lower level of the public ghat, the vertical surface of the retaining wall cleverly serves for public exhibition purposes.

Community Architects Network (CAN):

Chawanad Luansang, Supawut Boonma- hathanakorn, co-founders and co-designers

Asian Coalition for Housing Rights (ACHR), Bangkok, Thailand:

Somsook Boonyabancha, co-founder and co-designer

PROJECT DATA

Site Area: 4,267 m2

Built Area: 1,632 m2

Cost: 164,280 USD

Commission: 2018

Design: 2018

Construction: 2018–19