Conservation is part of the building process

Conservation is part of the building process

The National Museum of Qatar to house many artefacts that showcases the rich past of the country.

Qatar Museums (QM) has revealed details of its expansive project of conserving and restoring the objects and artefacts that contribute to the immersive experience of this new museum, which showcases the country’s past, present and future.

The museum tells its sweeping story in three chapters — Beginnings, Life in Qatar, and Building the Nation — presented in eleven permanent galleries. Each gallery is an encompassing environment, which tells its part of the narrative through a creative combination of elements such as music, storytelling, archival images, oral histories and evocative aromas. Designed as distinctive experiences, these environmental galleries also contextualise an impressive array of archaeological and heritage objects, manuscripts, documents, photographs, jewellery, and costumes.

Dr. Haya Al Thani, Director of Curatorial Affairs at the National Museum of Qatar, said, “We have worked with teams of experts from Qatar and around the world to restore, protect and preserve each of the objects at the National Museum that help tell the overarching story of Qatar, its people and our place in the world. Although the National Museum focuses on creating an immersive experience using a variety of techniques, authentic objects are indispensable for connecting visitors to Qatar’s past. We have worked painstakingly to bring them back to life.”

Dr. Haya Al Thani, Director of Curatorial Affairs at the National Museum of Qatar, said, “We have worked with teams of experts from Qatar and around the world to restore, protect and preserve each of the objects at the National Museum that help tell the overarching story of Qatar, its people and our place in the world. Although the National Museum focuses on creating an immersive experience using a variety of techniques, authentic objects are indispensable for connecting visitors to Qatar’s past. We have worked painstakingly to bring them back to life.”

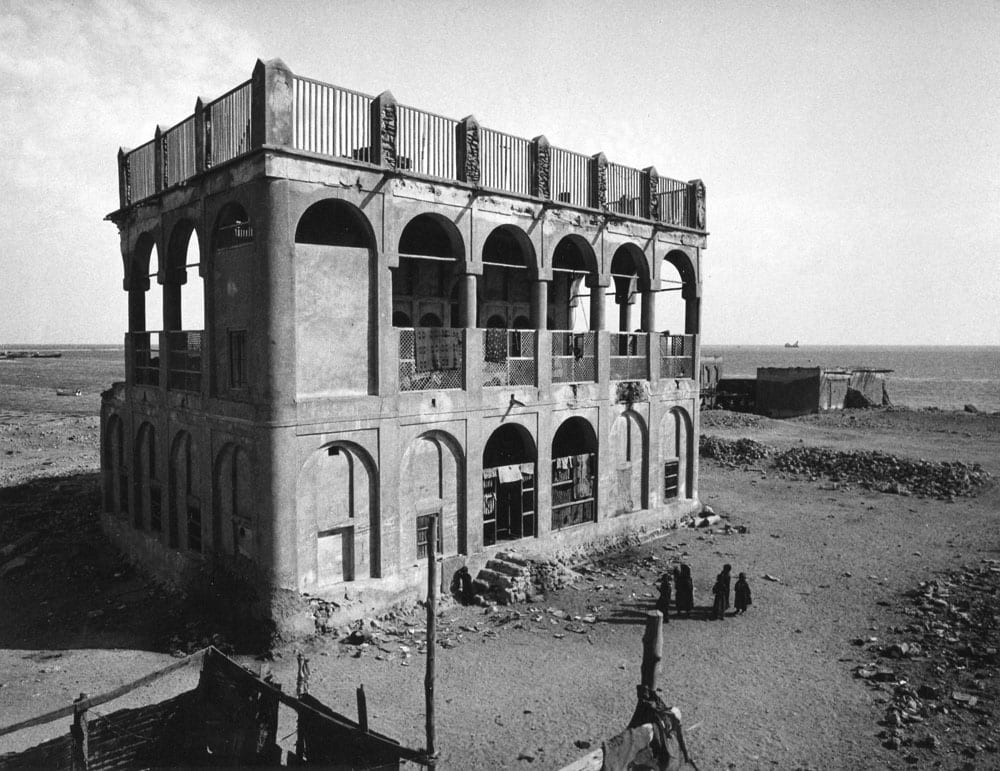

The largest and most impressive of these authentic artefacts is the building that housed the original National Museum, and that now sits at the heart of the new NMoQ: the palace of Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim bin Mohamed Al Thani. QM fully restored and protected the Palace before construction began on the new NMoQ.

One of Doha’s most recognisable landmarks, the palace serves as a monument to a historic way of life in Qatar. It was restored and refurbished numerous times since it was built in 1906, which meant that the expert team for this new conservation project had to peel back the layers of previous work to unearth the splendour of the original design. Another challenge was posed by the age of the palace and its location so near to the shore, which make it susceptible to cracking. To prevent further damage, architects placed concrete piles underneath to support the structure once the water table was removed. To fulfil this ambitious brief, Qatar Museums engaged specialists focusing on the development of sustainable building solutions using natural building materials.

One such artefact that has been conserved is a pearl merchant’s chest from the 19th century. The object was block lifted from the excavation site at Al Zubarah, meaning it was taken from the ground with the surrounding soil due to the fragility of its condition. It will now be one of the highlighted pieces in the displays about Al Zubarah archaeological site.

One such artefact that has been conserved is a pearl merchant’s chest from the 19th century. The object was block lifted from the excavation site at Al Zubarah, meaning it was taken from the ground with the surrounding soil due to the fragility of its condition. It will now be one of the highlighted pieces in the displays about Al Zubarah archaeological site.

Al Zubarah site yielded another object of great significance that will be on view at the NMoQ: Al Zubarah Quran, which is the oldest Quran created in Qatar and was written in Al Zubarah at the beginning of the 19th century by Ahmed bin Rashed bin Juma bin Helal Al Muraikhi. The final page of the Quran bears the location of Ahmed’s birth, which was the city of Al Zubarah, indicting the city’s importance in the development of religious scholarships at the time. The two-year-long restoration process on the Quran was overseen by QM’s team at the Museum of Islamic Art, who discovered that an older Quran had been used to create the cover for Al Zubarah Quran, as one of the approved ways of utilising older or damaged Qurans. A decision was taken to create “windows” on the cover to allow viewers to see the craftsmanship of the older Quran as well.

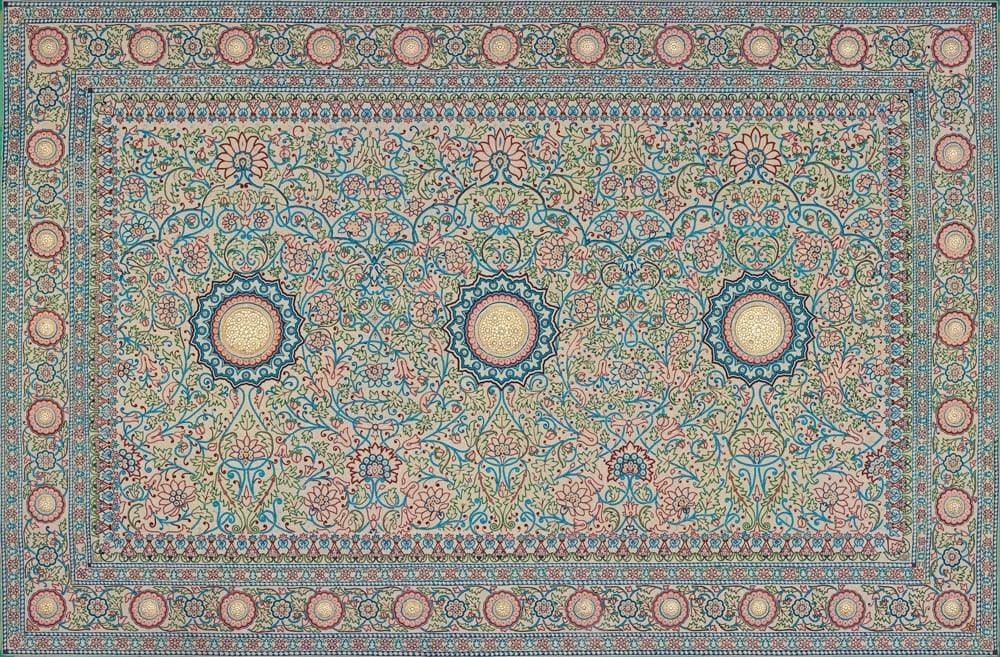

Pearl carpet of Baroda

One of the most spectacular artefacts in the NMoQ collection, and a testament to the flourishing pearl-trade relations between the Indian subcontinent and the Arabian Gulf, is the Pearl Carpet of Baroda. Commissioned by the Maharaja of Baroda in 1865 to adorn the tomb of the Prophet Mohammed (PBUH), the carpet has long been considered a remarkable work of art. Embroidery was a prevailing tradition in Baroda, and artists who specialised in textile art were welcome at the Maratha court. This was also the case for jewellers and gem cutters as they were commissioned to create gifts that were presented by the Indian rulers to their visitors. Their love for jewels, long tradition of gift-giving and favourable financial circumstances enabled the lords and Maharajas of Baroda to create astonishing art pieces, including the beautiful Baroda carpet.