A Window into Art and Conflict

As part of the Education City Speaker Series, held in collaboration with VCU and VCUarts in the US, artists, and creators discussed how art can open windows to the world and into our own selves. SCALE speaks to Zayna Al- Saleh at length on the topic of art and conflict and their interlinking intersections.

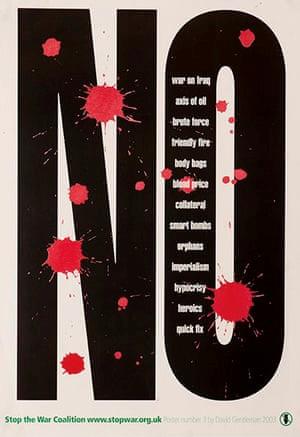

SCALE speaks to Zayna Al-Saleh, a British Palestinian art dealer, curator, activist, and arts journalist who operates independently. She consults for collectors privately and deals from art studios, galleries, and the secondary market. Her activism finds its roots in her Palestinian heritage. She most recently researched and curated ‘NO! 20 Years of Stop the War, A Visual Retrospective’ (September 2021), which surveyed the artistic output of the British anti-war movement. The exhibition comprised of diverse mediums and styles; shock-value placards, stitched banner work, textile art, music, film, photography, prints, paintings and site-specific installations. The works were culled from the organisation’s archives and wider artistic collections and included the recurring blood-splat placards by David Gentleman, Vivienne Westwood’s calico prayer flags, and satirical anti-Trump placard originals, now produced in a limited giclee series for this exhibition. She is in the process of co-founding an advisory with a majority focus on activist art.

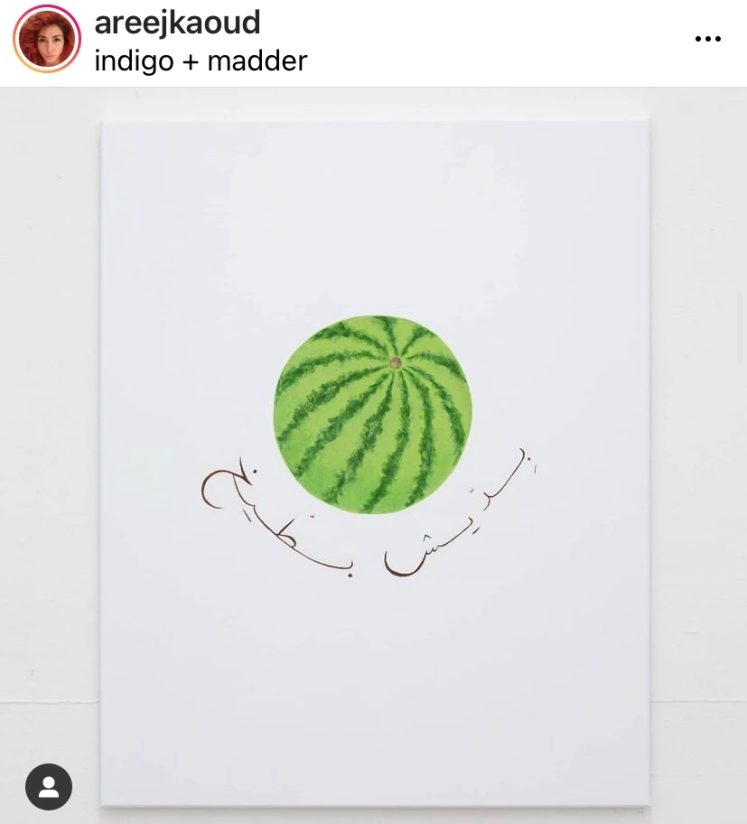

The image of the artwork by Areej Kaoud sourced from her Instagram called Bideesh Batteekh translating to watermelon or in coloquial Arabic, ‘I don’t want Bullshit’.

SCALE: In your work as a journalist and a curator tell us about the works that you have come across that are a result of a conflict?

ZAYNA: Conflict manifests in art very dynamically; the approach could be investigative, hypothetical, a form of protest, counter-censorship, preservation, brutal realism, satire, and so on. The oeuvre of Palestinian artist, Areej Kaoud, centres around response to emergency and long-term crisis, censorship and its subsequent anxiety. Banal phrases meant as safety provisions in imagined disaster scenarios, ‘It’s okay and it’s not’, ‘Control yourself’, were illuminated in LED lights on a panel for her series, ‘Silent sirens’ (2018). Her performance at Tate, ‘I Censor’ (2018) staged the contemporary paranoia of eavesdropping when the words she spoke were projected onto a screen in real-time, no matter the mundanity of the subject matter. In May 2021, Lebanese artist, Diana Al-Halabi and co-artists at Netherlands’ Piet Zwart Institute (PZI) protested against the forced expulsions of Sheikh Jarrah residents and were quickly met with orders to stop. The protest evolved into an impromptu performance during which the artists held a watermelon painting accompanied with the cursive text rooted in Magritte, ‘Ceci n’est pas une watermelon’, which was later seized. Al-Halabi’s MFA graduation project continued the sequel of art as resistance, featuring a performance of a fictional Palestine solidarity statement made by the Dutch arts institution and a film ‘On Scales of Violence: How to Measure A Dictator’. Her film investigates cognitive scales: women as dwarfed into a child’s gaze while the dictators and patriarchs appear exaggerated, later interrupted by popularly shared images of Israeli aggression as these events were unfolding in the midst of her writing and research. With censorship in mind, she concluded that dictatorship had in fact manifested on her campus in the form of institutional violence. In ‘Hungry for Home’ (2018), Samah Shihadi memorialises the Palestinian household in her depictions of dinner-table dialogue, harvesting, culinary heritage and agricultural practice.

SCALE: What impact does art create in shaping stories during conflicts? What was its role in expressing human feelings during such times?

ZAYNA: Art is imperative during conflict and its respective protest movements. I recently curated, ‘NO! 20 Years of Stop the War, A Visual Retrospective’, which brimmed with visual cues of the British anti-war movement. February 15 2003 marked the biggest protest recorded in British history when London mobilised against the war in Iraq. Ahead of this protest, Stop the War sought to promote uniformity in anti-war messaging by distributing one style of placard. The placards were designed by British artist, David Gentleman and depicted blood drops amidst the text ‘NO’. The photographs that emerged of that march were almost surreal; a crowd of two million strong beneath London’s landmarks and mist with NO placards in hand. The expression of solidarity is a beautiful thing but the overriding ambition is the wider context: creating an anti-war majority in this country.

Prior to his worldwide fame, Banksy produced stencil sprayed placards, ‘Yellow Chopper’ (2003), ‘Bomb Hugger’ (2003), ‘Grim Reaper’ (2003) paired with texts ‘NO’ ‘FRAGILE’ and/or ‘WRONG WAR’ that his friends distributed to protestors that day (15 February 2003). Most of these were severely damaged or confiscated by the London Metropolitan Police. In 2003, Banksy also sprayed one of his most notable anti-war images, ‘CND Soldiers’, outside the Houses of Parliament during an anti-war protest. These images were later produced into highly desirable printed editions.

David Gentleman’s installation (2008) of prints that depict 100,000 blood drops were pegged to the grounds of Parliament Square to depict the Iraq war death tolls up to that point.

Scottish artist-poet, Robert Montgomery, who famously detailed Iraq death tolls on Shoreditch billboards, hung his text installation at the 10th Anniversary protest against the war in Afghanistan in 2011. The banner read:

‘When we are sleeping, airplanes carry

Memories of the horrors we have given

Our silent consent to into the night sky

Of our cities, and leave them there, to

Gather like clouds and condense into

Our dreams before morning’

These artists, who in my opinion are the pride of our country, have shaped national consciousness in a way absent from other artistic practices.

SCALE: It is said that any creative work is a result of conflicts. The role of conflict, within and with others is evident when inflection points of creative careers are examined. Do you agree with this?

ZAYNA: To an extent. But this is not true across the board, especially in the unforgiving context of war because of the simple fact that conflict potentiates unnecessary loss of life. Take Samar Alhallaq, an artist working on the Palestinian History Tapestry (PHT), who was killed in an Israeli airstrike along with her two sons and unborn child. I think we tread a very thin line when we talk about war and art-making as we cannot glamorise the catalyst for these works by deeming conflict as the primary – and sometimes – the only drive.

PHT is a not-for-profit, UK project established in 2012, that seeks to support the Palestinian narrative in the medium that defines it. The project relies on a thriving network of artists and embroiderers, a large number of which are women: some live and work in the refugee camps in Lebanon and Jordan, while others are based in the West Bank, Gaza, and Israel.

But before I begin on the subject of Palestine, it is important to note that one of the organisers behind the Palestinian History Tapestry, Lady Jan Chalmers, also played a key role in the Keiskamma Art project which was established in 2000. The objective was to train the local Xhosa women in embroidery who later went on to create a 126-metre long Bayeux tapestry. This tapestry, comprised of several stitched panels, was driven by academic research and first-hand accounts from village elders, and bridges the San and Xhosa narrative from British and Apartheid rule to Mandela’s release from prison. It now hangs in the South African parliament in Cape Town.

SCALE: Do you think the lockdown and Covid time have helped the creativity blossom in many?

ZAYNA: Iraqi artist, Maysaloun Faraj, immediately comes to mind. I have been working with Maysaloun closely on her HOME series that was born out of the covid-19 crisis. The stay-at-home orders meant we all became far more connected to the visual aspects of our interiors. Maysaloun depicted her interiors in paintings of acrylic, oil, and oil pastels, in diverse perspectives and tonalities, but also translated many of her own works – from ceramics, sculpture to painting – that were displayed in her home in a fresh pictorial grammar. Her optimistic palette contradicted the widespread mood and urged us to make peace with our predicament. This series evolved into commissioned paintings of the interiors of art patrons and collectors on an international level, and has recently begun scaling up the size of these works.