The Light from Within

Sunitha Kondur and Bijoy Ramachandran, founders, partners in life, and at Hundredhands see themselves as architects who don’t work on projects to make a statement. Architecture for this firm is the making of places for well-being — as a backdrop for life. By Sindhu Nair

“Social distancing and work from home, inherently inhibit the way we work as people. It is incredible to even consider a future where public congregation is prohibited, both reflecting on our human impulses, and our democratic ideals.”

Bijoy Ramachandran

Founder/Architect

Hundredhands

When Bijoy Ramachandran, architect, urban designer, and founding partner at Hundredhands in Bangalore, spoke at the Frame Conclave held in Goa last year, he guided the audience through his personal story. The story of the defining moment as he walked through the Pritzker award-winning architect, Prof. B.V. Doshi-designed IIM. It could perhaps be his respect and admiration for Doshi, and it surely was a love for architecture, that made his words touch a nerve. It could also have been the drama of the particularly dark auditorium with a spotlight on the speaker, though I like to believe that Bijoy’s face seemed to be lit with a deep sincerity that made everyone sit up and listen. If you know Bijoy personally, you would recognize this luminosity in his eyes as a constant. He takes up each project, each job at hand with the same passion as he took us on his journey through the building that seemed to have been instrumental in shaping his architectural sensibilities, of course, honed by his zealous reading. Here is an excerpt from his speech about that particular building that evoked similar feelings of engagement in many architects of our generation, an almost visceral sensation as Bijoy explains: “We were in some sort of liminal space, not yet inside, making our way very slowly. Time seemed to stretch and our passage seemed gradual, elastic. Here was something new, something we had never seen before, yet in our bones we recognized it, it reminded us of something ancient, a memory buried deep in our consciousness.”

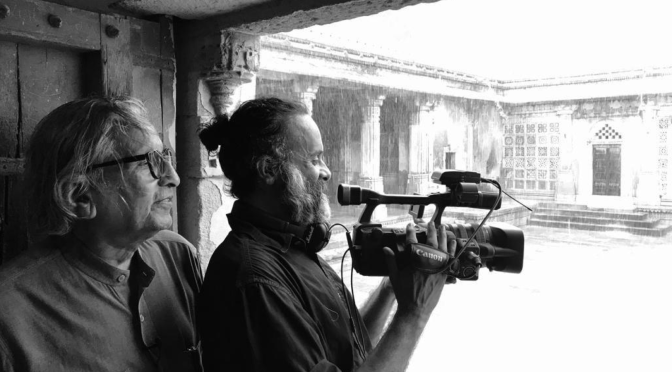

From being an ardent lover of Prof. Doshi’s spaces to producing a movie on him with his brother Premjit Ramachandran, Bijoy has come a long way on his journey of making places of well-being, and he believes that the two films he made with Prof. Doshi are the most important work he will probably ever do.

But in my mind’s eyes, I see Bijoy as a writer as well, someone whose masterpiece is yet to come, be it prose or architecture, something which is, as Gaston Bachelard says, “…that explodes at the centre of our being, releasing to the surface the debris of recognition”, an extract that Bijoy uses to describe the IIM building.

SCALE had a deeply engaging conversation with this architect, about his practice, his ideals, how he maintains the family-work balance, his childhood days in the Middle East, and why he chose to come back to India after his master’s degree in architecture and urbanism from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge.

The Bangalore International Centre designed by Hundredhands is a cultural facility that houses a 300 seat auditorium, seminar rooms, a library, a gallery, a restaurant, and guest accommodation.

SCALE: You have tried to encapsulate your practice in words like pragmatic, slow, and all-inclusive? How would you like to be known — as proponents of all the above or any in particular? And what do you mean by slow practice?

The wonderful architect, Graham Morrison, of Allies and Morrison, talks about an ‘Architecture without Adjectives’. We are seeking this in our work – a refined obviousness, perhaps. Our work is the combination of both a critical resistance and accommodation. We see ourselves, both as antagonists and service providers, as David Chipperfield refers to in his book Common Ground: a critical reader. So slowness, as a reflection of careful consideration; and pragmatism, as a reflection of the particular exigencies of a given commission — we work within these parameters.

SCALE: Would you refuse commissions if you did not have enough time to devote to it or if the clients do not follow your ideals?

First impressions are tough to go on. It isn’t always clear what the commission is about, what the ambitions are, how much money there is, even sometimes what exactly the site dimensions are or where it is (!), etc. We have worked on really short-term projects with clients who had a very clear idea, and on interminable projects where the target is constantly shifting. We have had mixed results in both cases.

So really in terms of what the result is – that’s completely a matter of chance – the genie has to show up and whisper the magic incantation. Most of the time she’s lazy! But we show up and hope for an audience nonetheless. Regarding ideals, we usually don’t work on projects where the express agenda is to make a statement. We see architecture as the making of places for well-being – as the backdrop for life.

The firm’s masterplan proposal for Nalanda University is designed as a series of pedestrian routes that link every building and lead directly to a primary street in which the major university activities are located.

SCALE: Did you ever think of practicing in the USA? New York perhaps? Why not, what made you come back to India?

Not really. On a practical level, it is quite difficult to set up a practice in the US – lots of legal/financial implications. But at a more fundamental level, both of us are so much more intuitively connected to Bangalore and India. Our responses come naturally and we always felt like outsiders there. We also had our daughter, Anjali, in the US in 2002 and this really served as the catalyst for our quick return (to capitalize, of course, on the irreplaceable support of family!).

SCALE: How about your life in Dubai? Did you not want to practice in the Middle East?

I had an amazing upbringing in Dubai – 1979 to 1983 (after which I went to boarding school in India). This was a very different Dubai then – just desert beyond the World Trade Centre all the way to Abu Dhabi, wind-swept parking lots where we used to play cricket, Malayalam movies at Al Nasr Cinema, Tikka from Sind Punjab. It all felt provincial, personal, intimate — not at all what it is today. It never did cross our minds to move to the Middle East. In 2003, when we got back to India, Dubai was already well on its way to becoming the playground for the starchitects. There is much to learn from the sophisticated construction and the grand ambition behind so many of these projects but India was home – and for better or worse, we decided on getting back to familiar ground.

SCALE: Tell us more about your first project, the joys, the upheavals, and the learning’s from it?

The brick vault was used to bring down the cost of this 30,000sft. orphanage and community facility that needed to be built at a cost of Rs.500/sft. while being aesthetically appealing, addressing the harsh climate in Trichy, and with generous accommodation for the various uses.

Our first architectural project was the Centre of Hope in Trichy, 200 miles east of Bangalore. This was a project for a client I had worked within the US. It was serendipitous for us to start with this –in many ways the severe budget constraints we worked on here have had a long-term impact on the way we work, approaching our projects with a sense of restraint and pragmatism. Choices are made based on their appropriateness to the task at hand rather than the wilful display of either technique or wealth. Working with two exceptional engineers on Hope, our contractor, M. Manimaran and our construction advisor, R. Rajendran, we were taught how to use the exceptional brick available in the Trichy /Tanjore belt and this choice addressed both cost — spanning most of the upper floors with brick vaults (RCC slabs would have been 40% more expensive), and climate — Trichy is really hot through the year and the brick (with a broken china mosaic cover) offers substantial thermal insulation. Working within tight constraints and learning early on that the most important lessons often come from others, have served us well.

SCALE: What have been the guiding principles in your life in architecture and how do you keep to your ideals in these times and only build what is needed and with materials available? Who are the people you emulate and follow as you keep to your principles?

We are always searching to bring together Louis Kahn’s fundamental binary of Form and Design. Form as a reflection of the nature of the commission — the deep structure — A place to exchange realizations as at IIM Ahmedabad, the inseparability of service and spirituality in the Dominican Motherhouse, the search for spiritual space at the Kimbell Art Gallery, etc. And Design as an expression of circumstance and contingency – responding to the particular context within which one is working – the site, the budgets, the local know-how, etc. This isn’t always possible because of the tight timelines we sometimes have to work with, but one is constantly thinking about Form – the abstract notions of habitation…what is a school, what is a home, what is a public building? And when a commission comes along, we deploy these ideas and start the conversation one must have with the contingencies presented to find common ground. Again, Chipperfield’s wonderful example, of the antagonist and the service provider…Form & Design…Tradition & Circumstance.

“One immediately felt the intimacy of a close familial bond with him, and there seemed to be no persona, no barriers – it was unadulterated, pure, and completely serendipitous. Conversations of rare candour…and this was Doshi.”

“One immediately felt the intimacy of a close familial bond with him, and there seemed to be no persona, no barriers – it was unadulterated, pure, and completely serendipitous. Conversations of rare candour…and this was Doshi.”

I am a regular visitor to IIM Bangalore. It is, in my opinion, Doshi’s (and Vastu Shilpa Consultants’) great masterwork. A project that brings to mind T. S. Eliott’s wonderful essay, Tradition, and the Individual Talent – “…and the historical sense involves a perception, not only of the past-ness of the past, but of its presence; the historical sense compels a man to write not merely with his own generation in his bones, but with a feeling that the whole of the literature […] has a simultaneous existence and composes a simultaneous order. This historical sense, which is a sense of the timeless as well as of the temporal and of the timeless and of the temporal together, is what makes a writer traditional. And it is at the same time what makes a writer most acutely conscious of his place in time, of his own contemporaneity.” It is simultaneously both modern and ancient – of our time and of all time. A place which is as Gaston Bachelard says, “… something that explodes at the centre of our being, releasing to the surface the debris of recognition.”

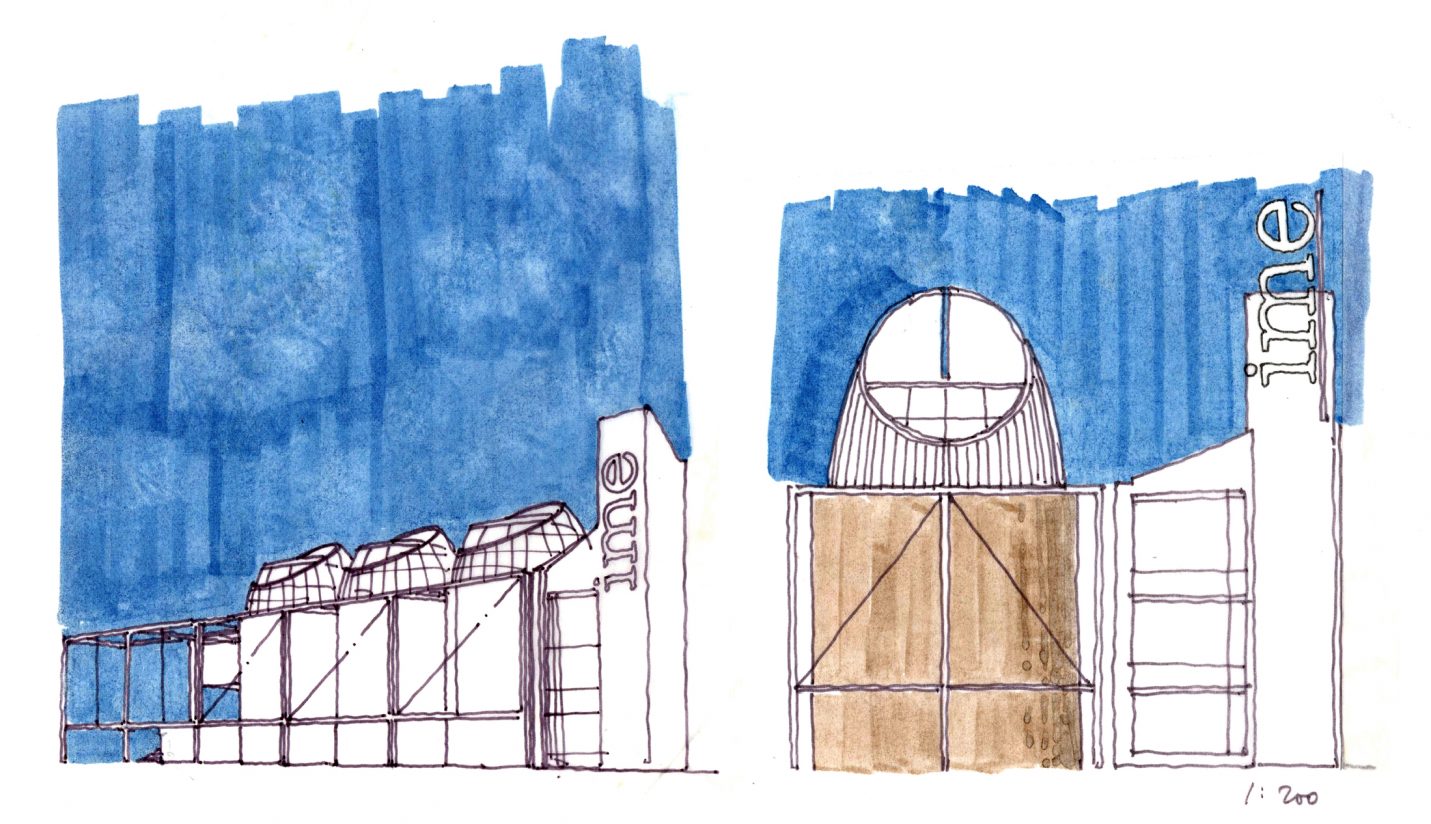

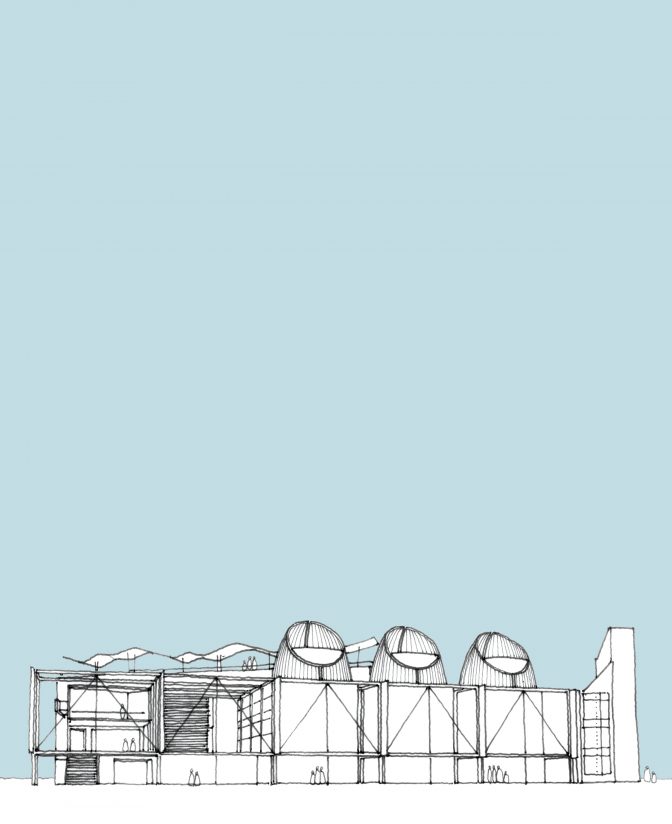

The Indian Music Experience Museum was a project competition submission for which the firm received special mention.

The wonderful thing about Doshi’s practice is that he sees the office as an academic space — a space for engagement and collaboration. His work over these many years has been delightfully inconsistent and this shows both a constantly curious/restless mind, and the influence different collaborators have had on the work. This is a great lesson for us.

SCALE: Which project of yours has been the one that opened doors to recognition for your craft of sustainable designs? Take us through this design of yours.

The Centre of Hope, our very first project was widely published and recognized both nationally and internationally. We went on to do 10 other buildings with Hope Foundation over four years as part of their Tsunami relief work. This was immensely satisfying both professionally and personally.

- The brick vaults considerably reduce the amount of steel used, while giving the structure a distinct aesthetic impact

Other significant projects are:

The eastern facade of the Alila, shows the unobstructed connection between inside and outside. The hotel balconies have timber railings on the east and south sides oriented to views out to Varthur Lake in the south.

1. The Alila, Bangalore hotel & residences, where we worked with Allies and Morrison, thanks to the wonderful patronage of our client, Gautam Nambisan. This collaboration gave us an invaluable insight into the workings of this celebrated practice – the clarity with which they organized programme and their effortless ability to do just enough.

Neev Primary School was conceptualised as a place to exchange realisations under the shade of a large tree.

2. Neev Primary School, where we worked with a sophisticated client, Kavita Gupta Sabharwal, who resonated with Kahn’s idea of the school as a place of exchange. Over 50% of the area was unprogrammed, participatory space, outside the classrooms of varying scales to accommodate both intimate and communal congregation. All of it under a floating fabric roof — figuratively under the shadow of a large Banyan tree.

- Taaqademy is a 1,700 sq.ft. studio for a Bangalore based rock band. The shape of the rooms was important because the normal orthogonal rooms tend to have an echo and bass booms at the corners. The curved exposed brick walls offer an interesting contrast to the rectilinear volume within the building and are substantially visible from the street as almost the whole length of the building facade is glazed.

3. Taaqademy, where our clients, musicians Bruce Lee Mani and Rajiv Rajagopal, and the wonderful sound Engineer, Didier Weiss, taught me how to design an acoustic chamber and together coming up with that unusual organic plan. All choices here based on performance.

4. Bangalore International Centre, taking seven long years to build, this long gestation resulting in a true testament of persistence, collaboration and the search for shared ideals.

SCALE: How do you work as a team? Does Bijoy work on the designs and Sunita on the on-site technicalities? How do you divide your time and work together on projects? Does being married to each other make the process easier or more taxing?

Suni and I mostly work on different projects. She handles many of our interior design projects and sources materials, furniture, furnishings, and accessories for all our projects. I get her to review everything I do. We rarely discuss work at home, and Suni does not have the patience for academic conversations about architecture. Her practical and pragmatic approach is the check I need to ground our work and negotiate contingencies.

Richard Sennett in his essay, The Janus Face of Obsession, comparing houses designed by Ludwig Wittgenstein and Adolf Loos, says, “…in Wittgenstein’s house, obsession has been given full rein and has led to disappointment; on the other, an architect with the same aesthetic but more constraints, more willing to play and to engage in a dialogue between form and materials, produced a home in which he rightly took great pride. A healthy obsession, we could say, interrogates its own driving convictions.” Without Suni, our work would not be enriched by her refined taste and profound empathy. It would lack ‘primordial life’, like Wittgenstein’s house for his sister.

SCALE: Urban Design and Indian Cities. Which city has encapsulated all that you would want a city to look and perform like? If you were to be given the task of designing an Indian City, which city would you want to change and what would you want it to be like? And Why?

What impressions do we carry back of the places we have seen…like Marco Polo, do we have fifty-five metaphors to describe Venice…the city of memories, of dreams, of imagined pasts found on postcards, or simulacrums reflected in the water, of a city of illusions, of bastions, aluminium towers, spiral staircases, and labyrinths. Of these memories, what is of value, and our decrepit cities – aren’t they already like the warm blankets from our childhood – tattered and yet secure, familiar. What would I change? The mayhem on our streets, the cacophonous din of never-ending construction, the distant gaze of strangers, the intolerance of the other, the obliviousness of consumption, the desire to go back to normal, the pontification on offer everywhere. There is something deeply rotten – I am not sure where we can start, but in spite of it all, this is home.

- Bijoy’s lockdown activity.

SCALE: How has the pandemic affected your practice? According to you, will the design world rethink its course in the coming years? What change do you foresee in the world of design and architecture?

I am quite cynical about any fundamental change this pandemic is going to make. It has brought to light, glaringly, the incredible inequities built into the way we construct our buildings. I looked at, for the first time, the labour contract our clients have with the contractors. Approaching it just in terms of common sense and basic humanity, almost all 80 clauses of this agreement were either simply unfair, or ambiguous. And already four states in India have proposed getting rid of even these (less than) basic conditions. In fact, as Yuval Noah Harari said in a recent article, there is a real threat that this crisis may actually be the opportunity nation-states will use to garner more power, increase surveillance, curtail freedoms, etc. It is time to be vigilant

On a personal level, we are struggling without the ability to work closely with our team, reviewing drawings together, discussing, making models, etc. Social distancing and work from home, inherently inhibit the way we work as people. It is incredible to even consider a future where the public congregation is prohibited, both reflecting on our human impulses and our democratic ideals.

SCALE: Take us through your latest project, the Bangalore International Centre, and the design principles behind it. How do you feel about being in the building now with other guests?

We recently completed The Bangalore International Center after an agonising seven-year gestation period. The end result is a reflection of our intense engagement with the clients (Mr. V. Ravichandar, head of the Building Committee), the different people (Harshith Nayak, Kiran Kumar, Nia Puliyel and Rohan Patankar, among others) who worked on this with us, and the patient, committed involvement of our principal contractor, C. Ramesh Babu. Fundamental conditions of how the programme is organised, the formal implications of this, and the experiential qualities, have all evolved because of this engagement.

In 2012, we won a competition to design this privately funded, public institution in the city. The narrow, half-acre site was in a dense residential neighbourhood, in the eastern part of the city. Our competition scheme was predicated on four fundamental questions:

In 2012, we won a competition to design this privately funded, public institution in the city. The narrow, half-acre site was in a dense residential neighbourhood, in the eastern part of the city. Our competition scheme was predicated on four fundamental questions:

1. What is the nature of a Public Building?

2. How does publicness find architectural expression?

3. Given the mixed-use programme, how does one organise this appropriately as a reflection on Louis Kahn’s idea of a ‘society of rooms’? What frame do we use to bring them together in meaningful ways?

4. How do we critically respond to the particular conditions of this commission (the orientation, residential fabric, canal, park, design by committee, etc.)?

The Bangalore International Center is an interconnected series of volumes which has now become the symbol of community, engagement, and dialogue.

BIC opened its doors in February 2019, dramatically different, formally, from the competition scheme. The expression of publicness now an internal one. Spread over the four levels, the meandering, interconnected series of volumes now became the symbol of community, engagement, and dialogue. Across a cascading north-south section one is always aware of connections and inadvertently participating in this idea of communion. Friends commiserate when they see the finished building, but we enjoy this expression of architecture of collaboration, negotiation, and shared ideals. The compressed time spent on the competition forced us to articulate in fundamental terms what this project was about and this helped us keep sight of the larger ambitions of the Institution. The competition scheme set up the normative conditions, ideals and the true nature of things – the Form, as Louis Kahn called it. The realization of these abstract ideals in the built project, incorporating circumstance — the making of architecture, messy, compromised, is the Design. I would like to submit BIC as a valid precedent for the constructive coming together of many people. Though it took seven years to build, the project shows the positive results of this long, intimate, (mostly) positive working environment.

The facility (till recently) has become an active cultural hub in the city, appropriated in wonderful ways by the BIC and the larger community. There is a sense that the building is a real representation of a shared ideal and shared authorship.

The facility (till recently) has become an active cultural hub in the city, appropriated in wonderful ways by the BIC and the larger community. There is a sense that the building is a real representation of a shared ideal and shared authorship.

SCALE: What was the most valuable takeaway from the experience of making the movie with Prof B. V. Doshi. A few words on your experience and about the project. How was it working with your brother?

I look back at the two films my brother, Premjit and I made with Doshi as the most important work I will probably do. It started off as a way to get my brother busy with a ‘project’, and an excuse for us to hang out with Doshi. We spent four months shooting the first film, and it was a wonderful education for both of us. Like Vasudevan Akkitham, his son-in-law, says in the film, we were soon appropriated by Doshi as part of the family. One immediately felt the intimacy of a close familial bond with him, and there seemed to be no persona, no barriers – it was unadulterated, pure, and completely serendipitous. Conversations of rare candour…and this was Doshi. We were lucky to have had this time with him. It brought both of us brothers closer too. Premjit has an incredible ability to discern what is of value, both in terms of experience and aesthetic. He wrote the score for both films, shot, and edited them. They represent his interpretation of Doshi’s work and message. I was fortunate to have gone along for this ride. One of the biggest lessons for us from our time with Doshi is his innate humanity – his ability to connect with people and really engage with them. He never forgets to ask about Sunitha’s mothers’ hip, my mum’s diabetes…He seems to have time for everything and a place in his heart for everyone. I call him the Master of Elastic Time. Being with him inspires us to be better.

1 An architect with whom you would have loved to collaborate

Louis Kahn & Niall McLaughlin

2 One project you wished you had accepted or designed

There are two competitions I was really sad to have lost –

The Nalanda University (with Allies & Morrison) and The Indian Music Experience Museum.

3 One city you want to visit as soon as the pandemic fears subside

I have promised to visit my dear friend Sunil (another Doshi’s office alum) in Pune – to partake of his exquisite filter coffee, Aparna’s incredible Maharashtrian food, reminisce about the good old days, and spend time with little Kimaya, his daughter, reading books and listening to her play the violin.

4 One activity you enjoyed most during lockdown

Drawing and belting Suni’s and Anjali’s amazing dishes.

5 One childhood (architectural) memory.

Growing up in boarding school in the 80s, I remember vividly my summer vacations with my grandparents in Trivandrum and our drives down to Kovalam to visit the beach. These trips almost always included fried fish at the Ashoka and a dip in that amazing pool from where one saw the beaches below and the infinite horizon beyond. This building was my introduction to Mr. Correa and modern Indian Architecture. Unlike anything I had seen before and yet familiar, obvious and in some sense inevitable – a series of terraces on a hill from where to survey the oceans. Moving from the intimate, nestled interior embedded in the rock, a place of refuge; out to the brazen, sun-drenched terrace, a place of prospect. What a beautiful idea!