Yee I-Lann: When Hugs Become Language, and Mat Becomes Power

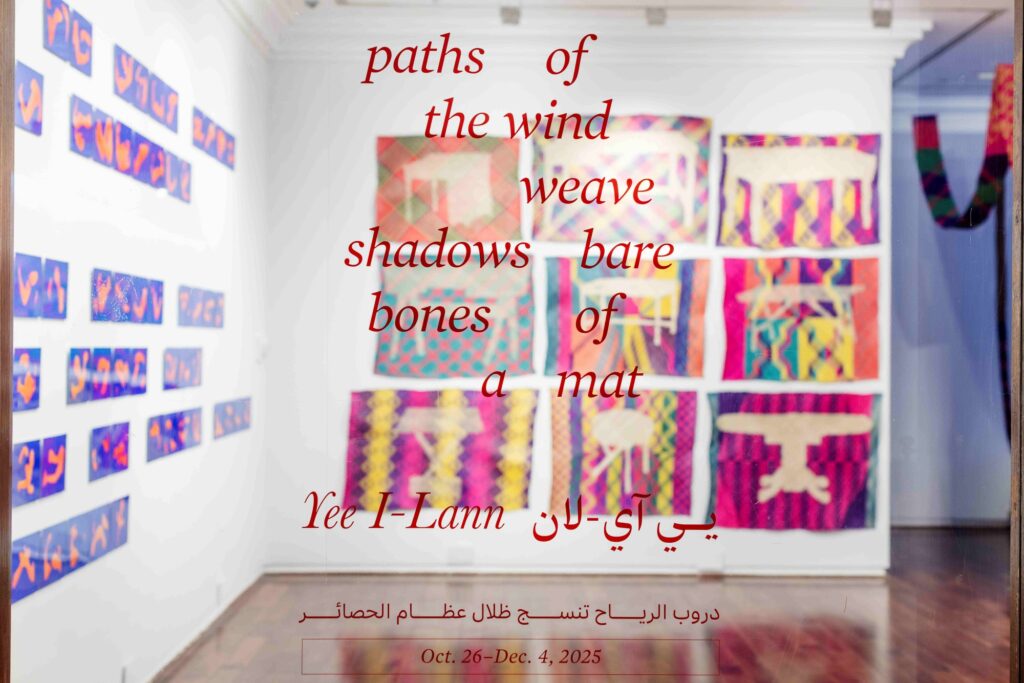

The title of Yee I-Lann’s exhibition, paths of the wind weave shadows bare bones of a mat, appears at first like a line of poetry resisting grammar, resisting order. But it is, quite literally, much more: it is a sentence woven from human embraces. Her work that throws a joyful glow over the walls of The Gallery at VCUarts Qatar is a burst of colour on hand-woven mat, work that throws light on the shocking reality of a tradition-strong-community that does not exist on paper. By Sindhu Nair

Yee-I-Lann giving the keynote lecture at the opening of the HBK Symposium of Islamic Art 2025

Malaysian interdisciplinary artist Yee-I-Lann was the keynote speaker at The 11th Hamad bin Khalifa Symposium on Islamic Art that concluded in the first week of November 2025 at VCUarts Qatar. She spoke on “The Surface Remembers: Decolonial Groundwork from the Archipelago”, as she explored Southeast Asia’s layered histories and the role of collective making in resisting colonial narratives.

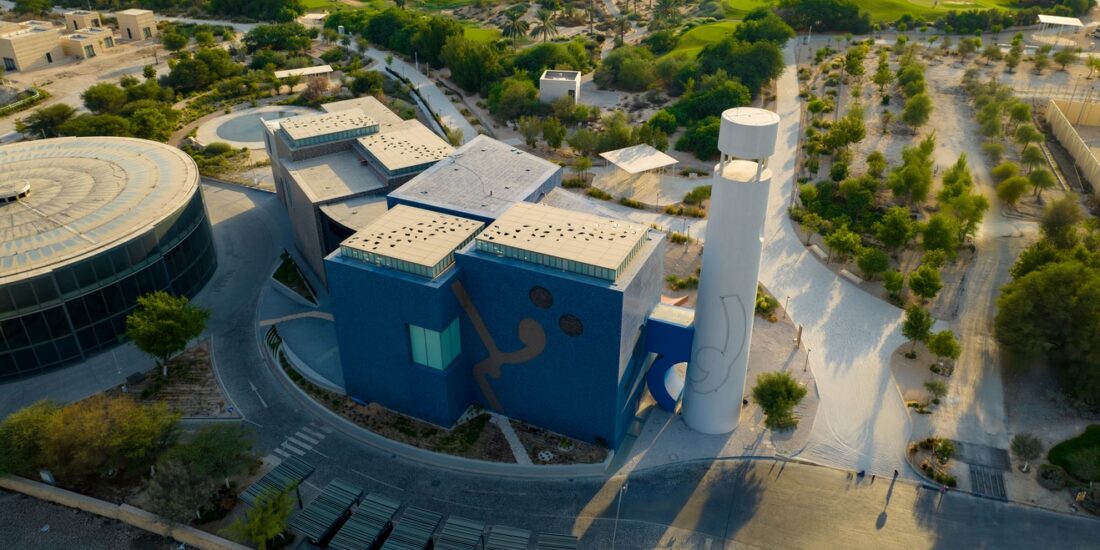

The Gallery VCUarts Qatar.

Her accompanying exhibition, paths of the wind weave shadows bare bones of a mat, opened the same week at The Gallery at VCUarts Qatar and remains on view to the public through December 6, 2025. The exhibition invites visitors to consider materiality, language, and power through community collaboration. The exhibition is curated by artist and educator, Head of Gallery Chase Westfall and Associate Curator of Special Projects, Meriem Aiouna, of VCUarts Qatar.

The title is borrowed from one of her featured works, part of the long-evolving Rasa Sayang series, in which Yee transforms photographs of hugs into coded alphabets.

paths of the wind weave shadows bare bones of a mat through hugs

Yee made an open call to people to donate hugs and she, along with her assistant walked around the market place and asked people if they would hug and then take pictures of the hug, without their faces.

“What I do is, document the arms, I take out all the information and just the positive, negative information is left behind in a hug. A hug because, there is an energy transformation from one person to another. This is a physical thing when we hug and, in my work, I want to speak of this energy,” she says.

Each letter is shaped not by ink but by the space between two bodies holding one another. Arms, shoulders, the curve of a back, become the strokes of her script.

Images of hugs in calligraphy

“Look at the line between the blue and orange, it vibrates because your retina cannot hold complementary colours still,” she says. “That vibration is the energy of a hug — something moving between people.”

The exhibition title can be read in this language of embrace. A sentence written in the warmth of a hug. It is also an invitation to step into Yee’s worldview, to drop the rigidity of formal grammar and enter a space of shared humankind.

It is the first grammar Yee dismantled, the earliest doorway into her search for alternative systems of meaning, of resisting power plays.

Hug is the language of repair

Yee with one from the Rasa Sayang series, Digital inkjet pigment print on metallic paper.

The first chapter of The Hugs took shape in 2012, at a moment when the artist was reflecting on tensions between Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo Malaysia, two halves of the nation separated by the South China Sea. She describes wanting to “symbolically hug the two halves to come together, to return to our shared humanity.” The phrase formed through the choreography of bodies read: the sun will rise in the east and deliver us from this long night.

The project grew through participation. She received, as she puts it, “loads and loads” of hugs, donated by friends, acquaintances, and strangers responding to open calls on Facebook and WhatsApp. Some she collected herself in Kuala Lumpur and Kota Kinabalu. Hundreds of embraces filled her archive.

At first, she was simply drawn to hugging because she is, in her own words, “a hugger.” But as the material accumulated, she became increasingly interested in the shapes bodies occupy and how a viewer might read posture as one reads text.

“We already use phrases like body language and the body politics,” she explains, “so the work became a search for how those ideas could be visualised.”

She began editing the images, looking for the suggestion of letters. an H, a W, an S, until the forms could be read. Eventually, “once you get it, you can actually read the hugs,” she says. “It looks like calligraphy.”

For her, the hugs are a language of gathering and repair, a way of asking whether bodies can speak a political truth without uttering a word.

The Journey from Embrace to Mat

The TIKAR/MEJA series

If Rasa Sayang began as a tender gesture, a symbolic hug that called divided halves of Malaysia back together, it also marked the beginning of Yee’s lifelong interrogation of how people connect, and how they build meaning together. Hugs became typography; typography became poetry; poetry became a political question: What forms of knowledge do we honour, and what forms do we silence?

A year after Yee’s Hugs, in 2013, she attended what she describes as “a life-changing workshop” led by Dr. Alexander Supartono, an Indonesian art historian and photography scholar who curates exhibitions with artists from everywhere although primarily from the Southeast Asia region. Ten Southeast Asian artists spent days reviewing thousands of Dutch colonial photographs from the Tropenmuseum. As she looked and looked, she began noticing one object repeating across the images: “the table.”

Yee collaborates with indigenous weavers from Bajau Sama Di Laut communities in Sabah, Malaysia to create these brightly coloured tikar mats.

She had arrived with a question: How do you colonise someone? What’s on your to-do list? The answer, after ten days, unsettled her. “Not with a gun. With a gun, I shoot you and you’re dead—end of story. I’m going to colonise you with the table.”

The table, she realised, is where power reorganizes knowledge. “I will write your education system. I will write your history. I will draw your border. I will measure your land and its minerals. I will define you, and you will tell your children who they are according to me.” Colonisation, she understood, is not the erasure of memory, but “replacing knowledge with another system of knowledge.”

Language confirms it. “A seat at the table, crumbs from the table, bringing something to the table, tabling it in parliament.” Parliament, she says, is “the prominent table.”

The locally-woven mat provides a cultural and economic tie, uniting people divided by legacies of nationalism and displacement.

This insight deepened through her work with stateless communities: “They have rich cultures but no paper identity. They don’t exist on paper. They cannot go to a hospital or a school.” It was, she says, like seeing “the matrix of the world.”

Even the word itself holds the imprint of empire. In Malay, meja comes from the Portuguese and Spanish mesa. In Tagalog, it remains mesa. Across Southeast Asia, the very word for the object of power arrived with colonial ships.

Hugs and tables, two gestures, two architectures. One gathers bodies into care; the other arranges them into systems. Together, they form the tension at the core of her practice: the intimate language of connection and the structural language of power.

Finding the Mat: A Grammar of Egalitarian Power

The Tikar Reben is a 63 meter tkar “ribbon” that becomes a figurative bridge between neighbouring coastal communities.

Yee went through a period of despair when she discovered the army of tables, and this was just before she discovered the mat.

“The mat revealed itself in the everyday, in the local market in Sabah, a place where mountain people, sea people, and plains people met to exchange goods. A place where one sought not the familiar, but the other. Everything in the market rested on a mat,” says the artist.

The Tikar Reben connects divided communities.

The tikar mat, Yee realised, was not a domestic afterthought. It was architecture. It was philosophy. It was a social system, a pre-colonial platform on which communities gathered, traded, argued, mourned, celebrated.

“If the table is hard patriarchal power,” she says, “the mat is soft feminist power. It listens. It expands. It holds.”

This insight set her on the path to the Bajau Sama Dilaut community, the sea people of Southeast Asia, some of whom arestateless, paperless and yet their cultural heritage of weaving speaks of memory, rhythm, lineage, and resilience.

Through Roziah binti Jalalid, a Malaysian Bajau master weaver (who introduced Yee to the stateless community at Omadal Island) who is a key collaborator, Yee reentered a world that was completely different.

Working with them required Yee to abandon the very instincts that had shaped her artistic life. “I thought I had been collaborating all my adult life,” she says. “But I realised I had been acting like a table. I was dictating. To truly collaborate, I had to learn to be a mat: to listen, to absorb, to expand my understanding of knowledge.”

She tells the story of asking the weaving community for a test mat of a specific size, only to receive something different. When she asked why, the weaver explained that their measurements were not numerical but embodied. Lengths were counted using the lead weaver’s foot: life, death, life, death… always ending on life.

“It was so poetic,” Yee says. “Even the energy of the weaver becomes part of the mat.”

The Gallery at VCUarts Qatar

Through this process, she understood not only the philosophy of the mat but the philosophy of the people who weave it. And the collaboration deepened. Children were brought into the process. They mapped the island’s tables, the teacher’s desk at the school they themselves were barred from, the lectern mainly used only during elections, the hinged Quran stand, the kitchen table, the tiny floor tables used in informal schools for stateless children, and some tables that they imagined.

The transition from hugs to mats was not abrupt; it was organic. If hugs gave her a language of energy, the mat gave her a language of community, one stitched together through intergenerational intelligence, women’s labour, and the bodily memory embedded in woven pandanus.

Working with the Bajau Sama Dilaut forced Yee to unlearn the habits of the “table.”

Only when they spoke through these tables, and through the meaning of their mats, did the community fully enter the TIKAR/MEJA project, where the mat “eats” the table.

“A good table,” Roziah famously said, narrates Yee, “is one that listens to the mat.”

The TIKAR/MEJA which adorns the walls of The Gallery is colourful and intricate and yet deeply familiar and comforting for the messages it conveys.

Mat Logic as Conflict Resolution

Visitors experiencing the works of Yee.

In Doha, the exhibition takes on a new resonance, reflects Yee, who is forever looking for messages and lessons that are beyond the obvious and yet are so glaringly vital.

“We are an American university in Qatar,” Yee reflects, indicating “ A country currently deeply engaged in conflict resolution negotiations. How do you bring the ‘other’ together here? How do you share a mat?”

Her work offers no solutions, but proposes a shift: from hierarchy to listening, from rigidity to care, from single authority to plural knowledges.

Yee as the “&”

Yee & the TIKAR/MEJA

In our conversation, Yee describes herself as an aspiring “&”, the connective thread, the bridge, the conjunction that allows two worlds to meet without merging, without erasing difference.

Land & sea, Table & mat. Memory & future. Self & other.

Her art inhabits this in-between, the space where energy becomes language, where language becomes mat, and where mat becomes a site of resistance, comfort, and possibility.

To read her exhibition title in its hug-formed letters is to understand what the entire practice stands for: moments of exchange, shadow, memory, friction, breath. A syntax of feeling before form.

In Yee I-Lann’s world, power is not a table to sit at. It is a mat to be shared.

All Images Courtesy VCUarts Qatar

.