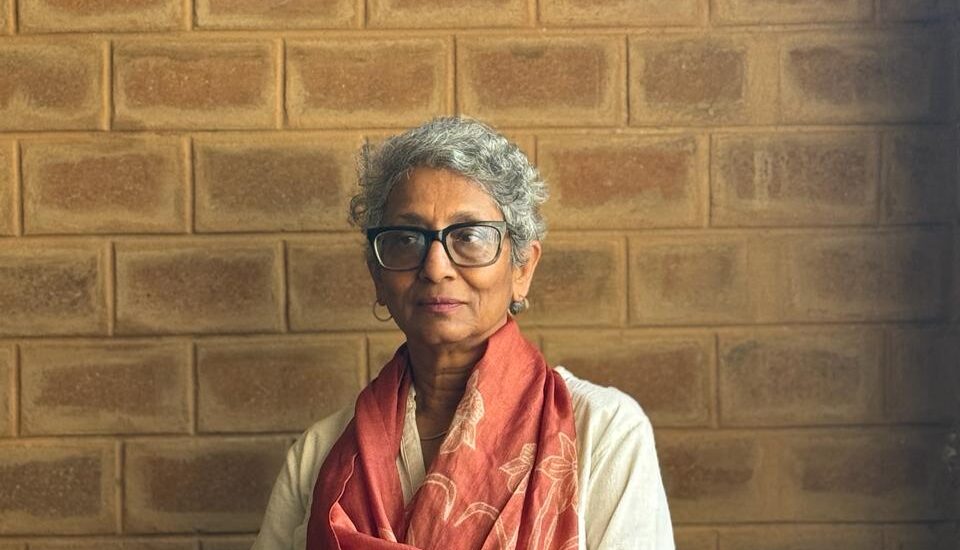

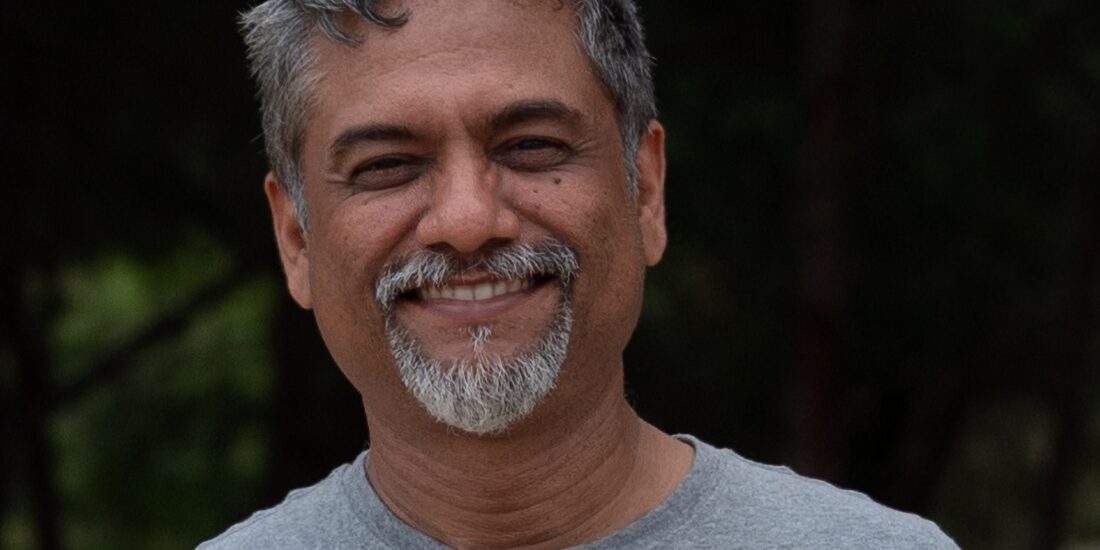

Building with Memory and Material: Masons Ink Studio

Architects Sridevi Changali and Rosie Paul have built Masons Ink Studio on a way of thinking that is as attentive to people, material and memory as it is to soil, lime and craft. Their practice is grounded in the belief that architecture must listen before it builds. It must listen to soil, to climate, to memory, to the hands that shape walls and to the communities who live with the consequences of design long after architects move on. By Arya Nair

Together, Sridevi Changali and Rosie Paul of Masons Ink Studio, offer a compelling reminder that the future of Indian cities may depend as much on remembering what we once knew as on inventing new methods. In this conversation with SCALE, they speak about the worlds that shaped them, the lessons found in forgotten techniques and the hope that anchors their practice.

Over more than a decade, they have cultivated a practice that dissolves the boundaries between research, construction, documentation, training, conservation and policy. Their work moves between heritage bungalows, earthen buildings, social housing clusters and community-led restoration projects, often beginning not with drawings but with conversations on site and with materials tested through touch as much as through science.

What distinguishes Masons Ink is not just its material intelligence but a quiet insistence that building is both a cultural and ecological act. In a landscape where speed, aspiration and convenience often overshadow local wisdom, Sridevi and Rosy choose the long view. They learn from older craftspeople, train younger ones, document processes so others can follow and design in ways that honour climate and context rather than fight them.

From one of the firms recent projects, Yash Farms.

SCALE: Could you share a little about your early lives and the places that shaped you both?

Sridevi: I am originally from Kerala, but I grew up in multiple cities. I studied architecture at Manipal and that is where Rosy and I met.

Rosie: I am also from Kerala, but my family mostly lived outside the state. My father worked in a government job, so we moved around a lot and I spent many years in Tamil Nadu. Growing up in different cultures shaped both of us in a good way. The foundation of the practice started as a shared curiosity rather than a formal plan.

Ra Maram located in Manchi reserve forest has been designed to align with the principles of cradle to grave concept, minimising the carbon footprint and embodied energy of the construction.

SCALE: What inspired you to start Masons Ink Studio?

Sridevi: The dream started when we were in college. During our night outs we would talk about starting something of our own just to stay awake. We did not really think it would actually happen, but the stars aligned and we started in 2013.

Rosie: Even in college, sustainability and heritage were the two subjects we were always excited about and they were the only classes we were always on time for. I eventually specialised in sustainability, especially materials and earth, and she moved into heritage conservation.

From the various second-hand yards that were scavenged for doors and windows to the innovative use of crate wood as furniture – every element was carefully hand-picked for this project called the Brickloft.

SCALE: How did study, research and hands-on training evolve into such defining pillars of your practice?

Sridevi: As we started working, the social aspect entered naturally. When you work with natural materials you work with communities and you train people and build capacity. We began collaborating with NGOs on social housing where every brick mattered and that became one of our verticals. From the beginning, because we started our careers at Auroville Earth Institute, training and knowledge sharing were normal to us. Learning, drawing and building always happened together and masons often knew more than we did as fresh architects. That shaped how we wanted the practice to be.

Rosie: A lot of things grew from experience. I did my post masters in earthen construction while we were already running the practice. Through my thesis we studied traditional non toxic additives and community knowledge that existed before cement. My academic time gave me scientific grounding and helped me understand materials deeply. That is how research and development became another vertical.

Sitting on a 1.2 acre organic farm, this Yash Farm structure’s material composition includes Compressed Stabilized Earth Blocks (CSEB), Rammed earth and natural stone.

SCALE: Cities used to feel distinct through local materials and craft. Now many places look similar. What is lost and can anything be done about it?

Sridevi: I come at this from heritage and urban conservation perspective. People think heritage is about freezing a place in time but that is not true. Pondicherry’s old town survives because value was placed on preserving its character and its heritage cell guided facade maintenance. If every city did that, regional characteristics would still be visible. Heritage and development can go together but it needs a top down approach where historic cores are protected and modern development is guided elsewhere.

Rosie: At the local area plan level many cities are already exploring form based codes that focus on context and character instead of only numbers. Our statutory framework already contains heritage provisions in planning acts. The real work is applying what already exists to how cities function.

A Management consultant’s workspace, an Artist’s studio and an Architectural practice – these three functions with shared facilities of reception area and seminar halls is housed in this 2500sft unit of the Courtyard Residence.

SCALE: With sustainability becoming a buzzword and many people assuming that a visible green feature equals sustainability, how do you respond to greenwashing and the current framing of sustainability?

Rosie: Sustainability becoming popular has a good side and a bad side. More people are asking questions, but the market also sees an opening and it becomes about marketing. Highly processed or harmful products get sold as green because people do not have the details.

Sridevi: As a practice we try to share correct information through social media, workshops, technical documents and international platforms. At the community level we see people converting climate responsive homes into concrete boxes because of marketing and then they suffer. Education at every level matters and policy change matters too.

The inside spaces seamlessly flow into the outdoors and vice versa through dual courtyards in this Courtyard House. The Seminar Hall has a beautiful earthen vault for a ceiling which is extremely environment friendly and needs no steel reinforcement. It will also keeps the room cool during the sultry summers of Kerala.

SCALE: When cities are building larger and more complex structures, is it possible to bring natural materials into that scale with confidence?

Rosie: The imagery around sustainability is often small houses because individuals adopt it first. Larger developers rarely ask for it, but that will change when more people adopt these materials. Natural materials can absolutely be used at scale if you understand how they work and design responsibly.

Sridevi: There are historical examples like Shibam in Yemen which has seven storeyed mud buildings. Scale is possible. The larger question is whether we even need so many towers because studies show medium and low density housing often perform better. Many towers sit empty because they were built for speculation. COVID showed how quickly needs change and we should rethink what we build.

The Courtyard House framed by courtyards and water bodies.

SCALE: Tall towers dominate city skylines today but do they genuinely serve the way people live and the kind of communities we hope to build?

Sridevi: People’s lives are constantly changing and density is not only about height. Cities are living systems shaped by how people move, work and form communities.

Rosie: Many towers rise not because people want them but because they represent aspiration. I have seen buildings that are half empty because they were built for investment rather than living. We need to ask what people actually need and plan with flexibility rather than assuming height equals progress.

The walls of the Ra Maram House are of stabilised mud blocks with the foundation and certain feature walls, being of local Sadarhalli stone, sourced and sized from within the site.

SCALE: Has any project fundamentally changed your approach to design?

Rosie: Our social housing projects changed us. Communities were already living sustainably out of necessity and that humbled our assumptions. We learned to simplify drawings because masons needed clarity not perfection. Many decisions had to be made on site based on how people lived.

Sridevi: In one project in Koramangala a corner allowed for a big window but when we returned it had been walled up because the resident needed a place for the TV. They left before sunrise and returned after sunset so daylight did not matter to them. We added a ventilator and respected their choice. It taught us that user comfort must come first.

Rosie: Beauty and practicality are not separate. A functional element can be beautiful because it serves people’s needs.

SCALE: In your experience which design decisions or site processes have the greatest impact on comfort and long term performance?

Rosie: We do not have one repeated signature detail. What you see across our work are passive design strategies like orientation, openings and ways for hot air to escape.

Sridevi: In a Ratnagiri project the client wanted our mud work but the local palette was quarry waste stone and lime. The older mason knew lime but had forgotten the correct process. We reintroduced the proper techniques and worked with the team. It leaked at first because the process had been forgotten, but with training the mason mastered it again and is now hired for restoration work. The transfer of skill mattered as much as the building.

SCALE: You often use reclaimed elements and nostalgic details. How do these pieces shape the way people experience your projects?

Sridevi: We use elements like oxide flooring, reclaimed windows and atimudi tiles because they evoke memory and emotion. Even details in our own office interiors trigger nostalgia.

Rosie: These details reconnect people to everyday rituals like sitting on a veranda while making tea and make spaces feel lived in rather than staged.

The Brickloft House has a bohemian touch with all its acquired artefacts.

SCALE: Why do previous generations who value tradition still often choose marble or tiles over local finishes?

Rosie: It is often about aspiration. Italian marble was once a status symbol even if it does not suit Kerala’s climate. Skills have also declined so when oxide is done badly it cracks and people blame the material. We try to bridge that gap through skilling and bringing artisans in.

Sridevi: No material is immune to bad workmanship and natural materials are judged more harshly. That is why expertise and early collaboration matter and why we bring specialists in from the start.

SCALE: How do you avoid mistakes and make sure the right expertise is on the project?

Sridevi: We do not work in isolation and involve permaculture professionals, energy experts and engineers early so technical concerns are addressed from the beginning. Rosy: The best time to bring an expert in is during planning, not after a mistake. It ensures the right decisions are built in from the start.

The Brick Loft House is a treasure trove of reclaimed materials.

SCALE: With artisans increasingly steering their children toward careers like engineering and medicine, what changes can ensure that traditional crafts remain a viable and desirable livelihood option?

Rosie: Many artisans want their children to choose other careers and I understand why. But skilled artisans who do good work are now booked months in advance, which shows the value of the craft.

Sridevi: Respect and fair pay are essential. If artisans earn well the social perception shifts. Training should also be open to newcomers, not just to children of artisans. Region specific guilds or builder schools could help.

Rosie: Skills have to be accessible and institutionalised so knowledge does not disappear. We have seen people trained on our sites go on to do similar work elsewhere.

Sridevi: It needs collective effort through sharing knowledge, fair economic models and supportive policy. Collaboration speeds change and we cannot do it alone.

SCALE: What policy or institutional changes would help sustain craft and replicate good practice?

Sridevi: Local area planning and form based codes can embed character in law. Our planning acts already include heritage provisions that could be activated.

Rosie: District level vocational centres or a national builders guild could teach local texts and region specific skills. Research funding and market demand are important for these systems to grow.

SCALE: Any final thoughts on what you hope to build with the studio?

Sridevi: Everything we care about has been folded into the studio whether research, workshops, teaching or documentation. We want knowledge to be accessible so others can build on it.

Rosie: An architect’s strength is knowing when another person’s expertise is needed. The practice grows when specialists and artisans come in at the right moment. We hope the studio stays curious, transparent and grounded in care and humility.

The Brick Loft House in Bangalore.

A Deeply Rooted Practice

Across their stories, Sridevi Changali and Rosie Paul reveal a way of practising architecture that is patient, attentive and deeply rooted in lived experience. Their reflections describe a discipline that listens closely to the mason shaping soil with his hands, to the rhythms of climate that have guided building for generations and to the communities who carry these environments forward in their daily lives. At a time when construction often prizes speed over intention, their work reminds us that lasting architecture is built through care, curiosity and a respect for the wisdom already present in the world.

Masons Ink Studio shows what becomes possible when architecture chooses continuity over novelty. In their work, the past is not a relic but a source of methods, materials and meaning that can be read again with renewed clarity. Their approach makes the case that sustainability is not a label or an aesthetic. It is a long practice of responsibility that begins in understanding the land, grows through the hands of skilled artisans and finds its purpose in buildings that continue to serve long after they are completed.

Their practice encourages us to pay attention to the ground beneath our feet and to the knowledge carried quietly within it. It asks us to design with intention rather than urgency, to collaborate with generosity and to remember that the choices we make today will shape how future generations experience place. In that sense, their architecture becomes more than the making of structures. It becomes an act of stewardship and an invitation to honour the memories and relationships that allow those structures to matter.