On the Sustainable Path

Professor Eugene Pandala crafts beautiful structures that are sensitive to the local conditions with materials that have a precedent in traditional architecture.

In these prevalent times of landslides and flooding in South India, the reasons of which is attributed to the major ecological imbalance caused by the destruction of the Ghats and the rampant construction along coastlines, it is time to step back and look at construction methods that do not destroy the earth’s innate stability.

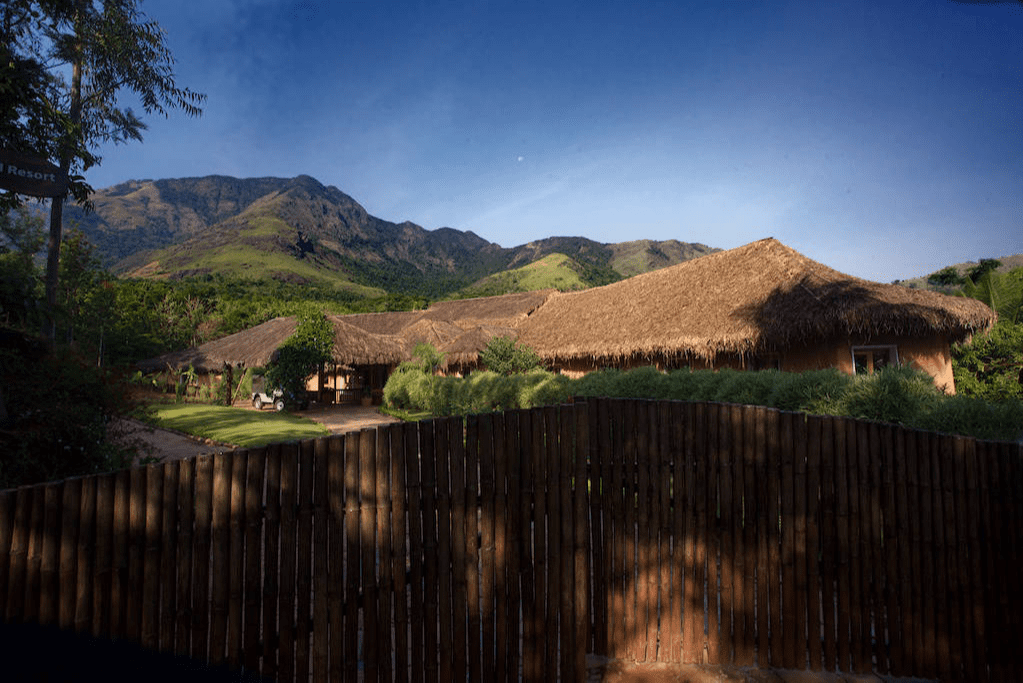

A visit to Banasura Hill Resort in Wayanad, Kerala spread across 35 acres of verdant terrain tucked away at an altitude of 3500 feet above sea level, is enough to urge one back to nature and buildings that celebrate the environment. Termed by BBC, as Kerala’s mud haven, this resort is constructed using mud excavated from the very site that it stands on. The structure is an architectural delight to the senses, stunning in its organic beauty, ingenious in its construction methods and extremely comfortable to live in with high ceiling heights and cool rammed earth walls.

“Old mud structures have survived ages of seasonal changes and I am only continuing the age-old-proven-technology.”

Professor Eugene Pandala, the mastermind behind this and many such vernacular architecture buildings, from award-winning resort projects to creatively designed residences, does not think that he has painted a brilliant stroke, instead, he feels he has just followed the examples set by the indigenous builders of earlier times.

Prof Eugene’s buildings are an inspiration, each of them built from and for the site and the environment it is set in. They are built using local, low-cost, plentifully available materials. His buildings have a deep relationship with nature, they are climate-friendly and do not stand out as an eye-sore instead meld with the local setting. Prof Eugene is involved with various important government-funded urban design and heritage conservation projects including Trivandrum East Fort conservation and Fort Cochin Renewal and beautification project. His designs of hamlets for the rehabilitation of tsunami victims at Kollam and Alappuzha districts of Kerala was widely appreciated due to its interwoven complicity with nature. In 2011, the Lalit Kala Akademi conferred him with the first Laurie Baker Award for his work in sustainable and cost-effective buildings.

Raviz Ashtamudi is a five-star deluxe hospitality project located in the heart of Kollam City, abutting the famous backwater Ashtamudy Lake.

But how do buildings made from materials perceived to be not as strong as concrete survive the harsh monsoons now prevalent in the southern states of India? The architect is quite confident when he says, “Old mud structures have survived ages of seasonal changes and I am only continuing the age-old-proven-technology. It also depends on the placement of the building in such a way that there is no risk involved for the building. The disaster that we see today is because the buildings were not placed optimally on the site or because they were built on zones that were not meant for construction. The state needs a proper zoning law that should be put into place.”

- Revathy Kalamandir Film Academy project was initiated in 2003, first conceived as a film studio. The project was partially done by 2005, and was on hold till 2012, later was converted as a film academy.

After his bachelor studies in architecture from COE, Trivandrum, Prof Eugene did his Masters in Urban Design at the School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi. But his inspiration came from reading the works of Egyptian architect, Hassan Fathy, specifically of the book titled, Architecture for the poor and later on with an opportunity to meet him and listen to his inspiring talks during his visit to his School in Delhi.

“That book triggered my interest in vernacular architecture,” says Prof Eugene, “I started looking around and found that I was surrounded by such buildings, not only in Kerala, but also outside the state. Even the hostel I stayed in Trivandrum while I was studying for my bachelors, the old east fort area and, important public buildings, all of which used the most basic of materials and have survived the advent of time and weather.”

He says that inspiration was all around. “Once I began observing, I began learning, experimenting. But I had to wait till 1994 for a good client who was willing to go with this technique and gave me a free rein to implement my desire to build with mud,” he says.

Bodhi House was the first residential project that allowed him to design with the material Prof Eugene wanted to use, mud.

- Features like the windows and lintels have all been conceptualised and realised in a cost-effective manner.

His first work called the Bodhi House won accolades and broke many conventions and prejudices. Mud houses which were seen as houses for the poor were built for this couple, who were brave enough to take the path less trodden. This particular house was built from mud, sourced from an excavation of an irrigation canal. He used the cob technique, one of the many methods of employing mud. Traditionally, a cob structure contains a mixture of sand, clay, and straw blended with water.

It was not only mud architecture that he was interested in, but he also wanted to use materials found in abundance at the site he was building in. “Good quality mud is not available everywhere. I am currently building a resort in Madhya Pradesh where we are building with timber and a project in Assam with bamboo and mud.”

He feels that resort projects give architects an opportunity to exhibit materials that are not typically used in the construction.

“Nature is my greatest inspiration,” he says. “I don’t wish to create magnificent structures that stand out in the location they are placed in. I love building structures that embrace the surrounding so that the balance of nature is not forfeited. That is why I like curved walls and organic shapes and materials that mimic nature.”

THE MUD MAGIC

Banasura Resort in Wayanad was a ground-breaking project in many ways; it was a project that was recognized for its eco-tourism, for the innovation in construction and for the material used. Prof Eugene remembers the path that led to this venture, “The owner was a software engineer and he wanted me to build a resort in this beautiful property near the Banasura Dams in Wayanad. When I visited the site, absorbed the beautiful setting and inspected the soil, I was quite sure that I did not want to disturb the beauty of the landscape. The next step was convincing the client which took some time, but then the final product was worth all the efforts put in.”

Tendu Leaf is a boutique resort, abutting river Kent is a one-hour drive from Khajuraho. Panna wildlife sanctuary is just three hundred meters away.

The main lobby of the resort is a large expanse of space where the roofing is beautifully completed in steel composite truss and covered in bamboo, not unlike older buildings you would find in Wayanad. The walls are built with rammed mud that is excavated from that area itself in preparation for the site. Prof Eugene has a foolproof method of testing the strength of mud, which is based on his vast experience with the material. “I have a simple method and I teach this method to my interns.”

He says, “I do not encourage mud architecture in Kerala now because of the restrictions in sourcing the material and also the lack of good mud. It is indeed a sad state of affairs when it is easier to make cement or concrete blocks made of granite mined from the Western Ghats, using intense energy, than it is to source mud in Kerala.” He also says that the cost of labour has become so high in Kerala that it is not justified to spend so much on mud architecture. But he is currently building mud and other sustainable projects outside the state, where sustainable resources are available and labour cost is much more affordable.

Prof Eugene was asked to build a mud house by a client in Trichur but he had to modify his technique as the site was filled with granite stones, so he used that instead. “I used mud as mortar with stones from the site.” “I used mud as mortar with stones from the site.”

- The main two-storey structure that spans 20,000 sq.ft, is built around a central nadumuttom or courtyard. The ‘rammed earth’ style of building walls that mixes sand along with 5% cement was used in the construction of the walls of this building.

The embodied energy required to construct buildings and sustain them with modern comforts, demands nearly 30- 40 % of the energy that we produce from fossil fuel. In 2015, 50% of the world’s population lived in urban areas, and carbon emission was 76 %. It is projected that by 2050, three-fourth of the world’s population will move on to cities. Urban area. The buildings and construction sectors combined are responsible for 36% of global final energy consumption and nearly 40% of total direct and indirect CO2 emissions. The sustainable building should be about reducing this energy usage, believes Prof Eugene. He scoffs at the “Industry controlled, Green Building rating systems,” he says, “These supposedly “green” buildings are five times more expensive to construct than a normal building, they then cease to be sustainable for the common man.”

He also says that traditional building technologies do not need LEED or IGBC certification to prove itself, they are sustainable can easily overtake the certified buildings in a qualitative analysis with sustainability points if we compare the points. Moreover, these simple, age-old tradition can be implemented with minimum energy and requires simple technologies which are simple and can be explained to anyone with brief training.

Prof Eugene believes that the climate change crisis is very real and not a hoax and all humans need a lifestyle modification to mitigate the crisis.

“We should all begin this process from our homes and extend it to where ever possible.”